The sting. Pain is what we associate with the word “wasp,” because our definition of wasp is far too narrow. We equate them with belligerent social hornets, yellowjackets, and paper wasps. We are conditioned by family, friends, pest control companies, and the media to fear and despise them. In reality, the overwhelming majority of wasps are solitary, small or minuscule, and either cannot sting, or are loathe to do so in self-defense. Wasps are perhaps the most diverse of all organisms, especially if you include the other members of the order Hymenoptera, the bees (hairy wasps) and ants (wingless wasps).

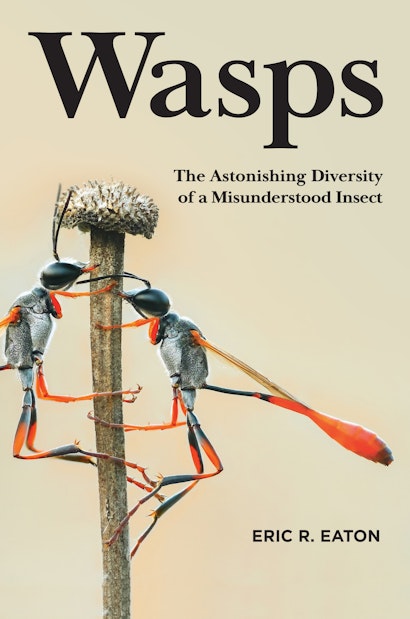

There is no question that wasps can be intimidating. They are so successful at advertising their venomous nature that many other insects mimic them. That “wasp” you are avoiding could easily be a harmless black and yellow fly, moth, beetle, or true bug disguised as a wasp. Meanwhile, the spear- or whip-like filament protruding from the rear of a wasp is not a sting at all, but the female’s egg-laying organ, called an ovipositor. She is very particular as to where she deploys it, and she never sticks it into a human. A true sting is usually retracted inside the abdomen of the insect until it is firmly implanted and causing pain.

Wasps have a mind-boggling array of lifestyles. Most are active during the day, but some are nocturnal and may fly to your porchlight at night. Some wasps have vegetarian larvae. Others are food-stealing kleptoparasites of other wasps. By far the most common life history is that of a parasitoid. That is, a parasite of other insects that eventually kills its host. It is the larval stage that is the parasitoid, but the adult female is the one which must locate the host. Fairyflies, less than a millimeter, carry out their younger life stages entirely within the egg of another insect. At the other extreme are enormous mammoth wasps, cicada killers, and tarantula hawks. The larvae of sawflies, the most primitive of wasps, resemble caterpillars and feed on plants. Gall wasps turn various parts of plants into incubators for their larvae.

Mud daubers, potter wasps, mason wasps, and social wasps are master architects, fashioning raw materials into elaborate nests to protect their vulnerable egg, larva, and pupa offspring. A colony of yellowjackets can number in the hundreds, and the adult female worker wasps vigorously defend the helpless brood housed in the paper combs inside their nest. Solitary wasps, by contrast, are quick flee at your approach because the number of their offspring are few, and the nest usually well concealed.

Adult wasps need carbohydrates to fuel their energetic activities of nest-building and host-seeking, so they are often seen drinking nectar from flowers. They also consume fermenting sap from wounded trees, and the sugary waste of aphids and related insects. Called “honeydew,” this substance is especially important during periods when flowers are scarce. In urban areas, our barbecues and picnics are another source of sweets: the beverages we drink. Some species of yellowjackets are scavengers, so they also steal chunks of meat to take back to their nest. Wasp larvae need protein to grow, and a morsel of chicken or fish will do nicely.

To live in peace with wasps, take simple precautions. Consult your physician to determine whether your immune system is hypersensitive to wasp stings, and follow your doctor’s advice if you are allergic. Do not serve canned beverages outdoors, lest a wasp crawl in unseen and sting when you take a sip. Avoid reaching into crevices and cavities that you cannot see into. There may be a wasp nest tucked inside. Periodically inspect your property for nests of social wasps, especially before using equipment that would cause vibrations that disturb the wasps. Mark nests with flags or stakes so family and friends know to avoid the nest. Nests are abandoned at the first hard frost, and not re-used the following year. Remove mud wasp nests only when you can see obvious, round emergence holes that indicate the nest is no longer occupied. Even then, other solitary wasps, or bees, may refurbish old nests, the insect equivalent of flipping. Screen attic vents to prevent wasps from entering in the first place.

While we may experience personal conflicts with wasps, human enterprise would fail were it not for their activities. They are pollinators, and non-toxic agents of pest control in agricultural systems and your own garden. They inspired improvements in the manufacture of paper. Their venom shows promise in creating new medicines, and they are important research subjects in fields as diverse as biomimicry, ethology, and chemical ecology. All wasp species have value, of course, though it may not be obvious, or directly relevant to your everyday life. Their unsung ecosystem services make the world go round.

Eric R. Eaton is a writer, editor, and consultant who has worked as an entomologist for several leading institutions, including the Smithsonian and the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden. He is the lead author of the Kaufman Field Guide to Insects of North America and the coauthor of Insects Did It First. He runs the blogs Bug Eric and Sense of Misplaced. Twitter @BugEric