My passion for paperbacks began back in the year 2000 with my first job in book publishing. Prior to that, as a philosophy graduate student, I was enamored of finding hardback editions, ideally jacketed, of the philosophers whose works I was reading. I wasn’t after first or rare editions; in fact, as a grad student I couldn’t buy those even if I wanted to, so the cheaper the better as means were, shall we say, limited. My friends and I would trawl used bookstores in search of such unmined hardcover gems. This was still the days before instant gratification was a few clicks away on used book sites like Advanced Book Exchange or Alibris. But as I embarked upon my new life in book publishing, I also began my life as a commuter; first by bus, from Northern New Jersey to Manhattan, later by subway from Brooklyn. I suddenly and surprisingly found my book-buying habits altered as a result of my mode of transport.

This was a time before I had a smartphone to occupy my every non-occupied moment. Nor did I yet own a laptop—let alone one small and light enough to tote with me daily—to maximize my productivity. Work, particularly email, was largely and blissfully still office bound. In fact, I didn’t always need to carry a shoulder bag or backpack and often had just a book on me as I headed out in the morning. Imagine that, just a book! Now I have backpack that includes a notepad (for some reason), a crumpled printout of something months old (and still unread); a laptop and enough cords, chargers, adapters, and a spare battery pack to ensure my screens will always remain aglow. And of course, a book which more often than not remains dim within the confines of said bag. But hope springs eternal that reading time will manifest itself (presumably when a solar flare darkens all of our devices). The main way to occupy myself on my commute, besides sleeping, was reading a book. It was then that I realized the ideal book for my travels was the mass market paperback: the 4 ¼ × 7-inch book that could easily slip into my inside coat or back pocket, ready to be retrieved and read at any possible moment of downtime. I was on the verge of a conversion experience.

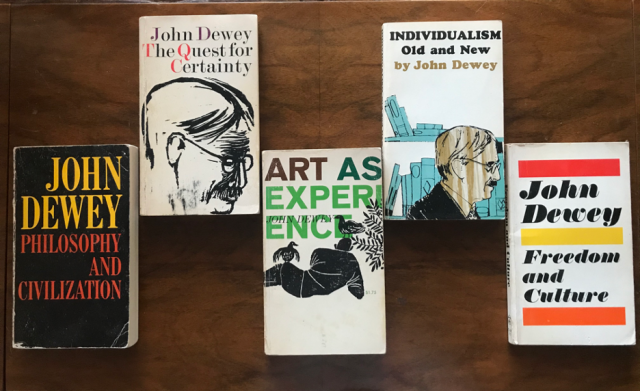

On the day that I was offered and accepted my job as editorial assistant at Oxford University Press (I believe it was a nanosecond between their offer and my acceptance), I went for coffee with a friend to our local Barnes and Noble, at the time one of the few such stores with a used books section. I made, as usual, a beeline straight to the used philosophy section. But before I could make it there, I was stopped dead in my tracks as I passed a cart of books waiting to be priced and shelved. I stood agog as arrayed before me were a collection of books by the philosopher John Dewey, all in my now much desired mass market paperback size.

As a philosophy student I had been very interested in American Pragmatism, particularly the work of Dewey, so this moment itself seemed like a divine dispensation from the paperback gods. I ecstatically gathered an armful, took them to the clerk, and breathlessly asked, “how much?” Seeing him mark each inside cover lightly with a penciled “$2,” made me almost giddy. He remarked, “Wow. You seemed excited about these.” Little did he know of my plot to continue my abandoned graduate studies aboard the 163 NJ Transit bus line to Port Authority.

A move to Brooklyn a few months later resulted in a new commute, a subway journey on the Q train over the Manhattan Bridge into midtown. My need for these pocket-sized books did not abate, and I kept a stack near my apartment door for easy access as I headed out for work or any other excursion that might afford some time to read. That was the beauty of the mass market paperback. It was noncommittal. It was there as needed in my pocket ready at hand. With it I would never be without reading material—something my phone would later ensure was always the case at the expense of the book I still, with the best of intentions, insisted on carrying with me.

