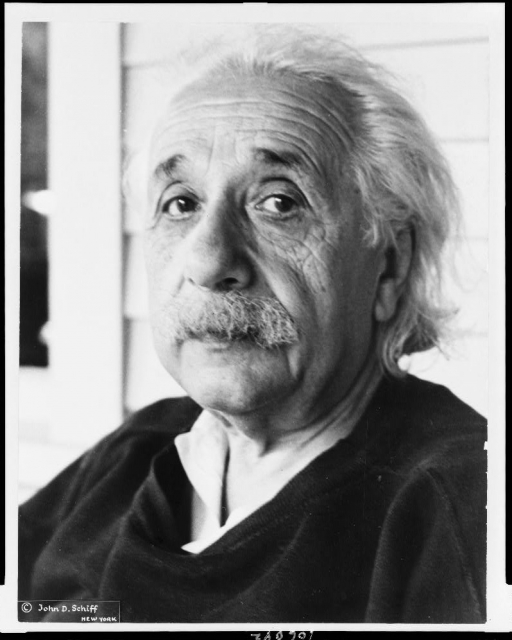

Albert Einstein’s time on earth ended on April 18, 1955, at the Princeton Hospital. In April of 1955, shortly after Einstein’s death, a pathologist removed his brain without the permission of his family, and stored it in formaldehyde until around 2007, shortly before dying himself. In that time, the brain of the man who has been credited with the some of the most beautiful and imaginative ideas in all of science was photographed, fragmented—small sections parceled to various researchers. His eyes were given to his ophthalmologist. These indignities in the name of science netted several so-called findings—that the inferior parietal lobe, the part said to be responsible for mathematical reasoning was wider, that the unique makeup of the Sulvian fissure could have allowed more neurons to make connections. And yet, there remains the sense that no differences can truly account for the cognitive abilities that made his genius so striking.

Along with an exhaustive amount of information on the personal, scientific, and public spheres of Einstein’s life, An Einstein Encyclopedia includes this well-known if macabre “brain in a jar” story. But there is a quieter one that is far more revealing of the man himself: The story in which Helen Dukas, Einstein’s longtime secretary and companion, recounts his last days. Dukas, the encyclopedia notes, was “well known for being intelligent, modest, shy, and passionately loyal to Einstein.” Her account avoids any trace of the sensational.

One might expect a story of encroaching death, however restrained, to chronicle confusion and fear. Medically supported death was a regular occurrence by the middle of the 20th century, and Einstein died in his local hospital. But what is immediately striking from the account is the simplicity and calmness with which Einstein met his own passing, which he regarded as a natural event. The telling of this chapter is matter of fact, from his collapse at home, to his diagnosis with a hemorrhage, to his reluctant trip to the hospital and refusal of a famous heart surgeon. Dukas writes that he endured the pain from an internal hemorrhage (“the worst pain one can have”) with a smile, occasionally taking morphine. On his final day, during a respite from pain, he read the paper and talked about politics and scientific matters. “You’re really hysterical—I have to pass on sometime, and it doesn’t really matter when.” he tells Dukas, when she rises in the night to check on him.

As Mary Talbot writes in Aeon, “Apprehending the truth that all things arise and pass away might be the ultimate groundwork for dying.” And certainly, it would be difficult to dispute Einstein’s wholehearted dedication to the truth throughout his life and work. His manifesto, referenced here by Hanoch Gutfreund on the occasion of the opening of the Hebrew University, asserts, “Science and investigation recognize as their aim the truth only.” From passionate debates on the nature of reality with Bohr, to his historic clash on the nature of time with Bergson, Einstein’s quest for the truth was a constant in his life. It would seem that it was equally so at the time of his death. What, then, did he believe at the end? We can’t know, but An Einstein Encyclopedia opens with his own words

Strange is our situation here upon earth. Each of us comes for a short visit, not knowing why, yet sometimes seeming to divine a purpose….To ponder interminably over the reason for one’s own existence or the meaning of life in general seems to me, from an objective point of view, to be sheer folly. And yet everyone holds certain ideals by which he guides his aspiration and his judgment. The ideals which have always shone before me and filled me with the joy of living are goodness, beauty, and truth. To make a goal of comfort or happiness has never appealed to me; a system of ethics built on this basis would be sufficient only for a herd of cattle.

Read a sample chapter of An Einstein Encyclopedia, by Alice Calaprice, Daniel Kennefick, & Robert Schulmann here.

Debra Liese is Curator of Ideas and Content Partnerships at Princeton University Press.