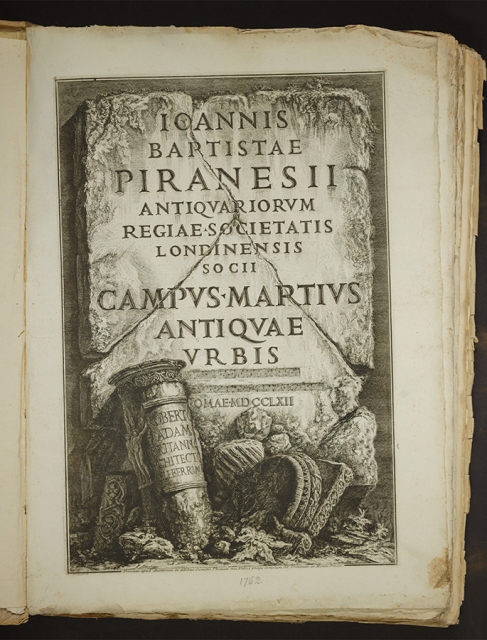

One of the central ideas that we explore in Piranesi Unbound is how a book comes together as the product of collaboration. As an artist, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1720–1778) worked in many forms and materials. He etched copper to make prints, designed architecture, and fused ancient and modern marble fragments to make chimneypieces and other decorative objects. Today he is probably best known as a printmaker who captured Rome’s dense layers, and yet when he made art, more often than not, he made books. We argue that Piranesi’s principal medium was the page, and examine how bookmaking brought other artists, printers, and patrons into his world. Our research into this dimension of his career was itself collaborative, a way of working that is not that common in our field.

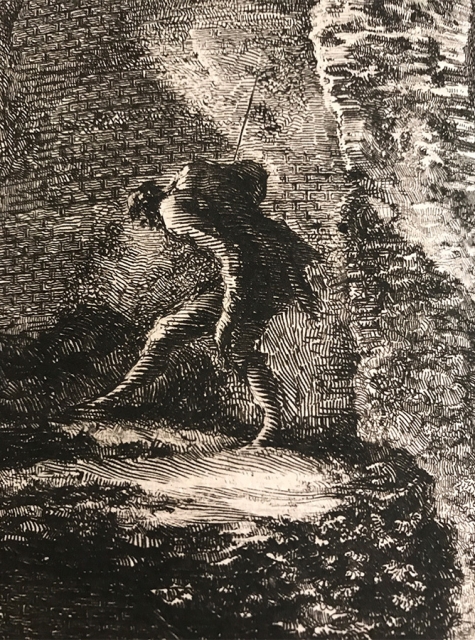

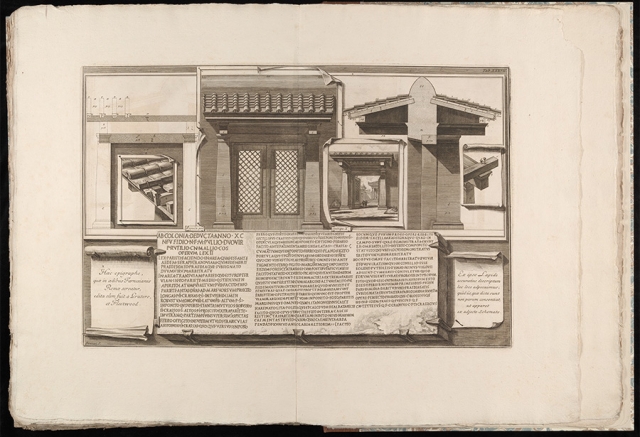

Piranesi’s chosen medium required complex work. He studied monuments and ruins with his artist friends, and later with his sons and apprentices. After making drawings, he etched copperplates, handing them over to his assistants to run through his presses. Scholars helped him compose texts, and other printers set his words in letterpress. Bundled together, his stacks of printed texts and images were then marketed and sold from the Piranesi house-museum, as his residence and workshop was known. Piranesi’s books were the results of a modern enterprise in which he tightly controlled the labor.

While we did not hunch over printing tables and rub sticky varnish on copperplates, we did work in ways that were sometimes similar to Piranesi’s methods. In our investigations, we relied on each other, and on specialists. Eighteenth-century book-making involved machines, but the results were still essentially hand-made objects. Each copy of a Piranesi book is unique, and owners could customize their copies in all kinds of ways. There are wonderful examples of destroyed copies, too—books that were cannibalized for their prints. The material qualities of Piranesi’s books and drawings were fundamentally important to our research, and we spent a lot of time tracking down crucial objects.

Our searches for drawings and rare books had us trawling auction results, sleuthing through library catalogues, and chasing down footnotes in pursuit of primary sources that seemed promising. But these were only the first steps of the hunt. Coming face-to-face with drawings and books was the next part of our research. From a Manhattan kitchen to the drawings cabinet at the Louvre, we traveled as a team to visit public and private collections. These trips allowed us to make some wonderful discoveries. One of our favorite topics became the parts of Piranesi’s drawings that usually don’t get published: the backs of the pieces of paper. What we found there was often as interesting as what he drew on the front.

Our intellectual workshop expanded. Sophia Bevacqua-Collins, one of our research assistants, spelunked in the storerooms of the Vatican Museums to track down an ancient relief that inspired one of Piranesi’s drawings and an inscription. We interviewed a type specialist to confirm a hunch about the printed characters that appear on many of Piranesi’s sketches. A trek to the Brooklyn Navy Yard to visit a printer allowed us to simulate this aspect of Piranesi’s world, as well as the title page of a book he never released for sale.

Because we live on opposite sides of the Atlantic, in New York and in Rome, we discussed everything that we found via Google Docs and What’s App. Eventually we shared our writing this way too, which meant exposing our jagged texts-in-progress to one another. This process was unusual for us, as it would be for many academics: most books in the humanities are written by a single author. Our collaboration began in the planning of an exhibition designed to celebrate Princeton University’s exceptional collection of Piranesi books, prints, and drawings. The research started locally, on the objects that will be in the show, which is now scheduled to open in September 2021. Things snowballed from there. Sharing discoveries with another person who finds as much pleasure in a subject as you do can be a powerful motivator.

Piranesi himself was an astonishingly productive person. He etched over a thousand copperplates in his career, produced reams of drawings, and designed all manner of objects. When you survey his output, his creativity seems endless. Looking at all of this from the angle of the books that he made, however, serves as an important reminder of how many other people were involved in those projects, and in what ways. Everything that we find in his books was in some way the result of one of his collaborations.

Heather Hyde Minor is Professor of Art History at the University of Notre Dame. She is the author of The Culture of Architecture in Enlightenment Rome and Piranesi’s Lost Words. Carolyn Yerkes is Associate Professor of Early Modern Architecture at Princeton University and the author of Drawing after Architecture: Renaissance Architectural Drawings and Their Reception.