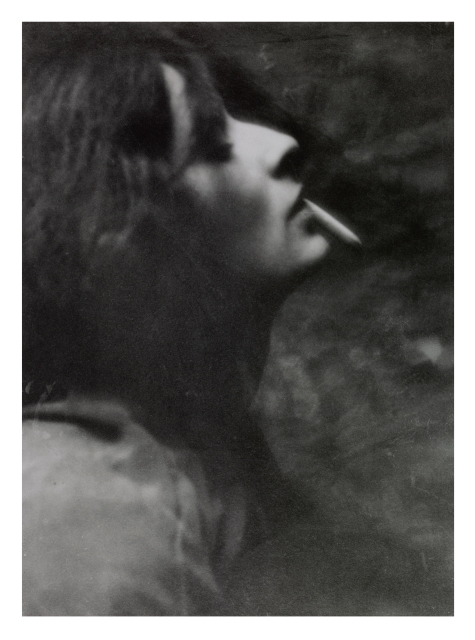

Not since Marcel Duchamp curated Mina Loy’s last one-person exhibition in New York at the Bodley Gallery in 1959 has the latter artist risen above the obscuring cloud of mystery and notoriety that set to her heels in 1914 when her writing was first published in the magazines Camera Work and Trend. While literary historians have well embraced the breadth and force of her writing canon,[1] art historians have yet to firmly dip their pens to ink for the modern marvel that was Mina Loy. Her creativity defied categorization, and her superlative and complex persona deflected focus. The artist Mina Loy was at once a shooting star, a lunar beacon, and a constellation unto herself.

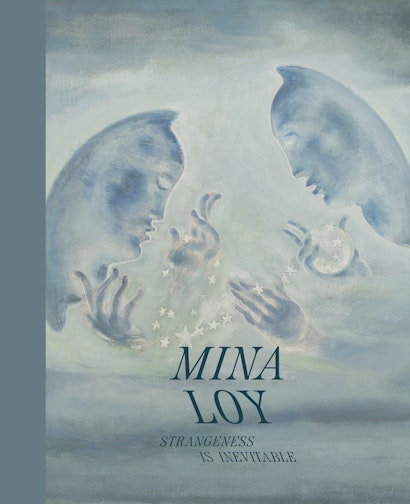

The publication Mina Loy: Strangeness is Inevitable, which accompanies the retrospective exhibition currently on view at Bowdoin College, aspires to introduce the doozy that was Dusie,[2] as she was called by her first husband, Stephen Haweis, and the enclave of artists, writers, and cultural impresarios that enlivened Florence, Italy in the early 1900s. Their ranks included Mabel Dodge, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Giovanni Papini, Gertrude Stein, and Carl van Vechten, all who found Loy brilliant and evanescent and so encouraged her to launch her mind and creative spirit into the world.

Most likely, the moniker Dusie was an amalgam of the proper German pronouns (Loy had studied in Munich as a teenager) for “you,” du and sie, one the familiar and the other formal—a play on Loy’s distracted air, wit, and startling intellect, packaged awkwardly in Victorian mannerisms. Her singular poetic métier was welcomed up and down the social ladder throughout her life, in every country she deigned to adorn with her beauty or revile with her consideration.

This unrelenting play in her demeanor—between esprit and genius—landed her out in front of the literary avantgarde in America upon the delivery of her Futurist-inflected poems to New York by Mabel Dodge and Carl Van Vechten. Ezra Pound soon credited her as the source of logopoeia, “poetry… akin to nothing but language which is a dance of the intelligence among words and ideas,”[3] and the New York avantgarde quickly affirmed her as the harbinger of Futurism, Dada, and unprecedented linguistic scandal. This Loy of the word is known.

Yet the veritable Loy, manifest elsewhere. The one poised to rise to consideration out of the obfuscating mire of history, who worked through the social upheaval that followed both World Wars and the cultural erasure set in place by the economic devastation of the Great Depression. This Mina Loy was a maker of things, a visual artist, who throughout her life was a dedicated and innovative painter, portraitist, inventor, industrial and fashion designer. This omnivorous nature of her creativity is perhaps the primary reason that her artistic ascendency has yet to be integrated into the annals of art history.[4] As William Carlos Williams wrote in his introduction to the 1958 publication of Loy’s Lunar Baedeker & Time-Tables, which first bent the ear of twentieth-century literary scholars toward Loy, “Mina Loy was endowed from birth with a first-rate intelligence and a sensibility which has plagued her all her life facing a shoddy world.…But it has hurt her chances of being known.”[5] Are we surprised that a woman of keen intellect and an unclassifiable aesthetic could find no place for herself in this world? If she had been born fifty years later, there is little doubt her polymathic aspirations and inimitable creative capacities would have found more enabling reception. To quote Loy’s own Feminist Manifesto of 1914, “Leave off looking to men to find out what you are not. Seek within yourselves to find out what you are. As conditions are at present constituted you have the choice between Parasitism, Prostitution, or Negation.” Loy elected negation.

The effervescent web of Loy’s multivalent creative expression hung on what many identified as her excessive “cerebral” nature. Surely a man has never been called out as too cerebral. The term was applied by critics to her poetry as well as to her much-desired dinner conversation. She was in fact too smart for her own good, as she stated, “I have indulged in all the useless inanities but never the profitable delirium of the ambitious.” Such a lack of accommodation to social convention and expectation for her as a woman often made putting food on the table difficult. “If at least I had been expert in inconsequence I might have married a statesman—but there again—cabinets do not conserve the gestures of Pan because it is impossible to be both cognizant and important—it is probable that I must renounce success.”[6]

And cognizant she was.

The machinations of Loy’s intellect were precise and unrelenting in their pursuit of truth and an understanding of the human condition. Her fortitude and authenticity as an artist were why Duchamp, and the remainder of her best of the best cohort from her years in Paris—Djuna Barnes, Robert Coates, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim—all showed up for Loy’s Bodley Gallery even though she was not in attendance. It was their salute to a fellow art warrior. Loy had remained true to her call as an artist and fought nobly against the world and its conventions, the heavens, and her circumstance.[7] And like them, except for their brief halcyon days in Paris, she had nowhere found a home. She had earned their respect and deep affection.

Jennifer R. Gross is a modern and contemporary art curator and scholar whose books include The Société Anonyme: Modernism for America.

Notes

[1] There still remains numerous unpublished and unstudied manuscripts.

[2] Mina would remain throughout her life a conundrum to those in her intimate circle, ever present, ever removed. As an art student, she was literal a doosie, meaning “splendid” or “stylish.”[2] Du-sie implicitly includes the affable familiarity and the distant reserve implicit in Mina’s nature, carriage. Her charm would lure in and yet repeatedly her friends would comment on her emotional reserve or fatigue even before she experienced the traumas that were to come in her life.

[3] WAP p. 160

[4] This coupled with her notoriety as a poet, global itinerancy, elliptic public presence due to her lifelong battle with incapacitating depression, and her spiritual sourcing of her artistic ambitions have overshadowed her artmaking and complicated scholars approach to her widely dispersed, ephemeral art.

[5] LLB p. xvi

[6] Parmar page 46, from box 2 archived manuscript page Goy Israels: Fragments YCAL MSS 6, Box 2, folder 30.

[7] Januzzi 418 “anyone with my brain & no education & no memory would be in a lunatic asylum from the struggle for adequate expression. But little Mina goes Battling on—” Esau Penfold?