The further the American Revolution recedes into history, the easier it is to miss just how close the United States of America came to be a divided collection of competing colonies under the punishing heel of an angry Britain. The nation’s founders had first dared to declare their king a despot and then to challenge the most powerful army in the world to a war over turf. The odds of success seemed impossibly small, even if the red coats of the British troops made them conspicuous targets on the battlefield. A seven-year campaign, much bravery, a bit of luck, and the timely help of the French produced an unlikely victory. In September 1783, the promise of the Declaration finally led to the reality of independence.

But along with the triumph came a wrenching setback: the new nation’s original plan to govern itself, the Articles of Confederation, simply failed to work. The states had been determined to prevent the new national sovereign from trampling on their liberty—having defeated the king, the last thing they wanted was another one—so the Articles intentionally created a very weak government. In their eagerness to prevent tyranny, its drafters overdid it. They created a United States of America not united enough to protect itself or its commerce. If the republic was to endure, this collection of divided states needed to be rescued from the fatal flaws of the Articles.

So, in 1787, the nation’s leaders gathered in Independence Hall in Philadelphia to draft a new governing constitution. It was the same building where many of them had boldly voted to declare independence from Britain in 1776 and where they had drafted the Articles of Confederation in 1781. This time they knew they needed a more detailed constitution and a stronger national government. And they also knew they needed all the help they could get.

The founders struggled with a dilemma, one that has repeated itself many times since. The leaders of the states jealously guarded the separate identities that had emerged through the colonial times. They were proud, of course, of the new nation, but many were even prouder of the rich traditions of their own states. After all, the nation’s short eleven-year history was a brief blip compared with the century and a half during which many of the colonies had prospered—and none of the proud states wanted to surrender their own interests to a new national identity. The agriculturally oriented South fiercely opposed having Northern merchants dictate policy, and the settlers who pushed west didn’t want the big cities controlling their lives. Residents of small towns were always fearful of the reach of the large cities. The Articles of Confederation were so weak because the states were so strong, and state leaders wanted to keep it that way.

But the devotion to state power almost immediately clashed with the requirements of the new country. European powers coveted the vast, untapped wealth of the new continent. Tensions among the states threatened budding commerce, and the new nation lacked the most basic structures for making decisions. Even before Maryland became the last state to ratify the Articles in 1781, the document was obsolete.

So when the founders returned to Philadelphia in 1878 to draft the new constitution, they faced a profound dilemma. They needed to build a stronger national government without interfering with the states’ expectations that they would keep their identities and their power. No other new nation had ever attempted to have its constituent parts create a strong national government without those parts deconstituting themselves in the process. The solution they came up with was federalism, American style. It had the great virtue of winning political support from the states, by maintaining their identity. It had the great challenge of creating a new ship of state, which had to navigate especially fierce and opposing currents. American federalism, in fact, has always been much less a fixed structure than a set of rules of combat. In the centuries since, the underlying tension between national unity and state power has never gone away. Neither have the great political battles that federalism precipitates.

That challenge has become both what defines the operating reality of American government and what differentiates American government from governments in the rest of the world. It is the field of battle on which the most important American political struggles have been fought. Through the years, these struggles have sometimes threatened the very principles that brought the founders to Philadelphia the first time to declare independence from the king.

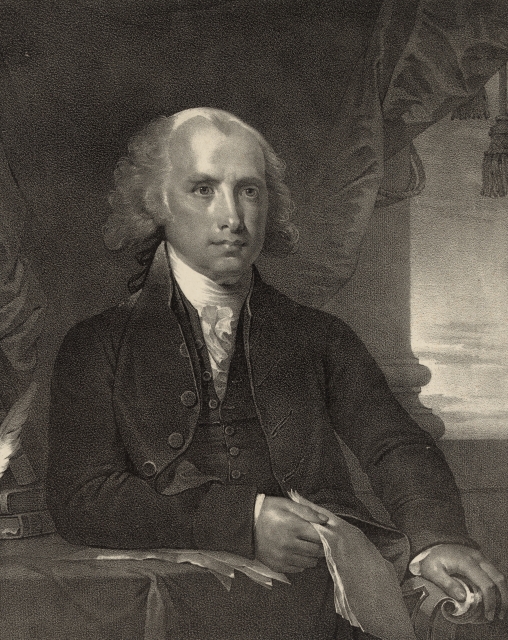

When the founders met in 1787 to write the new constitution, James Madison led the debate. He was much younger than most of his colleagues, and he had a true genius for finding the bridge between opposing factions. As Joseph J. Ellis put it, Madison was “the acknowledged master of the inoffensive argument that just happened, time after time, to prove decisive.” Madison “lived in the details,” Ellis explained, “and worked his magic . . . with a more deft tactical proficiency than anyone else.”1

His tactical brilliance, in fact, helped him cobble together the two greatest institutional inventions of the founders: separation of powers between executive, legislative, and judicial branches, which prevented the country’s new president from becoming too kinglike; and federalism, which delicately balanced the powers of the national government with those of the states. Madison is perhaps best known for the first invention, but his second invention was the truly essential one, for without a plan to deal with the power of the states, the country could well have become fatally fragmented—and easy pickings for British, French, and Spanish governments eager to expand their power in the Americas. The invention of federalism allocated power between the federal government and the states in a way that gave the federal government enough strength to keep the country intact and accomplish national goals without making it so strong as to interfere with the self-government of the state and local governments. That was no mean feat.

(A quick aside: There’s often much confusion around the terms “federal” and “federalism.” In a formal sense, “federal” refers to a system of government in which power is allocated between the national government and its components, like the states. But in the United States, by long tradition, the national government is also referred to as the “federal government,” so to keep with common usage, I’ll use “federal” throughout the book to refer to the government run from the national capital. “Federalism” will refer to the American strategy for dividing power between the national government and the states.)

After they had drafted the Constitution, the founders knew just how fragile a system they had cobbled together. As they left Independence Hall on the last day of the constitutional deliberations, a lady is reputed to have asked Benjamin Franklin, “Well, Doctor, what have we got—a Republic or a Monarchy?” Franklin’s reply: “A Republic, if you can keep it.”2 Keeping it ultimately depended on whether Madison’s two great inventions worked. For more than two centuries, they did, if sometimes only barely, surviving partisan conflict, a civil war, and the rise and fall of multiple political parties. In the twenty-first century, however, the two institutions have become increasingly rickety, and so did the challenge of keeping the Constitution.

This essay is an excerpt from The Divided States of America: Why Federalism Doesn’t Work by Donald F. Kettl.

Donald F. Kettl is professor emeritus and former dean of the School of Public Policy at the University of Maryland. Until his retirement, he was the Sid Richardson Professor at the LBJ School at the University of Texas at Austin. His books include Can Governments Earn Our Trust? and Escaping Jurassic Government. Twitter @donkettl

Notes

1. Joseph J. Ellis, Founding Brothers: The Revolutionary Generation (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001), 53, 113.

2. Notes of Dr. James McHenry, a Maryland delegate, published in The Records of the Federal Convention of 1787, vol. 3, ed. Max Farrand (1911; reprint, 1934); see Bartleby.com, no. 1593, https://www.bartleby.com/73/1593.html.