My own realization of the beauty and usefulness of a book that fit in one’s pocket was not unlike the story behind the origin of that Ur-mass market paperback, the Penguin Classic. The world has a train delay to thank for one of the wonderful and woefully underrated inventions of the last century. Publishing lore has it that Allen Lane, the great British publisher, was waiting on a train platform lamenting his lack of something to read. He looked around and observed other impatient passengers in a similar predicament. He saw in this dearth a market opportunity and returned to his office with the idea that his publishing house could produce cheap, pocket-sized editions of classic works that could be sold in places other than bookstores such as—you guessed it—train platforms. Thus, was born the ubiquitous fixture of twentieth century literature—the Penguin Classic paperback.

As I rummaged through used bookstores, stoop sales, and street bookseller tables in NYC, I began to amass quite a large collection of these mass market paperbacks. What dawned on me as I accumulated my stockpile was that although they shared a trim size with Harlequin-style romance and pot-boiler detective novels, many of the mass market paperbacks I had penchant for were not exactly light reading. In fact, I was particularly drawn to pocket-sized editions of some of the classic nonfiction works of mid-century. I began to realize just what a great hope and admirable faith this evinced on the part of paperback publishers at the time.

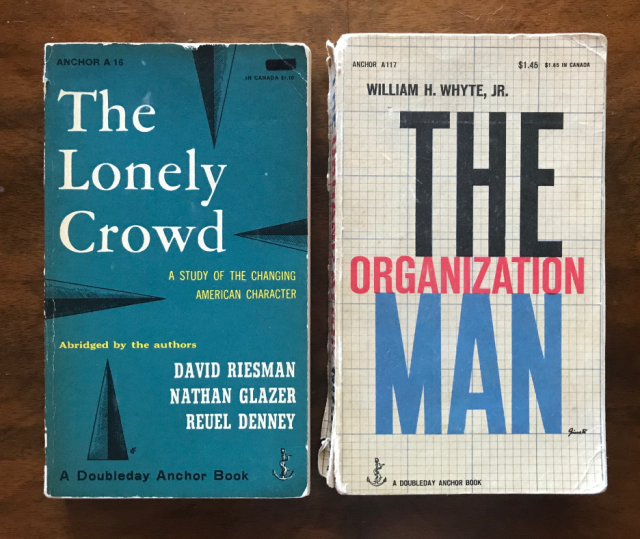

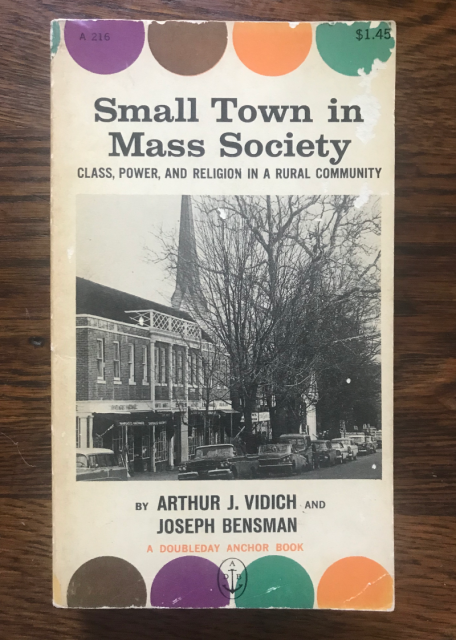

It was during the heyday of these editions, the 1950s and 1960s, that famed American publisher Jason Epstein, inspired by Penguin and Pelican in the UK, created—in 1953, when he was only 25!—the iconic Anchor Doubleday paperback series.1 This time was what intellectuals of the period referred to, often with a downward glance, as the era of “mass society” (a term that appeared in the title or copy of many a mass market paperback). Not only was the postwar educated American middle class growing exponentially, but there was an explosion of returning GIs and then their boomer offspring attending college and being assigned these books.2

