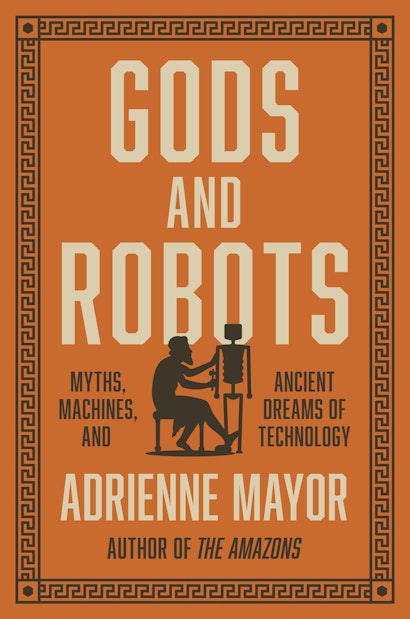

Adrienne Mayor is the author of Gods and Robots, the fascinating untold story of how the ancients imagined robots and other forms of artificial life—and even invented real automated machines. In honor of Women’s History Month, we asked her to share some of the women writers who inspired her work on this book—and those who have captivated her since childhood.

Thinking about women whose writings have inspired me since childhood is a happy assignment. There are far too many to list, but here are seven. As a young bookworm in South Dakota, I haunted the public library and eagerly anticipated the Bookmobile’s weekly visit.

I was reading the “Little House on the Prairie” books while my new elementary school, named after Laura Ingalls Wilder herself, was being built in the cornfield across the street from my house.

Captivated by the adventures of self-sufficient, independent kids free to roam without any grownups around, I loved the Moffat and Pye families created by Eleanor Estes (1906-1988). Based on her own childhood in the early 1900s and told with dry humor, Estes’ plots were filled with serious, real-life details. The kids gathered coal lumps on train tracks to keep warm in winter, investigated mysterious events, and recovered a kidnapped puppy—I was not a big fan of magic or fantasy.

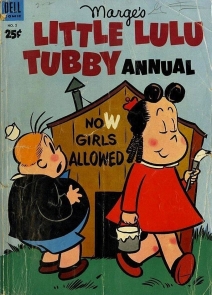

Estes, a children’s librarian, wrote award-winning Children’s Literature. But I was spending my allowance on another sort of literature. Namely, comic books by the pioneering female cartoonist Marjorie Henderson Buell, the creator of Little Lulu. That smart, daring, sassy, audacious little girl who made her own rules was my first feminist hero.

My other favorites were The Phoenix and the Carpet and Five Children and It by E. Nesbit (1858-1924). A British socialist, Nesbit took up writing children’s books to support herself. Like Estes, E(dith) Nesbit had lost her father at an early age and was raised by a mother who struggled to make ends meet. Her stories were set in Edwardian England and the children were usually home alone, free to roam the countryside and London, not mention fabulous excursions to ancient Egypt and Babylon. Now, E. Nesbit’s plots did involve magic but in such a pragmatic fashion that the magic often became a nuisance and bother, compelling the five young siblings to be resourceful and inventive to survive the fantastic situations they found themselves in. As Gore Vidal noted in his review of Nesbit’s works (NY Review of Books), her boys and girls are intelligent, sarcastic, cruel, compassionate, selfish, cooperative, arrogant, funny, impulsive, rude, thoughtful—like adults but also like real children. Eleanor Estes, Marjorie Buell, and E. Nesbit were all unsentimental distillers of “the essence of childhood,” and their books are good to read at any age.

I Married Adventure, the autobiography of Osa Johnson, was another beloved book of my youth. Osa left Kansas to become an adventurer and documentary film pioneer who explored faraway Africa, the South Pacific, and Borneo in 1917-37. She and her husband each flew their own amphibious biplanes; they lived in tents and encountered exotic wild animals–with their primitive Eastman-Kodak movie cameras whirring all the while. I read Osa’s memoirs countless times, day-dreaming over the sepia photos, imagining where I might travel one day.

One scientist who inspired my own research and writing was Dorothy Vitaliano. A geologist, she invented the discipline of “geomythology.” In her path-breaking book Legends of the Earth: Their Geologic Origins (1973), Vitaliano proposed that scientific details of catastrophic natural disasters such as earthquakes, volcanoes, and floods were preserved in folklore, myths, and legends around the world.

While working on Gods and Robots: Myths, Machines, and Ancient Dreams of Technology, I developed renewed admiration for Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) written when she was nineteen. I hadn’t realized how strongly Shelley’s story was shaped by her knowledge of philosophy, science, and classical mythology about Prometheus, who fabricated the first humans and gave them fire. Shelley portrayed Victor Frankenstein the “modern Prometheus” for her era. I’m in awe of her ability to weave Immanuel Kant and alchemy, occult transference of souls, and advances in chemistry, electricity, and human physiology so marvelously into a timeless and gripping science fiction tale—at such a young age.