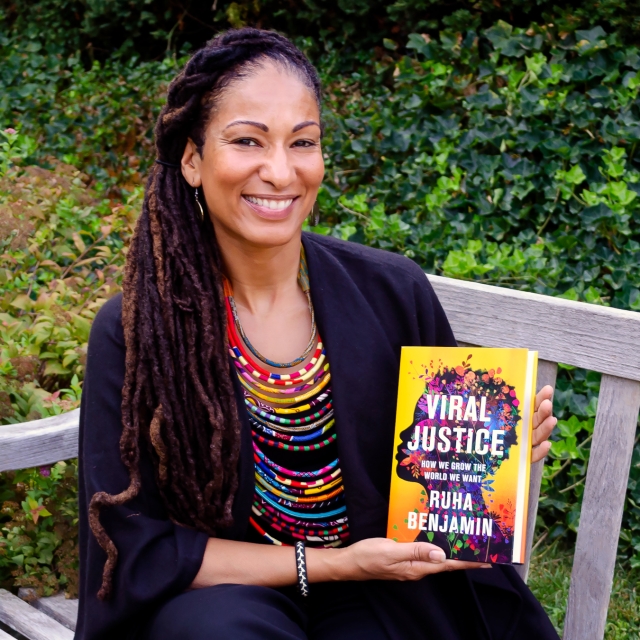

In spring 2020, Ruha Benjamin received a DM on Twitter from her literary agent Sarah Levitt: “I’m hungry to read anything you have.” Inspired, Benjamin began writing and spent the first few months of the pandemic conceiving what would become her new book, Viral Justice.

In the book’s introduction, Benjamin takes COVID-19—which we’re used to encountering in negative terms—and turns it upside down, exploring its potential for engendering hope and social change. She writes: “What if … we reimagined virality as something we might learn from? What if the virus is not something simply to be feared and eliminated, but a microscopic model of what it could look like to spread justice and joy in small but perceptible ways?”

Benjamin, a professor of African American studies, studies the social dimensions of science, medicine and technology. She joined Princeton in 2014, received the President’s Award for Distinguished Teaching in 2017 and was named an inaugural Freedom Scholar in 2020. She is the author of “Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code” and “People’s Science: Bodies and Rights on the Stem Cell Frontier.” She created the Ida B. Wells JUST Data Lab at Princeton, which brings together students, educators, activists and artists to rethink and retool data for justice.

Benjamin often uses the idea of speculative world-building in the classroom, encouraging students to ask, “What if?” In Viral Justice, she adopts a world-building rubric everyone can participate in. Elevating dozens of stories of real people whose individual actions and seemingly small decisions have effected widespread change for a more just world—what Benjamin calls “everyday insurrections and beautiful experiments”—she invites readers to cultivate their own plots of hope.

“[E]very single one of us can weave new patterns of thinking and doing … drawing on our varied skills, interests and dispositions,” Benjamin writes. “We need the loud and ferocious world-builders as much as the quiet and studious ones. The last thing we need is for everyone to do or be the same thing!”

On Oct. 11, she kicks off a 20-city book tour across the U.S., Europe and Africa, including an appearance at 7 p.m. Oct. 27 at Princeton Public Library in an event co-sponsored by Labyrinth Books and Princeton’s Department of African American Studies and Humanities Council.

Here, Benjamin unpacks how writing Viral Justice offered her hope during the pandemic, why she ditched her bird’s-eye view as a trained sociologist in order to focus on the individual, and what it felt like to put personal details from her own life into a book for the first time.

You began work on this book during the first months of the pandemic lockdown in spring 2020. You write: “I quickly realized that writing was exactly the daily therapy I needed, churning all those apocalyptic headlines and social media notifications into something that might, in the end, offer some nourishment.” Could nourishment lead to hope? Would you share how the book illuminates what hope looks like to you right now?

RB: In Viral Justice, I consider hope as something we do, not just something we feel, and writing for me is a hopeful act. If “hope is a discipline,” as Mariame Kaba reminds us, that means we can practice hope. We can strengthen it, like a muscle, that powers our work. We can seed hope, and water it so that it grows, nourishing our efforts to make this world more joyful and just.

To be clear, practicing hope doesn’t mean ignoring or downplaying the gloom and doom that surrounds us. Quite the opposite. It means reckoning honestly with the state of the world but not stopping there. It means refusing to surrender to fatalism or wallow in cynicism. In academia, especially, we can become self-righteous in our critical understanding. But then what?

This was the question nagging me when I first started this book, and the original title was “Viral Racism.” But then I remembered what one of my mentors told me: “As scholars we spend so much time naming the world we don’t want, we can forget to imagine the world we do want.” This led me to Viral Justice. And although I dive deep into the many problems making us sick, the book shines a light on people far and wide who are practicing hope by resisting and reimagining business as usual.

