To an earthbound species like humans, bird migration is nothing short of extreme. A four-ounce Arctic tern can fly to Antarctica and back each year during a lifetime that spans 30 years. Bar-tailed godwits can fly from Alaska to New Zealand in a single nonstop flight that lasts eight days. And hundreds of other species ranging from hawks to hummingbirds routinely perform their own epic migrations.

Extreme as it may seem to a terrestrial primate like us, migration is for many birds a common-sense reaction to the availability of resources. After all, seasonal change is one of the most dependable features of our planet, providing predictable resources such as spring leaf-out, monsoon rains, insect hatches, and fruiting seasons. Migrating birds are just following that abundance.

How migration might have evolved, via gradual steps, is a tougher question. One leading theory holds that birds started by making small annual movements as they searched for an edge in feeding or nesting opportunities. Individuals whose movements gave them better chances to survive and reproduce passed that migratory behavior along to their offspring. What at one time might have been a short jaunt to and from a seasonal feeding ground might over time have become exaggerated as climates or resources changed.

A key force in this evolution may have been the earth’s many cycles of environmental change, including, over the last 2.5 million years, more than 20 glacial cycles leading up to the most recent melting and retreat of vast ice sheets about 15,000 years ago. One can imagine that, with every cycle of Pleistocene glaciation, migrants retreated to southern breeding localities and made shorter migrations while the ice ruled the north. Then, when the ice receded, the migrants moved north to take advantage of breeding opportunities in the unoccupied habitat that emerged.

The Continuing Evolution of Migration

In some birds, it’s possible to still see the imprint of past evolutionary forces in their present-day migrations. The northern wheatear—a perky brown songbird with a flashy black-and-white tail—breeds in arctic tundra around the Northern Hemisphere. It was originally a Eurasian species, but as ice sheets began to recede around 20,000 years ago, the species colonized North America. Colonists came from both directions: from Siberia eastward into Alaska, and from Europe westward across the Atlantic and into Canada.

Amazingly, none of these wheatears have started spending their winters in the Americas. They all still retrace their ancestral migratory paths to wintering grounds in Africa. Wheatears in Alaska head westward across Asia to East Africa, a route covering 8,700 miles—the longest distance known for any migratory songbird. Meanwhile, wheatears that nest in arctic Canada get to Africa from the opposite direction, migrating eastward across the Atlantic. It’s one extreme example of the way migration probably evolved for many species: a gradual increase in distance between summer and winter grounds, while the instinct to migrate and the migratory path remain relatively unchanged.

The Galapagos hawk is another example of past evolutionary changes made visible. It’s the only hawk endemic to the Galapagos Islands, 600 miles away from the South American mainland. How it got there has been a mystery, since most raptors avoid flying over open water. But genetic evidence now shows the Galapagos hawk is an evolutionary offshoot of the Swainson’s hawk, an elegant species of North American prairies whose migration takes it to southern South America. It’s now thought that the hawks’ ancestors were undertaking this same migration about 300,000 years ago when a flock went off course, ended up in the Galapagos, and became the founding population of a new species.

But there’s a catch. Before evolution could produce any Galapagos hawks, those first off-course birds would have had to somehow lose their inclination to migrate away from their newfound islands. Exactly how and why birds become “migration dropouts” is still a puzzle, but scientists have seen it happen in several species. For example, in 1980 ornithologists in Argentina discovered six pairs of barn swallows nesting under a bridge in Buenos Aires province. This familiar swallow of North American fields and farms migrates to South America every year, but this was the first time it had ever been known to breed there.

And it wasn’t an isolated mistake. In less than four decades, the population grew to thousands of pairs. In order to breed successfully in Argentina, these barn swallows have somehow been able to skip their northward migration and shift their breeding season by six months to match South American seasons. A similar suite of life-history changes has been seen in dark-eyed juncos (colorful sparrows that often visit feeders across North America) that started skipping migration and nesting in San Diego in the 1980s.

