In 1366, a group of medieval women who worked in the silk trade in London formed a union to protest against price-fixing. Twenty years later, Matilda Pence ran her late husband’s skinning business, employed apprentices, and left a bequest to a female scribe called Petronella. In the early fifteenth century, a serving woman accompanied her mistress, the writer and mystic Margery Kempe, on pilgrimage to Europe and the Holy Land, abandoned her employer, and gained a lucrative new position looking after wine and provisions for a large guest house in Rome. Later in the century, an English duchess, Katherine Neville, married a teenager when she was sixty-five.

Medieval women led varied, interesting, risky lives. They worked in a wide variety of jobs, were economically active, and were often independent. After the Black Death–the worst pandemic the world has ever known–swept across Europe in the middle of the fourteenth century, opportunities increased for survivors. In England, wages went up and more women moved to towns and entered the paid workforce. Indeed, the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries have been termed a ‘golden age’ for women and were a crucible for women’s rights. Inheritance laws in England enabled widows to keep property and wealth, and many women were active in business. Widows often married several times, and continued to control businesses and investments.

This is the world in which Chaucer’s Wife of Bath–one of the most famous and enduring female characters in English literature–was born. Alison of Bath is an unprecedented figure. Before this point, women in literature tended to be princesses, damsels in distress, queens, virgins, or nuns–or witches, old crones, whores, or bawds. One of the things that makes the Wife of Bath extraordinary is that she is ordinary–she works, has sex, gets married, travels, gossips with her friends, makes mistakes. She also, like many ordinary women, suffers domestic abuse, and she tells a story about rape.

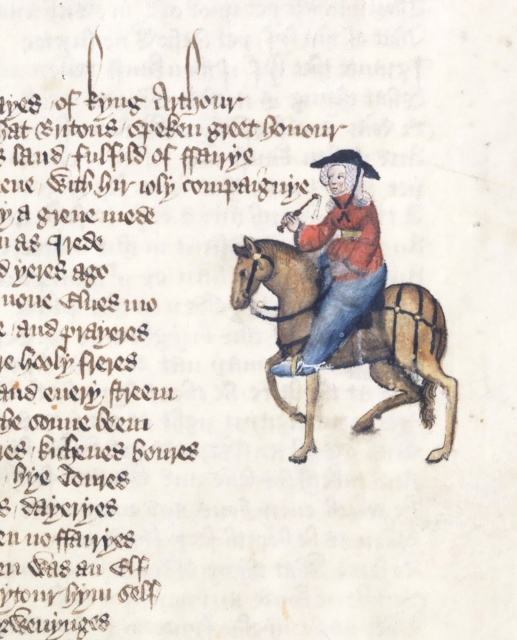

While she is larger than life–travelling three times to Jerusalem, marrying five times, talking for far longer about herself than any other character in the Canterbury Tales does–she is also ‘realistic’ in some ways. Many readers identify with aspects of her, and are moved by the power of her voice and personality. With the Wife of Bath, Chaucer embarked on new experiments with literary character. This woman–who would not have had a voice at all in other medieval texts–is given a more developed interiority than any other character (male or female) in medieval literature. She is embedded in temporality and tells us about her memories and her hopes for the future; she has an ethical sense; she has a strong sense of humour; she understands her own faults and errors; she is clever and witty.

Above all, the Wife of Bath knows that she herself has been formed from a misogynist canon and that she embodies many of the faults that antifeminists deplored (she drinks too much! she tells her husband’s secrets to her friends! she manipulates men! she eyes up the men at her husband’s funeral!). When she asks ‘Who painted the lion?’ she is reminding readers that what art reveals is determined by the prejudices and position of the artist. She emphasises to her listeners that all the stories have been told by men, and that if women had had the chance to give their side of the story, books would be full of tales of the wickedness of men–rather than the wickedness of women.

Chaucer did something entirely new when he created this figure. The Wife of Bath’s main source (La Vielle from Le Roman de la Rose) is a cynical old bawd. Chaucer transformed this figure into an essentially respectable, much-married woman, a woman who is funny and self-aware. Crucially, she is a woman who is economically independent, and who has both worked (in the cloth trade) and has benefitted from medieval England’s inheritance laws. When she tells the story of her marriages, it is an economic story. She made a terrible mistake when she surrendered land and wealth to her fifth husband, and could only regain control over her life once she regained economic control. As Virginia Woolf was to argue many hundreds of years later, women need economic independence–a room of their own–to be able to have control over other aspects of their lives. Although women in fourteenth-century northern Europe were by no means in a position of equality with men, they were living at a moment of increased possibilities. The first ordinary woman in English literature is very much a product of this fascinating historical moment.

As soon as Chaucer wrote this character, readers recognised her as exceptional, and as different from other characters. What she embodies, and what she says about women, have caused outrage and anxiety across time. Indeed, the Wife of Bath provoked extreme and detailed responses even in the earliest manuscripts–in which scribes argue with her, contradict her, and tell readers not to take her seriously.

Tracing her afterlife across time reveals a fascinating duality. Many male readers were horrified and appalled by her, and made elaborate and exhaustive attempts to silence her, to tame her voice, or to condemn her. These attempts range from burning ballads about her in the seventeenth century, to Pope writing a version of her in the eighteenth century that removes all the references to sex and the body; from an American play in the early twentieth century that punishes her by making her marry the Miller, to Pasolini’s film in the 1970s that portrays sex with her as causing men to die.

At the same time, readers could not leave her alone. She has obsessed audiences in a way that few other literary characters have. In the fifteenth century, when John Skelton described the Canterbury Tales, he summed up the whole of the rest of the text in four lines, before devoting ten to the Wife of Bath. When her tale reached France it was translated by Voltaire, and then adapted into an extraordinary stage spectacular that was staged all over Europe. We can see her influence in works by Shakespeare, Dryden, and James Joyce.

More recently, the Wife of Bath has been reimagined by contemporary women writers, including Black British writers such as Jean ‘Binta’ Breeze, Patience Agbabi, and Zadie Smith. In Smith’s Wife of Willesden, Alison becomes Alvita, a contemporary woman from North-West London, with Caribbean heritage. The Book of Wicked Wives with which her husband torments her–in Chaucer’s text, a compendium of misogynist texts by writers such as Jerome and Matheolus–becomes a selection of books such as Jordan Peterson’s Twelve Rules for Life and Warren Farrell’s The Myth of Male Power.

Indeed, many aspects of Smith’s adaptation remind us that the structures that oppressed medieval women have not been dismantled today. Domestic abuse, rape, the dominance of male voices in textual culture, the invisibility of older women in public life are all issues with which we are only too familiar. The power of Alison’s voice, however, and the fact that that voice cannot be silenced–even when printers were imprisoned for publishing ballads about her–tells another story. Many medieval women did manage to hang onto their inheritance, to carve out interesting lives for themselves, to find ways to voice their own stories. The Wife of Bath has remained a recognisable, influential character–popping up in texts by authors as varied as Ted Hughes, John Gay, and Hilary Mantel. She speaks to our contemporary moment in myriad ways–and there are many lessons that we can learn about past and present, life and literature, from this unique figure.

The Wife of Bath has taken many knocks over the years. She has been mutilated, misrepresented, mocked, and mansplained. Nevertheless, she has persisted.

Marion Turner is the J.R.R. Tolkien Professor of English Literature and Language at the University of Oxford, where she is a Professorial Fellow of Lady Margaret Hall. Her books include the prize-winning biography Chaucer: A European Life.