Ben Jonson famously accused Shakespeare of having “small Latin and less Greek.” But he was exaggerating. Shakespeare was steeped in the classics. Shaped by his grammar school education in Roman literature, history, and rhetoric, he moved to London, a city that modeled itself on ancient Rome. He worked in a theatrical profession that had inherited the conventions and forms of classical drama, and he read deeply in Ovid, Virgil, and Seneca. In a book of extraordinary range, acclaimed literary critic and biographer Jonathan Bate, one of the world’s leading authorities on Shakespeare, offers groundbreaking insights into how, perhaps more than any other influence, the classics made Shakespeare the writer he became.

Is Shakespeare on par with the ancient Greek and Roman writers of the classics? What made him stand out, rather than his contemporaries?

JB: Astonishingly, considering that the theatre was still a fairly disreputable profession in Shakespeare’s time, people began comparing his works to those of classical antiquity even in his lifetime. His poems were compared to those of Ovid, his comedies to Plautus and his tragedies to Seneca. A few years after his death, his fellow-dramatist Ben Jonson wrote a poem in his memory—it’s included in the First Folio—in which he claimed that Shakespeare’s plays actually surpassed those of the ancients. Given that Jonson himself was phenomenally learned in the classics, that was a striking claim indeed. It does immediately provoke the question: why has Shakespeare and not Jonson or any of the other fine dramatists of the Elizabethan age become our classic, the modern equivalent of Sophocles or Virgil? That’s a question I’ve explored in my earlier books on the history of Shakespeare’s posthumous reputation—I return to it in the final chapter of this book, where I look at the classical idea of “fame”—but the implicit answer I have found, in the several years it took to research and write How the Classics made Shakespeare, is that the sheer range of his work was unmatched by any contemporary. Jonson was more obviously compared to Horace, Spenser to Virgil and Bacon to Cicero, but Shakespeare seemed to combine the gifts of them all. Similarly, Marlowe was great in tragedy and Jonson in comedy, but Shakespeare was, as he wittily puts it himself in Hamlet, the master of every genre, “tragical-comical-historical-pastoral.”

How important was it that Shakespeare’s audiences understand allusions to fables and myths? Did Elizabethan theatre-goers have greater cultural literacy than modern audiences at Shakespeare plays when it came to understanding these references?

JB: This is a big theme—and an anxiety—in my book. You have to remember that Latin was the absolute core of the Elizabethan schoolroom curriculum. Grammar school meant Latin grammar, morning, noon and night. The history, literature, thought and culture of ancient Rome—and, to a lesser extent, Greece—was everywhere in education, in the Elizabethan frame of mind, even, I suggest, in the architecture and iconography of the city of London. The theatres themselves were designed on Roman models. This meant that anyone who was literate, and probably quite a few citizens who were not, would have known what Shakespeare was talking about when one of his characters mentioned Hercules or Julius Caesar or Lucrece or Adonis or Actaeon or Alcibiades and a hundred others. My anxiety is that with the decline in knowledge of classical literature, history and mythology, many such references now pass over the heads of playgoers and students. For example, I have a riff in the book that begins with an inscription on a funeral monument in a London church in the parish where Shakespeare lived and then goes into a reference to Jason and the Golden Fleece in The Merchant of Venice. Both the monument maker and the playwright clearly assumed that people would know that story—but not many of us know it now (though maybe it is handy that Disney has reanimated some of the old classical myths!).

In the book, you say that Shakespeare and his fellow playwrights agreed that “a work was good not because it was original, but because it resembled an admired classical exemplar.” If there are only 7 basic plots under the sun, why do modern audiences and writers frown upon stories that aren’t “original” while also still appreciating Shakespeare for his ability to pay homage to the classics?

JB: I like to tell my students that they need to get the nineteenth-century Romantic idea of genius and originality out of their head when they think about how Shakespeare put his plays together. It’s better to find an analogy in the way that art students were trained for centuries: you begin by copying the works of the great masters—that is how you hone your technique— and then you start performing variations on classical themes. That is how you prove your ingenuity: by variation and embellishment, not starting with a blank canvas. My book grew from a series of lectures at the Warburg Institute in London: it was the Warburg scholars, such as E. H. Gombrich in whose memory the lectures were named, who did more than anyone else to help us to understand this Renaissance process of offering original re-presentations that engage in dialogue with what they called “the classical tradition.”

Plenty of people have accused Shakespeare of plagiarism, or of lacking sufficient training in Greek and Latin. What are some other common misconceptions about Shakespeare that you’d like to rebut?

JB: These claims go back to Shakespeare’s own time and to the indignation of university-educated dramatists, such as Robert Greene (who called Shakespeare an “upstart crow”), upon witnessing the rapid rise to theatrical prominence of the man from the backwoods with only a grammar school education to his name. But we need to remember that the grammar school in Stratford-upon-Avon produced some real talent—one of the schoolmasters was a published author of Latin verse, while Shakespeare’s fellow pupil Richard Field became a distinguished printer of books in many languages. The danger of the misconception created by jealous writers such as Greene is that it leads all too easily to the idea that Shakespeare couldn’t have been educated enough to write the plays … and that leads to all those ridiculous authorship conspiracy theories. The classical learning in the plays precisely matches that of the grammar school curriculum, with some later reading added on (notably the English translations of Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans). The poems and plays are emphatically not written in the very different styles that we find among university-educated dramatists, Inns of Court trained lawyers, let alone aristocrats.

