“A sense of incredulity that one should be anyone in particular, a specific individual of a particular species existing at a particular time and place in the universe.”

Thomas Nagel

Last week I was about to enter a coffee shop in Berkeley, when a person came rushing out, mask-less and shouting. For a second I thought I could see her voice, showering the insidious droplets I have learned too much about. “You’re all being bamboozled,” she yelled at the threshold, to no one in particular.

How to respond to her? I didn’t want to end up in a shouting match, and I was frightened to move any closer. I realized that most of my arsenal of communication lived in my facial expressions. Fear, confusion, scorn—I tried them all on, but the face mask I was wearing rendered each affect useless. I stood there ten feet away, nerves searing but outwardly expressionless, myself and not myself.

“Move your foot or hand an inch; slip your hold at all; and your identity comes back in horror.”

Herman Melville

In these strange months, masks have become a symbol of care—the best we can do in day-to-day public life to mediate against the threat posed by our speech organs. I have been thinking about the role of literal masks in our culture in relation to the kinds of figurative masks, or personae, which lie behind the construction of poems.

Unlike Americans, the poets I love have been quick to put on masks, seizing on the freedom that comes with a temporary escape from, or expansion of, the self. As Hart Crane wrote, “I dreamed that all men dropped their names and sang.” We know about the great persona poems in modern English, from Robert Browning to Elizabeth Bishop to Robert Hayden, pieces where the poet intentionally assumes another’s voice, whether an Italian duke, Robinson Crusoe returned to England, or a visitor to planet Earth.

But the relationship between personae and poetry runs deeper than a particular genre of poem. Masks abound across classical Chinese poetry and ancient Greek and Latin poetry and drama. For many poets, the possibility of temporarily exceeding or expunging one’s personality gets to the heart of the creative impulse. In one of his vilest invectives, Catullus rages against two colleagues, Furius and Aurelius. Their mistake? They “have dared deduce me from my poems.”

“Je est un autre (I is somebody else).”

Arthur Rimbaud

To take this line of thinking further, I’ve sometimes felt that the pressure exacted upon thought and feeling in a successful lyric means that every such poem could be considered a persona poem. The transformative task of handling language at its most dynamic grants the poet access to some emotion, paradox, or way of seeing that was previously unfamiliar. Whether for Sappho or Thomas Wyatt or Rickey Laurentiis, a poem (at least temporarily) leaves its maker a different person than when they began, which explains why poets often describe a sense of estrangement when looking back on their own work.

Rather than an outsize personality, or even a strong subject matter, a chameleon-like susceptibility to transformation might prove the most enduringly useful quality for a poet. In this regard, John Keats’ radical notion that “a poet is the most unpoetical of anything in existence because [they have] no Identity; [they are] continually in for and filling some other body” makes sense, at least in the act of writing.

“To consent to being anonymous… is to bear witness to the truth. But how is this compatible with social life and its labels?”

Simone Weil

But the literary “filling” of “some other body” can also cause damage. Some authors have played fast and loose with identity, to everyone’s detriment. In fiction, Toni Morrison has detailed how Black characters in novels by white authors often lack complexity, reinforcing the narratives’ dominant epistemologies even when intended to disrupt them. The all-encompassing self that Walt Whitman constructs as his persona in Leaves of Grass—“I am the poet of slaves and of masters of slaves”—can end up sounding, ironically, just like a mid-19th century racist white man.

“Most of all beware, even in thought, of assuming the sterile attitude of the spectator, for life is not a spectacle.”

Aimé Césaire

In my other job (speaking of masks!) as a Congregational minister, I’ve been embarrassed by my temporary inability to recognize my congregants who are wearing face masks when I run into them in town or outside our church. Several times, I’ve had to pause (about the length of time it takes to read a short poem, perhaps) before I can greet them accurately.

With the gift of their voice, or a distinctive physical movement, something clicks. My mind fills in the features behind their mask. The name comes back. And the person is dearer to me for having been placed at a temporary distance.

“Almost anyone under the circumstances would have doubted if [the letter] were theirs, or indeed if they were themself.”

Emily Dickinson

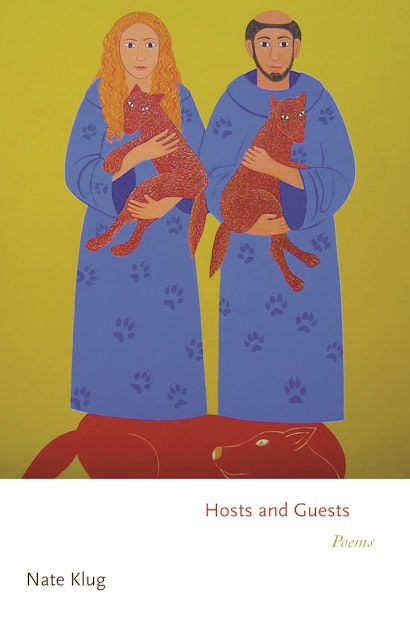

Hosts and Guests, my second book of poetry, blends personal pieces about work and family with translations and more “objective” studies of city and animal life. Anonymity—part of what Césaire criticizes as the “sterile attitude of the spectator”—has always been a lure for me. In contrast to my first book, Anyone, Hosts and Guests works to establish more of a continuous identity and context for my speaker.

However, I remain drawn to the slippages of identification that come with imaginative experience. I wrote the poem below, “The Pokémon Go People,” after attending a party where some guests bemoaned the recent influx of Pokémon Go players upon their New England village. Though I had never seen the smartphone app, I took the side of the intruding gamers.

As I did a little research, I began to glimpse (or was it invent?) commonalities between the Pokémon Go player and the chameleon poet: a reliance on chance, a delight in role-playing, and a masochistic patience for the minor reward. Here, then, is a mask poem of a sort, which is to say that its concerns are entirely personal.

The Pokémon Go People

Not pretending to be shopping,

they canvass cobblestoned Water Street, near-sighted

as beach sweepers, their devices feeling ahead

for which alleyway, or corner of a yard,

might sprout a Snorlax, a purple Aerodactyl.

“These are the Pokémon Go people,” explains a villager

to her guest, careful not to point as one group passes,

their jean shorts to mid-shin, arms arabesqued

with dates or skewered hearts, some steering strollers.

Scattered among the 18th century colonials,

the Improvement Association’s clapboard plaques

remember Hale, ship captain, and Stewart, joiner,

each calling stenciled right beneath the name.

In this new life, vocation’s not so certain—

assignments can vibrate at any time, the location

of a needed creature flash, then disappear.

You almost have to be waiting there already,

disconsolate after a day of nothing

as light drains at the former hotspot in Cannon Square.

When two wild Pikachu clamber

over the rocks, the woman shrieks and punches her partner,

to make sure he’d seen. A postcoital quiet

on their drive back home to Pawcatuck.

(Originally published in The New York Review of Books)

Nate Klug is the author of the poetry collection Anyone and Rude Woods, a modern translation of Virgil’s Eclogues. His poetry has appeared in the Nation, the New York Review of Books, and The Best American Poetry. A Congregational minister, he lives in Albany, California.