I am in awe of the ambition of these paperback imprints. It was a publisher’s field of dreams: “if we print it cheaply and price it right, they will come.” Theirs was a fervent faith in an appetite among the aspirational middle classes and their progeny to read or at least aspire to read such heady social science works and canonical classics. And judging by how many paperbacks one can still find marked up and dog-eared at book sales and used bookstores, it’s clear that those publishers were on to something. Can there be a better ambition for a paperback book? Although pocket-sized mass market paperbacks have been largely replaced, with notable exceptions, by the more durable but larger trade paperback (a format I also love), the aspiration to reach readers by making books available in that particular format remains to my mind one of the great and lofty goals of mid-century, middlebrow (to me a term of endearment, not disparagement) publishing. It is a faith which continues to inspire my own publishing tendencies.

The pocket-sized paperback lives on in publishing ventures like Oxford University Press’s laudable Very Short Introductions—of which unsurprisingly I have also curated a collection. The books in this series are organized as primers on an ever-increasing wide range of topics by leading scholars. I always fancied myself as supplementing the lacunae in my education as I read these primers on the subway (Next stop: The Renaissance!). I even had the honor as a young assistant editor at Oxford of signing up a VSI, the shorthand by which they are know to many, on Alexis de Tocqueville. Call me crazy, but who doesn’t want to learn about the great de Tocqueville’s life, work, and ideas in 120 pocket-sized pages!?3 Again, the belief now, as it was then, is that a book in the right size and format, for the right price, will inspire people to read and learn and be ready at hand, literally.

I developed a habit or, perhaps an affectation, of never leaving home without one of these mass market paperbacks in my pocket or bag (I even have a couple in the car, just in case). With no explicit intent of showing off (I swear!), I once pulled from my sport coat pocket an Anchor Doubleday paperback while having a drink with a professor of philosophy. He picked it up from the bar, held it like Proust’s memory-laden Madeleine, smiled, and said “I haven’t even seen one of these for years.” Having grown up in the New York area in the 1960s, he remarked, “my generation was reared on paperbacks like Anchors. We used to call them our ‘poor man’s Harvard education.’” Knowing that phrase was also used to describe the fabled City College in New York City, I reached out to that philosopher to confirm my recollection for this piece. He didn’t recall the exact phrase he used to describe them, but said it does sound like something he would have said and it certainly reflected how he thought of those books. He then proceeded to recall in charming detail the mass market paperbacks he was in fact reared on including the one that inspired him to become a philosopher when he actually made it to Harvard, David Hume’s Essays on Human Understanding. He purchased it as a high school student from the rotating wire rack in the bookstore in Penn Station while waiting to board a Long Island Railroad train. He concluded by saying “It was a great time for paperbacks.” Indeed it was.

So, when you next have an unoccupied moment and feel that now familiar, practically second nature, urge to reach for your phone, perhaps pick up a paperback instead. Pocket-sized preferably.

In the meantime, enjoy this brief photo gallery of some classic mid-century paperbacks.

Happy Paperback Day!4

-

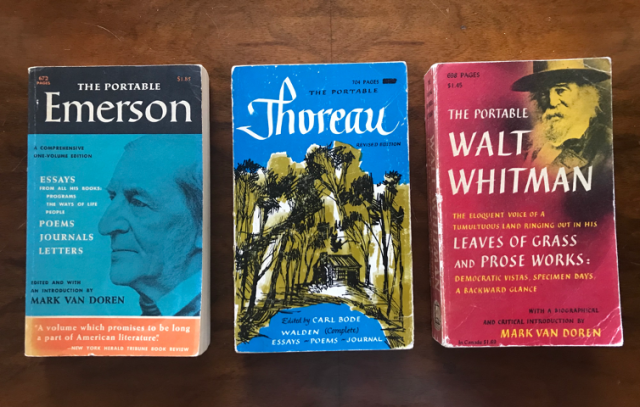

Emerson, Thoreau, and Whitman. All perfectly portable and, thus, perfect fits for Viking’s wonderful and popular Portable series.

