In October 2020, I sat down with historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad for an event about my book, The Campus Color Line. It was a lively conversation, ranging from discussions about reparations in higher education to questioning who should lead U.S. colleges and universities.

In all, he offered a succinct synopsis of the book: “This is about the role of the university in the broader community.”

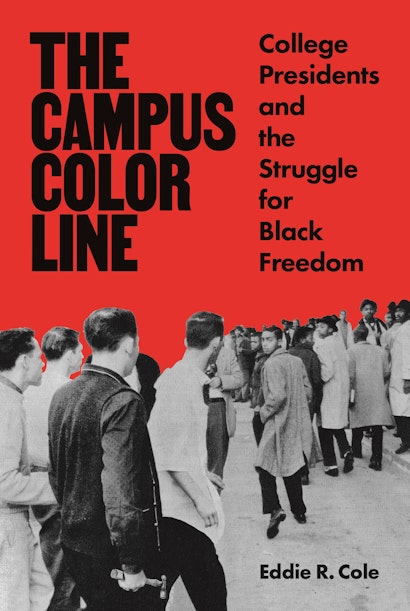

My book is a study of how college presidents and university chancellors shaped racial policies and practices during the mid-twentieth century. Yet, the historic structures of power explored in the book are the heart of the most pressing issues facing contemporary colleges and universities.

Power and race have remained eerily timely as readers have read and reflected on the book. In the past two years, presidents and chancellors have been forced to address a range of concerns about race and racism that have reemerged or been amplified since the book was published.

There is the demand to decrease budgets for campus policing alongside the critique over the disproportionate number of officer-initiated stops targeting Black people on or near campuses.

The Supreme Court has recently agreed to hear the latest affirmative action case—rekindling a decades-long debate over the use of race in admissions decisions at selective institutions.

Critical race theory—a conceptual framework that originated in critical legal studies—has stirred many lawmakers to ban nearly all elementary and high school teaching about race.

And in the last few weeks, Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) have been targeted with bomb threats—a continuation of the legacy of racism aimed at those institutions.

It does not matter if a president leads a public or private institution, a historically white or HBCU campus, or a college located in state controlled by a conservative or liberal majority—the American university is a site of power, and academic leaders must learn lessons from the past to better understand and leverage their power to address, and not replicate, racism on their campus.

The book has brought me into many conversations with current presidents and chancellors, provosts and deans, historians, educational researchers, activists, and readers who simply want to make sense of our world. There are unique lessons applicable to each group, but some are universal.

One universal fact is that previously mentioned racial issues—campus policing, affirmative action, attacks on teaching the truth about race, and racism toward HBCUs—are not new.

The expansion of campus police departments is linked to the physical expansion of college campuses in the 1950s and 1960s. As the footprint of campuses expanded, many neighboring communities—especially Black communities—were displaced. Crime was used as justification for the heavy surveillance and displacement placed upon those communities.

The original plans for affirmative action were also more comprehensive than the consideration of race in admissions to majority white campuses. In fact, the origins of those programs were largely targeted at aiding HBCUs, but over time, those initiatives were dismantled, leaving today’s debate an argument over the most narrowly conceived view of affirmative action.

The hijacking and repackaging of critical race theory echoes the McCarthyism-inspired attacks where civil rights efforts for racial equality were deemed communist activities and un-American.

Finally, the recent physical threats aimed at HBCU campuses remind me of the lives lost in the name of Black education over the years due to white supremacist violence aimed at students, faculty, and administrators who dared to challenge the racist ideas during Jim Crow segregation.

Too often, many fail to consider the historical context around the issues facing colleges and universities and, thus, try to address contemporary issues within the narrow vacuum of the present. This is evident in the media coverage about the contemporary issues mention above and, in turn, how presidents, chancellors, elected officials, activists, and others confront—or avoid confronting—racism on and beyond college campuses today. My book covers these issues.

The widespread praise for the book—its five book awards, the glowing book reviews, and tremendous reader engagement—are arguably the public metrics any author would desire. But of all the accolades, I constantly recall that comment about the role of the university in society.

The Campus Color Line offers the critical self-reflection on the past needed for us to ask: how are the structures of power embedded in universities dismantling or maintaining inequality?

Eddie R. Cole is associate professor of higher education and organizational change at the University of California, Los Angeles. Twitter @EddieRCole