Parking: NG 7975131393 – Trailhead: NG 8089432135

Getting there: From the A87, either over the hills from Balmacara Square (1 km uphill take the right fork to Plockton) or take the Plockton road from Kyle of Lochalsh. Both routes arrive at Duirinish. Over the bridge at the top of the village and take the next right (Achnandarach ¾ à). After less than 1 km, park on the edge of the wide entrance of the forest track on the right (leaving room for forestry vehicles in the highly unlikely event access will be needed while you are there). Stroll eastward, uphill. Don’t hurry. You’re not going far and there’s plenty to keep you pteridologically busy.

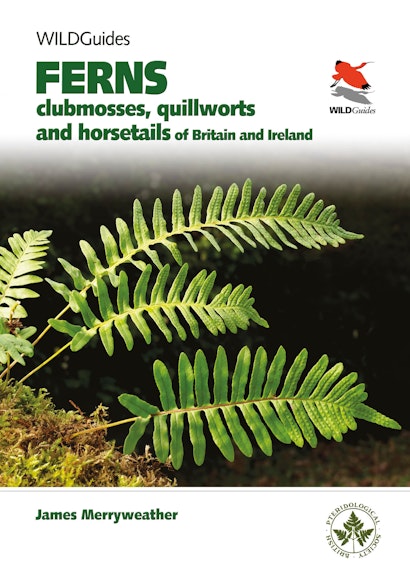

Even better than a shady bank scattered with the fresh June fronds of Beech Fern Phegopteris connectilis (p. 214) interwoven with bluebells, stitchwort, red campion and spikes of Wood Horsetail Equisetum sylvaticum (p. 122) is a roadside verge with thousands of Beech Fern fronds, stretching as far ahead as you can see and spilling down the bank into the woodland alongside. I came across this marvellous sight recently, shortly after the WildGuide Britain’s Ferns became available in June 2020. It was beside the narrow back road along Gleann Casail, near Plockton in the West Highlands. To say that the entire verge was carpeted would be to exaggerate, but there were numerous extensive patches of densely packed fronds along a full 100 metres of roadside, from near the beginning of the walk as far as one could see.

Looking east, the bank on your left falls steeply away to the damp woodland floor, by a small meandering burn (stream), shaded by several massive oaks plus hazel, rowan, downy birch, ash and, closer to the burn, sallow. On the right side of the road there is a well vegetated roadside ditch from which a well-drained bank rises, overtopped by birch, sallow and hazel. There are as many different ferns as you might decently expect to find along a few hundred metre stretch of roadside on a sunny June afternoon.

As usual, Male Ferns are present. First, Common Male Ferns Dryopteris filix-mas, soon joined by Golden D. affinis, Borrer’s D. borreri and farther on occasional Narrow D. cambrenesis. (pp. 226-241; as usual, careful consideration needed). Only Mountain Male Fern was absent, yet it is abundant on a similar roadside bank less than 4 km away. The much more easily identified Lady Fern Athyrium filix-femina (p. 206) and the inevitable Lemon-scented and Hard Ferns Oreopteris limbosperma (p. 212) and Struthiopteris spicant (p. 204) were plentiful.

Of the tripinnate Buckler Ferns, Hay-scented D. aemula, was expected but surprisingly absent, but we are fortunate to have the Broad and Northern Bucklers, D. dilatata (p. 246) and D. expansa (p. 248) side-by-side. The book warns readers not to be too confident of identifying D. expansa, and I am often uncertain when I think (hope?) I have found it. But it is very likely to be found in this part of the country and at this place it offers the great convenience of having its alternative right next-door for comparison. Even with this luxury, you will find yourself uncertain and it is best to range around, comparing as many specimens as possible.

For the time being, forget the stripiness or otherwise of the rachis scales. They are too often sufficiently striped (or ‘shadowed’) to assume D. dilatata, even when other features have—you thought—confirmed D. expansa. You can check later and if they are not striped, that can be your verification. If they are, then other characters will decide, or if not, you must assess other plants. That should be enough to succeed, but if still uncertain, just WOB (p. 93).

Bucklers are present—if you did not realise immediately on arrival, you will soon find out—you can legitimately use colour difference as a guide, but only as a guide. Please be careful. Colour is variable, subjective and dependent upon awkward factors, such as an individual’s colour vision. We really should provide Pantone references or easily obtained Dulux paint colour charts are just as good, so that natural colours may be compared standard examples and then communicated effectively to others. A person can describe a fern as, for instance, Minted Glory 1 or Emerald Delight 3, or even determine a range of shades for each, to see if—with reference to proper diagnostic characters—they distinguish species. But remember, use colour only as a guide. So, D. dilatata tends to be darker and bluish green than the mid-green of D. expansa.

With the two Buckler Ferns side-by-side (p.47), the degree of flatness or downward curving of the pinnules can be easy to differentiate (both characters illustrated above), particularly if you can refer to a range of specimens, as you need to if you are going to reach confident identifications. Then, consider the length if lowest pair of basiscopic pinnae compared with the adjacent pair. Shorter or equal with ‘recurved’ pinnules: D. dilatata. Longer with more-or-less flat pinnules: D. expansa. Now check the scales and reassess colour shades, and base your identification on the balance of all characters, as in the table on page 47.

All very satisfying, and now you have the Achnandarroch bus stop in sight. Soon there are several huge D. cambrensis in the shade to your left and a patch of dark spruce plantation on the right. Just out of the plantation, opposite the bus shelter, there is a patch of three large different Male Ferns growing together, a good test for revising your identification abilities. So far, you have strolled only about ½ km, though it has taken a long time. Turn here or continue. There is less than 1 km farther to go.

Continuing past the bus stop junction there is almost impenetrable wet woodland on the right, but the verges might turn up something of interest, such as the single Hard Shield Fern Polystichum aculeatum on the near edge of the ditch. This fern is usually found where there is a constant base-rich trickle of water. Who knows what has encouraged it to grow on a dry road verge?

Soon, you will approach Loch Lundie, an old reservoir that used to supply Plockton. A few years ago—for reasons best known to themselves—the authorities dropped its level, exposing an ugly band of marginal lake bed, which is at last beginning to become vegetated. Immediately on arrival by the loch there are the scattered spikes of Field Horsetail Equisetum arvense and ahead, in the loch, there is a colony of Water Horsetail E. fluviatile. To ensure that the first is not the hybrid of these two E. x litorale, make good use of the quick test demonstrated on page 54. Is E. palustre here, perhaps on the original shore margins? Turn here or continue.

Just one pteridophyte remains to be found, towards and at the eastern end of the loch: Common Quillwort Isoëtes lacustris. You might be able to see it from the bank but be prepared to wade into the shallows to find it. Both straight and curly forms grow here, often together (pp. 110–111. Figs 1, 5 & 9 were photographed here).

Whether you stopped at the bus stop, the beginning of the loch or its head, simply retrace your route back to the car, a pleasant stroll that allows you once more to enjoy the unusual ‘acres’ of Beech Fern along the verge. Of course, there is one more fern that hardly needs a mention: Bracken Pteridium aquilinum.

James Merryweather has been studying ferns for more than fifty years, developing a particular interest in their identification and ecology. Having learned so much from generous pteridologists past and present, he now eagerly shares that knowledge and experience with others. He is an enthusiastic member of the British Pteridological Society, which promotes the study of this fascinating group of plants.