-

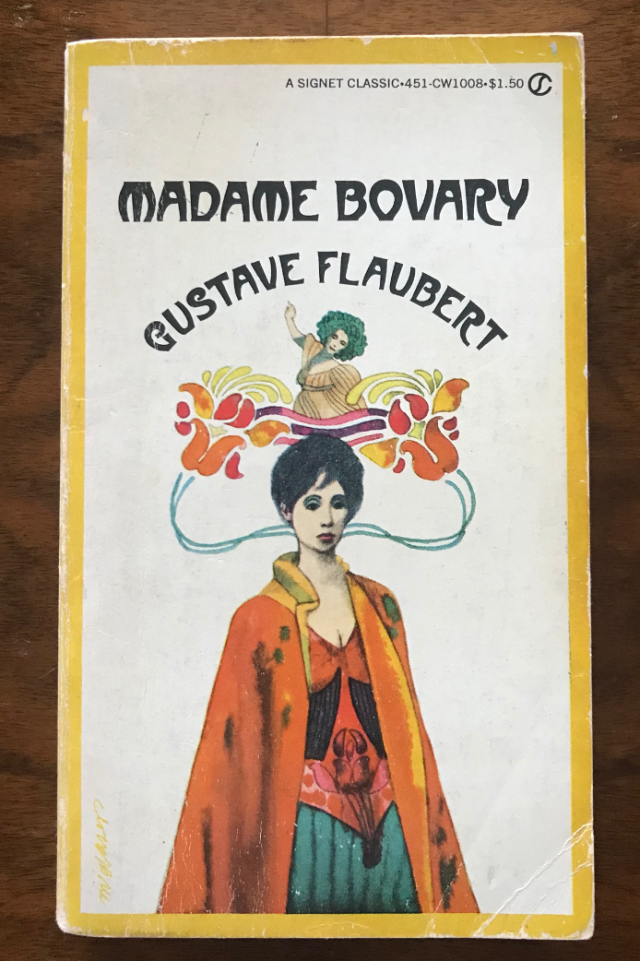

Signet Classic published this take on Madame Bovary for the Age of Aquarius.

-

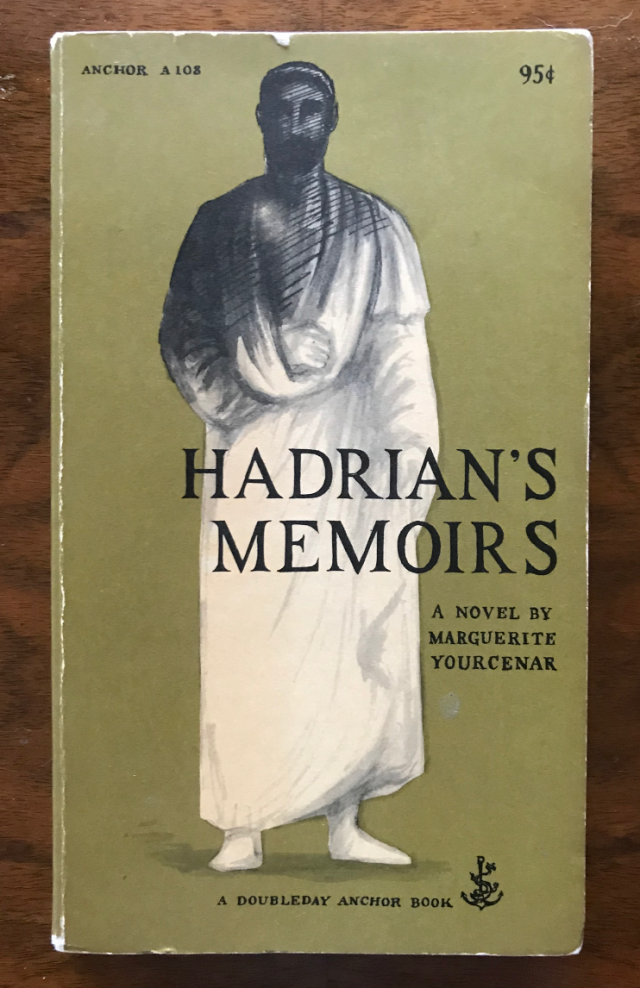

Fans of the great illustrator Edward Gorey may recognize his distinctively dark style on this classic work of historical fiction. That’s because Gorey started his career as a book illustrator for Anchor Doubleday! Find out more about Gorey’s delightful book cover art here.

