Anyone who’s ever seen Sugar “Kane” Kowalczyk (Marilyn Monroe)—dressed in a form-fitting black skirt, frilly overcoat, and flapper hat, carrying a ukulele in one hand and a small, boxy suitcase in the other—making her grand entrance at the Chicago train station in Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot (1959) likely still has a relatively sharp memory of it intact. Wilder had his cameraman Charles Lang film the scene from the vantage point of Joe (Tony Curtis) and Jerry (Jack Lemmon), making an entrance of their own, clad for their first time in full drag to elude the mafia, with a little burlesque riff added to the score and a few tart comments underscoring their astonishment in observing Sugar offer a master class in walking in heels (“I tell you, it’s whole different sex,” insists Jerry). As Sugar saunters by, a burst of steam shoots out from the Florida Limited, tickling her hinter regions and giving a nod to another iconic scene from an earlier picture choreographed for Monroe by Wilder, billowy white dress perilously close to wardrobe malfunction as she’s perched above a New York City subway grate in The Seven Year Itch (1955).

But what most viewers likely don’t know is that the elaborate setup of an all-girl band boarding a train bound for Miami, scripted by Wilder and his long-time writing partner I.A.L. Diamond, likely has its origins in a much earlier piece of writing published by young “Billie” in his adopted hometown of Vienna when the author was still months shy of his twentieth birthday. Working as a cub reporter for couple of local Viennese tabloids, Die Stunde and Die Bühne, Wilder published a pair of pieces on the all-girl British dance troupe The Tiller Girls on European tour in April 1926. “This morning, thirty-four of the most enticing legs emerged from the Berlin express train when it arrived at the Westbahnhof station,” begins the first of these two articles, “The Tiller Girls Are Here!” which ran in Die Stunde on April 3, 1926. “The charming ladies to whom they belonged had stylish traveling outfits on, and one of the last to leave the sleeping car was a tall, elegant lady of a certain age, an old-fashioned hat atop her somewhat flattened head, a lorgnette in her right hand, whirling her left hand in the ir in the style of a musical conductor.” In the place of Sweet Sue, performed by Joan Shawlee in the Hollywood production some three decades later, there is a Miss Harley (“the shepherdess of these little sheep”) who serves as chaperone for the Manchester-based dancers.

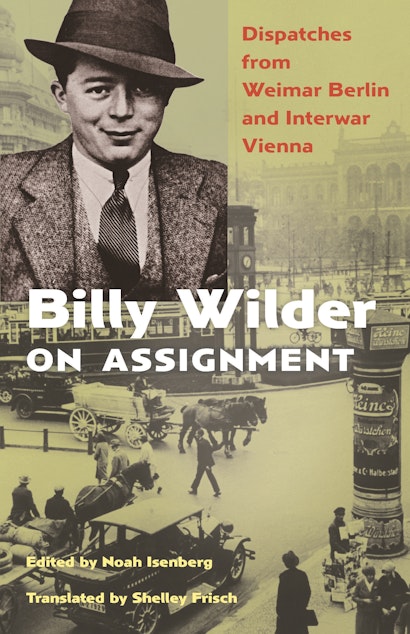

In the two pieces, which lie smack at the heart of Billy Wilder on Assignment, an anthology of fifty-odd previously untranslated Austrian and German articles by Wilder, the young journalist offers up much of the same puckish wit, the penchant for sexually charged mischief and pushing moral boundaries, and the chattiness of a born raconteur, all of which legions of future movie fans across the globe came to love. In the first instance, Wilder interviews the young British dancers, asking them a series of playful, vaguely amateurish questions (“Have you ever been to Vienna before?” “Do you dance the Charleston?” “What do you think of Einstein’s theory of relativity?” “Do you believe in love at first sight?”), while in the second he recounts the various excursions in an around Vienna guided by Miss Harley, with young Billie purportedly in tow. They visit the St. Stephen’s Tower, the bar at the old Sacher Hotel, and the Prater amusement park for a ride on its storied Ferris wheel. He laces both pieces with a string of sarcastic asides, an intermittent tease, direct address to his reader and quite a few unabashed attempts at post-adolescent flirtation. “Let’s stay indiscreet,” he writes in the piece’s final lines, “you even get a (harmless, unerotic, friendly, cousinly, for God’s sake obligation-free, forgotten the next minute…) little kiss, if you beg for one. God knows that’s no simple matter. But you get it.” To which he adds, with a wink and nudge, “Say it came from Billie.”

Admittedly, this is but one buoyant tale gleaned from a sweeping, more panoramic collection of short pieces, by turns irreverent, sweet, comical, and incisive, which together afford readers an early glimpse into the creative imagination of one of motion-picture history’s most talented and successful writer-directors. As the editor of the collection, I am of course just a smidge biased, but certainly no more than the young, swagger-prone Billie himself.

Noah Isenberg is the George Christian Centennial Professor and Chair of the Department of Radio-Television-Film at the University of Texas at Austin. The author, most recently, of We’ll Always Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood’s Most Beloved Movie (W.W. Norton, 2017), he is currently completing a book on Some Like It Hot. You can follow him on Twitter @NoahIsenberg