In the book’s introduction, you talk about your hesitance, as a sociologist, to focus on the role of individuals in social change. What was that ambivalence about, and why did it feel important to embrace the individual?

RB: We already live in a hyper-individualistic society, so I worried about focusing too much on the role of individuals in social change and how that might reinforce our default cultural setting. Plus, my training as a sociologist focused so intently on the role of social forces and institutional processes in shaping people’s lives, so I get an allergic reaction when I hear talk of “individual responsibility” and “individual intention,” especially in conversations about inequality and oppression. But this led me to downplay individual volition in maintaining and transforming the status quo. Social systems, after all, rely on each of us playing along or questioning the rules of the game.

Viral Justice shines a light on everyday people who refuse to cede power, seeding it instead.

As you focus on individuals, you unpack how seemingly minor decisions and habits can spread “viral justice.” Can you tell us about one individual from the book—not someone famous but a “regular person”—who captures your vision for the way that small changes can help build a more just and joyful world?

RB: There are sooo many! So hard to choose. There’s educator Calvin Terrell leading transformative justice workshops in the aftermath of school violence, “Nap Minister” Tricia Hersey leading a movement to resist grind culture and revalue rest as a form of reparation, Ron Finley, the “Gangsta Gardener” turning sidewalks into edible gardens and food deserts into food sanctuaries, and Sarahn Henderson (who delivered my older son) working with Black birth workers in Georgia towards an expansive vision of reproductive justice in a state where community-based midwifery is still not legal.

In addition to many individuals I profile, there are numerous groups and organizations we can learn from. Philly Jobs with Justice (JwJ), for example, has been fighting for fair treatment of working people since 1999, including a new campaign to ensure wealthy nonprofits like universities are good neighbors, and contribute their fair share to local public schools. What I love is how JwJ focuses on concrete changes—like wage raises and sick days for campus workers and increasing how much universities contribute to public schools—while also seeding an expansive vision of solidarity that brings together students, labor unions, faith groups and communities. It’s that combo of short-term wins and long-term world-building that exemplifies viral justice.

The book is a mix of memoir and social analysis. In Chapter 5, “Exposed,” you talk about your experience as a senior at Spelman College, at age 23, married and pregnant, giving the valedictory address a week after giving birth. Tell us about the Toni Morrison quote that inspired you at that time, and about how you hope revealing your own lived experiences and vulnerabilities will inspire readers.

RB: I figured that if I am asking people to reflect deeply on how their personal lives connect to their public commitments, then I had better do the same. I can’t expect readers to be introspective if I wear the mask of a “cool, calm and collected scientist” to borrow a phrase from famed sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois. One of many experiences I share in the book is the one you mention, about how it felt to be a young, pregnant and Black college senior at Spelman.

The year before, while researching for a junior term paper, I came across a 1989 Time interview with Toni Morrison [the Robert F. Goheen Professor in the Humanities, Emeritus, who died in 2019] in which she was questioned whether “the crisis” of teenage pregnancy shut down opportunity for young women. “You don’t feel these girls will never know whether they could have been teachers?,” the interviewer asked her. Morrison replied:

“They can be teachers. They can be brain surgeons. We have to help them become brain surgeons. That’s my job. I want to take them all in my arms and say, Your baby is beautiful and so are you and, honey, you can do it. And when you do, call me—I will take care of your baby.”

Although I wasn’t a teenager, I still felt the cultural stigma perpetuated by policymakers and popular media that comes with “being a statistic.” But I soon found myself buoyed by family, friends and midwives who had torn up that cultural script and seemed to take Toni Morrison’s gospel to heart, “Your baby is beautiful and so are you and, honey, you can do it.” This is exactly the kind of stubborn love and support that I hope Viral Justice encourages more of in readers.

The book’s subtitle “How We Grow the World We Want” kicks off your use of gardening analogies—the sower and the uprooter, identifying your plot—to help readers imagine viral justice. And you’ve expanded the book into a monthly newsletter “Seeding the Future: A place for bloomscrolling to balance out all our doomscrolling.” What is your best advice to help readers find their own “plot” to cultivate blooms and not doom?

RB: I’d say, think about what you love and what brings you joy, but also, what pisses you off? Of all the injustices in the world, what makes your blood boil most? What keeps you up at night? ‘Plotting’ is about conspiring with others, it’s about rewriting cultural scripts, and working in our own backyards. But, most of all, it’s about getting our hands dirty in the messy work of world-building.

This interview was originally published by Princeton University Office of Communications.

Jamie Saxon is an arts and humanities writer at Princeton Office of Communications.

Ruha Benjamin is an internationally recognized writer, speaker, and professor of African American Studies at Princeton University, where she is the founding director of the Ida B. Wells Just Data Lab. She is the award-winning author of Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code and editor of Captivating Technology, among many other publications. Her work has been featured widely in the media, including the New York Times, the Washington Post, CNN, The Root, and The Guardian.