Migration and Climate Change

Changes to earth’s climate may have helped push the evolution of bird migration along, but today the changes brought about by the burning of fossil fuels are testing birds’ ability to keep up. As temperatures warm up earlier in the year, plants leaf out and flower earlier, and insects emerge earlier. Migratory birds face the possibility of arriving back “home” only to find that plants and insects are either not ready yet or have already peaked, a situation known as ecological mismatch.

One of the best-studied ecological mismatches involves the European pied flycatcher. In recent years these migrants have responded to a warming climate by breeding earlier—but unfortunately the key insects they feed to their chicks have advanced their calendars even more. The result is that the spring insect flush has already peaked by the time the flycatchers have chicks to feed.

In a hopeful twist, research is showing that pied flycatchers may have some flexibility in how they adjust their annual cycle. It was long thought that their migration schedules and breeding timing were essentially fixed. But research suggests that the birds can do some fine-tuning thanks to their physiology. While still in the nest, young pied flycatchers seem to calibrate their biological clocks using day length before making their first fall migration—and this helps set them up for an earlier return the next spring.

The case of the European pied flycatcher points up a paradox for all birds. Migration is a powerful way to turn seasonal variation into an advantage, capitalizing on resources while they’re fleetingly abundant. But migration is also an exhausting and uncertain undertaking that renders birds vulnerable to adverse conditions throughout their annual journey. Nevertheless, judging by the thousands of species that have evolved to migrate, it’s a gamble that tends to pay off.

With the Right Field Guide, Migration Can Even Help with Bird ID

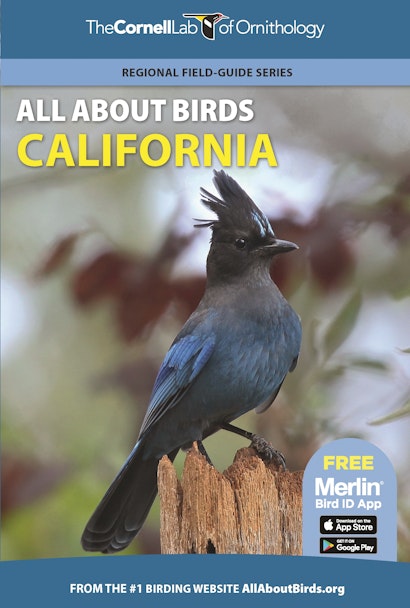

In the birdwatcher’s eternal quest to put names to the birds they see, perhaps the most consistently overlooked clue is a bird’s range and migratory behavior. That’s why birders should always check the range maps in their field guide before making an identification. And it’s one big advantage to the regional field guides in Princeton University Press’s All About Birds series (prepared by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and named for their popular website).

Identifying birds quickly and correctly is all about probability, and regional field guides give birdwatchers a head start by providing a shortened list of likely species. By displaying migratory patterns, the range maps in these guides go one step farther. Red-tailed, rough-legged, and Swainson’s hawks can look pretty similar. But a birder in Tucson could use the Southwest regional guide to know that Swainson’s are only present in summer, rough-legged only in winter, and red-tailed year-round.

Staring down a sparrow with a rusty crown, a birder in Cleveland could use the Northeast regional guide to know that Chipping Sparrows are expected in summer, but they get replaced by American Tree Sparrows in winter.

Many of summer’s birds, including most of the warblers, flycatchers, thrushes, and hummingbirds, leave their nesting grounds as fall approaches. Other birds move in to replace them, and this mass exodus and arrival is part of what makes birdwatching so exciting. Paying attention to range maps and migration timing is one of the best-kept secrets for having more success—and more fun—while watching birds.

This AllAboutBirds.org article was adapted from the third edition of the Handbook of Bird Biology, edited by Irby J. Lovette and John W. Fitzpatrick and published by John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. and Cornell Lab of Ornithology.