As the reality of the pandemic set in, faculty, students, and administrators scrambled to adjust to the sudden switch to online teaching. I learned to navigate Zoom with a toddler at home and my students packed up their dorms and prepared to finish their coursework elsewhere. The lucky ones headed home to reunite with loved ones sooner than expected. Others had to contend with unstable homes or housing insecurity. For many first-generation and low-income students, returning home muddled an already complicated set of ethical and emotional challenges. The upcoming semester will not be any easier. As colleges and universities contend with the costs and benefits of different instructional modes, it is critical that we understand the potential impact of those decisions on this population of students.

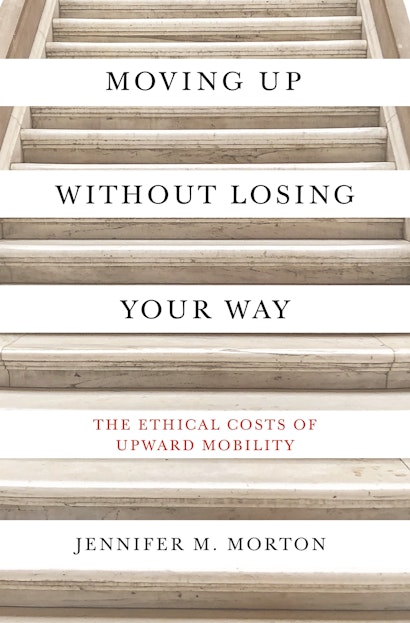

College has the potential to be transformative for students—financially, personally, and ethically. Many arrive at college seeking a degree that will lead to a career and better job prospects, but they are also aspiring to become more independent, to discover their passions, and to make their families proud. For first-generation and low-income students who seek mobility through education, accessing its potential benefits is not as simple as working hard. Strivers, as I call these students, are often torn between pursuing their own educational and career ambitions and remaining closely connected to their families, friends, and communities. With a foot in both worlds, they must make difficult ethical trade-offs about what and who to prioritize. Sometimes prioritizing their own educational development can come at the expense of relationships with their communities, families, and friends. In my book Moving Up Without Losing Your Way, I call these the ethical costs of upward mobility because they are costs to aspects of a striver’s life that are meaningful and valuable.

Colleges can help mitigate these ethical costs by offering students the opportunity to develop new relationships, find new communities, and explore the sort of meaningful interests and projects that will form the backbone of a striver’s evolving identity. At a residential college, like the University of North Carolina—Chapel Hill where I teach, the distance from home offered by campus life makes it easier for strivers to develop into their new selves while retaining some control over how connected they stay to the communities from where they hail. The pandemic has scrambled that model. This past term, I taught a first-year seminar composed mostly of strivers. During the first part of the semester, I saw them contend with the challenges that strivers often face—determining their place on campus while retaining a sense of identity and connection with their homes. As the pandemic hit, I heard from students who struggled with playing support roles for family: many became babysitters and homeschool teachers to siblings or cousins, others started working full-time at grocery stores, and some dealt with tense family situations that grew ever more fraught as the weeks went by. I heard from students who missed their new college selves, but, as a parent, I was heartened by how many were enjoying being back home with their families.

As universities and colleges consider whether to have courses in person or online, the calculus for strivers will be complicated. Online education has the potential to enable all of us to maintain social distancing and greatly minimize our risks of catching and spreading Covid. Though young people are less likely to experience the most serious effects of the virus, they can transmit it to others who are more vulnerable. Dining hall workers, janitors, professors, and others who work with students are put at risk when we congregate thousands of young people in indoor spaces. And yet, without in-person instruction and campus life many strivers will find it hard to develop the sorts of connections and relationships that enable them to enter the new world that higher education promises. We know that the more students feel connected and involved socially and emotionally to college, the more likely they are to graduate.1 Face-to-face interactions allow strivers to learn how to interact in a social world that might play by different rules than the ones they are used to and that is populated by people who grew up very differently than they did. Although, as we are all learning, virtual connection is a valuable tool in allowing us to maintain and nourish existing relationships, it’s less clear that it is as potent a tool in enabling the development of new relationships in the way that a chance encounter at the cafeteria or at a student club can. Furthermore, many students who learn from home will be living in situations in which learning will be difficult—parents who have lost their jobs or who are essential workers, siblings who are home from school, and lack of internet or a quiet place of their own in which to study. I fear how many more strivers will not complete their degree given the challenges that this pandemic has laid upon their young shoulders and how many will never show up on the first day.

But this does not mean that the right decision is to hold classes in person. One of the arguments I make in my book is that there are decisions in which we face ethical costs no matter what we do. When a striver decides to leave their community to pursue their own education, they might experience regret and guilt at what they are leaving behind. This does not mean that their decision is wrong, but rather that the situation is ethically fraught and the right response in such cases is to feel conflicted. The situation confronting higher education right now is similar. There are important goods on both sides. If we go online, we will save many people from death or serious illness. But we might also lose some students that we might not have lost otherwise and make it very difficult for others to complete their degree. If we go back to campus, some strivers will develop the sorts of connections that will keep them engaged in higher education. But the potential catastrophic human cost to our communities is a likely, terrifying outcome. We ought to feel conflicted whichever way we go.

Jennifer M. Morton is associate professor in the Philosophy department at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She is the author of Moving Up Without Losing Your Way.

Notes

[1] Tinto, Vincent. Taking student retention seriously. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University, 2007.