It is an unspoken assumption of our culture that seriousness should be sober-faced and that playfulness cannot really be serious. This assumption has led many readers and quite a few critics as well to imagine that Nabokov, whether one finds him entertaining or annoying, is not finally a serious writer. He, for his part, accustomed as he was to peremptorily dismiss writers of whom he did not approve, zestfully cast into the dustbin of literature such novelists as Thomas Mann, Joseph Conrad, and Albert Camus, who, at least as he saw them, made fiction a vehicle for the grimly insistent enunciation of philosophical or moral views.

The element of play is conspicuous in all Nabokov’s novels. They abound in anagrams, word games, ingenious literary allusions, clever ironies, and intricate networks of recurring motifs. All these certainly constitute the lively texture of Nabokov’s fiction, and critics have been justified in tracing its elaborate patterning and through their guidance inviting readers to join in the inventive games Nabokov plays. For at least some, the games are evidence of a coy, self-regarding writer whose horizons do not extend beyond his own work and the larger context of antecedent in literature in which that work is conceived.

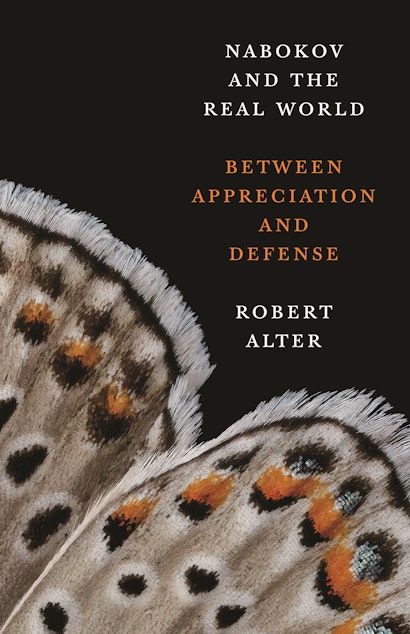

The playfulness, very often enacted through gorgeous prose, is surely essential to the delight of reading Pnin, Pale Fire, or even Lolita. Attention to ingenious play and to the sheer wit of the writing is thus quite often brought to bear in Nabokov and the Real World. But what these considerations of his major books variously argue is that the playfulness is finally a means to make us understand more deeply and more subtly a whole range of moral, emotional, and political challenges that may confront us in the consequential realm beyond words and books and writers. The historical upheavals of the 20th century powerfully and painfully impinged on Nabokov. The Bolshevik Revolution compelled him to flee his native Russia before he reached the age of twenty, and some of the people to whom he had been close ended up in the Gulag or facing a firing squad. After barely a decade in Berlin, where he had settled among many other Russian émigrés, a different kind of murderous dictatorship obtained power, and so a second flight, to Paris, became necessary. Then, after the Nazi occupation of France in 1939, Nabokov underwent still a third forced displacement, though it would prove a happy one, to the United States. He had begun writing in English, no doubt with an eye to imminent flight, in the later 1930s, and he was subsequently proud to call himself an American writer.

With this background of wrenching experience, Nabokov’s fiction was more often political than has been generally realized. He devoted two novels to the scathing representation of the horrors inflicted by totalitarian states, the first, Invitation to a Beheading, in Russian, and the second, Bend Sinister, in English. But the specter of totalitarianism flits through others of his novels. Loss is a very frequent presence in his writing—loss of homeland, loss of those who perished in the vicissitudes of history, and a person’s loss of a beloved. Love, in fact, is something Nabokov profoundly cared about, and quite a few of his plots focus on both the pain and the exaltation of passionate love. Much as some would be loath to see this in a novel centered on a repugnant form of sexual perversion, that is essentially what Lolita is about. Art is a primary value in Nabokov’s view of the human world, but his fiction repeatedly shows how art itself can be perverted, how a devotion to a fake simulacrum of art can lead to the infliction pain and harm on others.

A rather common response to Nabokov has entailed complaints that he is altogether too cerebral or calculating a writer. Nabokov and the Real World seeks to demonstrate in a series of close readings of his books that in fact they are permeated with keenly felt emotion. Dickens was one of his chief literary enthusiasms. It is not surprising that he should appreciate the proliferation in Dickens of brilliantly inventive metaphors, for he, too, delighted in the use of metaphor. It may be a little more surprising that he should value Dickens for the compassion exhibited in his novels—“the real thing, keen, subtle, specialized compassion, with a grading and merging of melting shades, with the very accent of profound pity in the words uttered.” It is what his own fiction at its best also does, the instrument of playfulness carrying us into what deeply matters in the real world.

Robert Alter is professor of the Graduate School and emeritus professor of Hebrew and comparative literature at the University of California, Berkeley. His many books include The Pleasures of Reading in an Ideological Age, Imagined Cities: Urban Experience and the Language of the Novel, and Pen of Iron: American Prose and the King James Bible (Princeton). He lives in Berkeley, California.