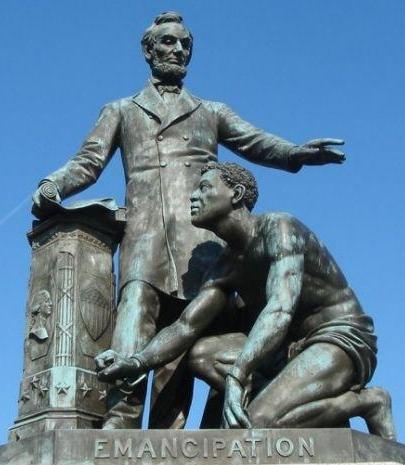

The Emancipation Memorial sits imprisoned in a cage in Washington’s Lincoln Park, waiting to hear whether it will be exiled or set free. Unlike Confederate statues, which have essentially lost the public debate over removal, this monument to a national hero and a noble cause has sparked a growing division of opinion, both at the site and in the press.

The monument was born in 1876 as the Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, so named because free blacks—mostly soldiers in the Union army—had paid for it. One particular freedman was plucked out of obscurity to become the model for the crouching man below Lincoln, the first representation of “the Negro” in a national monument.

He was a strikingly handsome middle-aged farmer from Missouri, named Archer Alexander. Born into slavery, nonliterate, his own ancestors stolen from him, he was the kind of person history usually forgets. He was included in the monument only because he happened to cross paths with a highly influential, sympathetic white man who gave him shelter at a time of need. In so doing Alexander became, at least in part, the creation of Rev. William Greenleaf Eliot, a founder of Washington University in St. Louis and the grandfather of poet T.S. Eliot.

Eliot was a Yankee minister who had moved to Missouri decades before the war and had to learn how to live with the brutal institution of slavery all around him. It was Eliot who chose the design for the monument, after visiting artist studios in Italy. It was Eliot who arranged for photographs of Alexander to be made and sent to the sculptor in Florence so that he could remold the crouching man’s face in Alexander’s likeness. And it was Eliot, a decade after the monument went up, who wrote and published The Story of Archer Alexander from Slavery to Freedom, a little volume that has defined Alexander’s life story ever since.

Riddled with mistakes and misrepresentations, Eliot’s book is more about himself than about Archer Alexander, who had been dead almost five years when the author composed it. With no one to contradict him, Eliot painted Alexander as “happy, contented, and grateful,” and “in many things only a grown-up child.”

A startling description for a man who had escaped his enslaver in the midst of the Civil War and traveled forty perilous miles to seek protection from the top Union army officer in St Louis. Missouri was one of four Union border states where slavery remained in force. The Emancipation Proclamation exempted the entire state, and Confederate sentiment ran high in the county where Alexander escaped. For respectable white citizens like Eliot, Alexander’s experience was quite literally incomprehensible.

Alexander not only escaped successfully, but he convinced the U.S. Provost Marshal in St. Louis to give him protection papers. With these in his pocket, he found work with Eliot at his St. Louis home tending to his garden and orchard. A few weeks later, a gang of men sent by his enslaver traced his escape route and found him in Eliot’s fields. They beat him unconscious with clubs and guns, then detained him at the city jail with the full cooperation of the local authorities. When the Provost Marshal learned of the outrage from Eliot, his men rescued Alexander at gunpoint and jailed the attackers.

While Eliot’s book infantilized this brave and determined man, it also paradoxically inflated him into a Union war hero. In one brief paragraph Eliot reported that Alexander had escaped because he had learned that some local Confederate sympathizers had sabotaged a bridge over which Union troops were set to pass. After he walked five miles to tip off a Union man, the bridge was repaired and the troops saved, but Alexander had to flee for his life when his role in the affair was exposed.

For reasons that have yet to be explained, this was not the story Alexander himself told the Provost Marshal in April 1863, with Eliot present. Alexander said nothing then about a bridge but talked instead about a stash of guns hidden by local rebels in an icehouse, to which he and a black comrade had alerted the local Home Guards.

Whichever version (or both) was true, Alexander’s action was remarkably courageous: he had informed on traitors and had to escape to save his life. He was hoping that the Provost Marshal would grant him freedom, not just protection, but it turned out that risking his life for the Union cause wasn’t good enough. The Army officer kept Alexander’s status in limbo, so Eliot arranged safe harbor for him in Illinois until Missouri passed its own emancipation act and it was safe for him to return.

A final twist of fate: in 2018 Muhammad Ali’s family discovered through genetic testing that the legendary boxer and activist is Alexander’s direct descendant.

Archer Alexander’s path to freedom was complicated and arduous, requiring great personal courage mixed with perseverance, timely assistance, and epochal events. His is the sort of messy history that monuments usually ignore. When Eliot wrote that using Alexander for the likeness of the negro converted the Emancipation Monument into “the literal truth of history,” he was spouting utter nonsense.

There was nothing “literal” about Alexander’s nudity or his pose. In reality the sculpture is a collage of fact and fantasy – a real person’s head shot inserted into a generic figure that was itself a reworked version of the old abolitionist emblem depicting a kneeling black man pleading, “Am I not a man and a brother?” For those people who see the figure rising, do what I ask my students to do: take the pose, if you can. It’s contorted but static, precariously balanced by a couple of knuckles on the left hand. It’s quite possible that no one in the history of the world has ever been in this pose, except the artist himself, who modeled it with mirrors, or the art history students I’ve asked to replicate it.

The peculiar pairing of the two men is squarely in the image tradition of saints miraculously curing the lame or the blind. But it doesn’t take an art history PhD to get this, or to realize that the two men aren’t working together in “mutual agency,” as some have recently argued.

Frederick Douglass, who gave the oration at the 1876 dedication of the monument, certainly did not see it this way. At the occasion he did not utter a single word of praise for its design, a remarkable departure from tradition for dedicatory speeches. And shortly afterward, as two historians have recently discovered, he published a letter critiquing the design as out of step with the current struggle for citizenship and equal rights, saying that before he died he wanted to see “a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.”

Both Eliot and the monument he chose willfully distorted history. Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, held by the bronze hero in his right hand, never freed Alexander. He had to free himself through his own will and determination, as did so many thousands of other enslaved people across the South.

Perhaps this is why Alexander “laughed all over” when Eliot finally showed him a picture of the monument. But according to the minister, Alexander eventually “sobered down,” got himself into the right frame of mind, and said gratefully, “Now I’se a white man! Now I’se free!”

In Eliot’s act of ventriloquism, the black dialect cancels the very meaning of the statement. To say “I’se a white man” proves that Alexander isn’t white and can never be, just as his bronze figure can never rise to Lincoln’s level and become white. Eliot was a compassionate man and a loyal friend, but his book was just like the monument: condescending to its black “hero” and defensive of white men like himself who had accommodated to the institution of slavery despite their moral opposition to it.

Archer Alexander should be honored. But Eliot’s monument, like his book, infantilizes the man and conscripts him into a story of virtuous white paternalism, not black self-determination. Alexander deserves better than this monument. We all deserve better.

Kirk Savage is the William S. Dietrich II Professor of History of Art and Architecture at the University of Pittsburgh. He is the author of Monument Wars: Washington D.C., the National Mall, and the Transformation of the Memorial Landscape (Princeton) and the editor of The Civil War in Art and Memory.