Is there any classic tale that Shakespeare reimagined that has made a lasting impression on you?

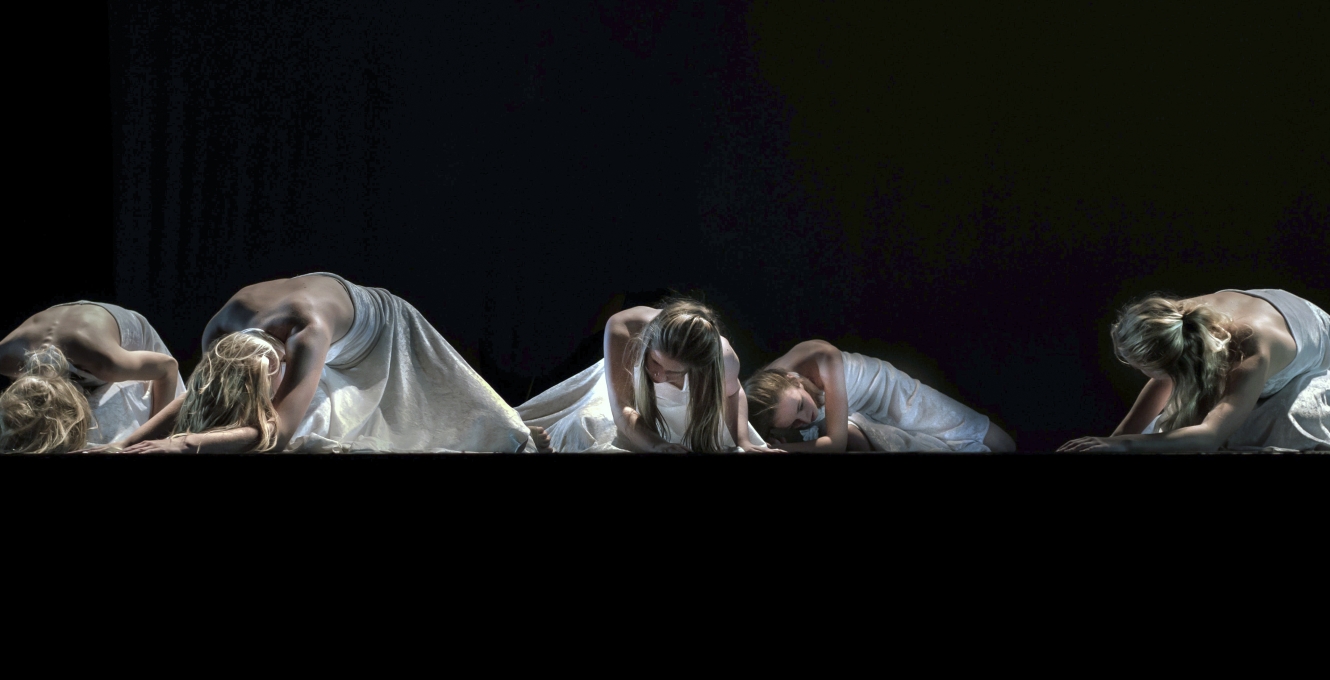

JB: I guess the one that has most haunted me is his adaptation of Ovid’s story of how the artist Pygmalion made a statue of a woman that was so beautiful that he fell in love with it and the gods then brought it to life. That’s an allegory of the power of aesthetic delight and a very sexy story, but also a slightly seedy one in which the woman is merely the object of desire. What is beautiful about Shakespeare’s reimagining is that the statue is not some abstract notion of female beauty, but a once and once again beloved wife who has been abused by unfounded male sexual jealousy and is then given back, so that the husband has a second chance—I’m talking, of course, about Hermione and Leontes in The Winter’s Tale, where the reanimation at the end is an allegory of the power of theatrical magic (achieved through distinctively female agency in the form of Paulina) and at the same time a triumph of love as opposed to an act of sexual desire. The whole question of eros and its relation to theatre and to magic is at the heart of my book.

In your opinion, are there any writers from the past century who drew upon the classics and/or Shakespearean plots and might stand the test of time like Shakespeare still does today?

JB: There was no guarantee that it would be Shakespeare rather than some other dramatist who became our immortal, and by the same account it would be a fool’s game to guess who will and who will not endure from the last hundred years. What does strike me, though, is that the poets whom I find myself reading—as Ben Jonson said we should read Shakespeare—“again and again” all seem to have been steeped in the classics, fascinated by the old stories and adept at translating, imitating and remaking them. I am thinking, for example, of W. B. Yeats, Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, Ted Hughes and Seamus Heaney. They were the poets who, along with Shakespeare, were my first “classics” when I was a teenager and a student.

Jonathan Bate is Provost of Worcester College and professor of English literature at the University of Oxford and Gresham Professor of Rhetoric at Gresham College. His many books include Soul of the Age: A Biography of the Mind of William Shakespeare and an award-winning biography of Ted Hughes. He broadcasts regularly for the BBC, has been on the board of the Royal Shakespeare Company, is the coeditor of The RSC Shakespeare: Complete Works.