-

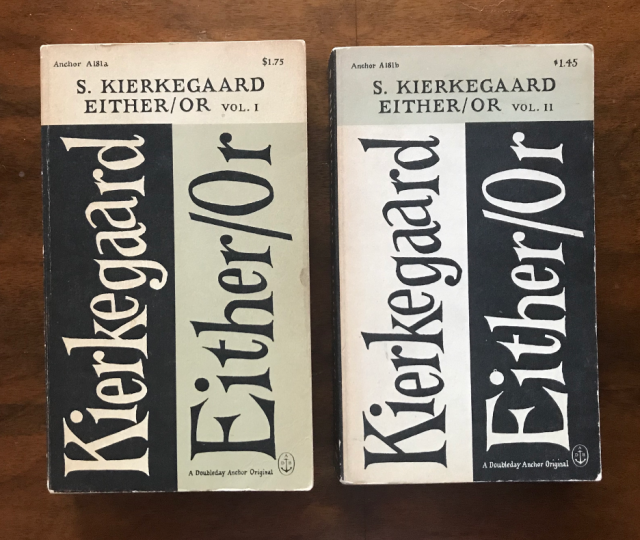

Kierkegaard and Gorey. A perfect match! I do wonder why vol. II is $.30 less than vol. I though.

-

More Kierkegaard and Gorey. A true Kierkegaardian classic that made its debut at the peak of existentialism’s influence in America. This edition is a repackaging of Princeton University Press’s translation of these two works by Walter Lowrie, who is almost solely responsible for introducing the great Dane’s writings to American audiences. PUP reissued Lowrie’s translation in our own mass market-sized edition in 2013.

-

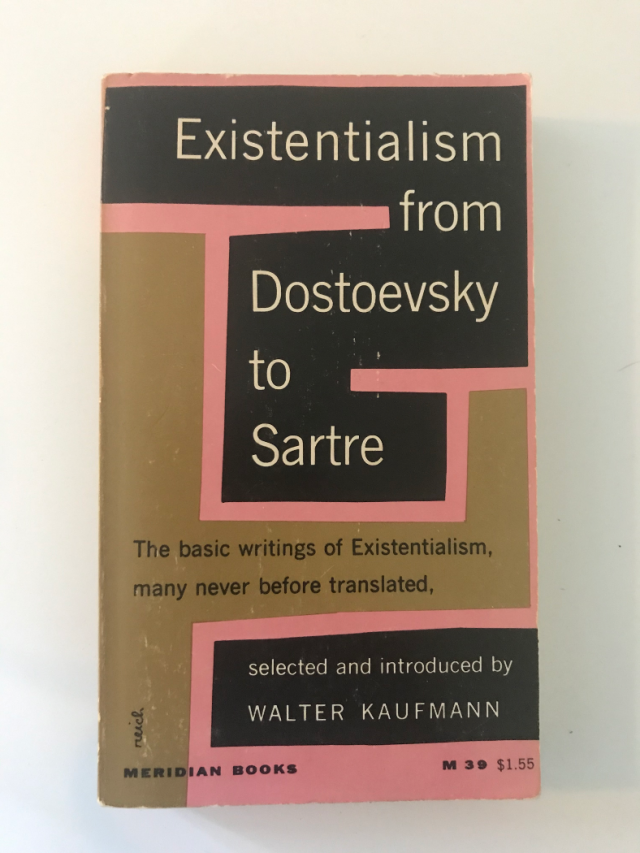

Speaking of existentialism, this classic anthology by Princeton philosophy professor Walter Kaufmann was a near-ubiquitous feature adorning college dorm room shelves in the 1950’s and 1960’s. The influence this book had on a generation is not to be underestimated.

-

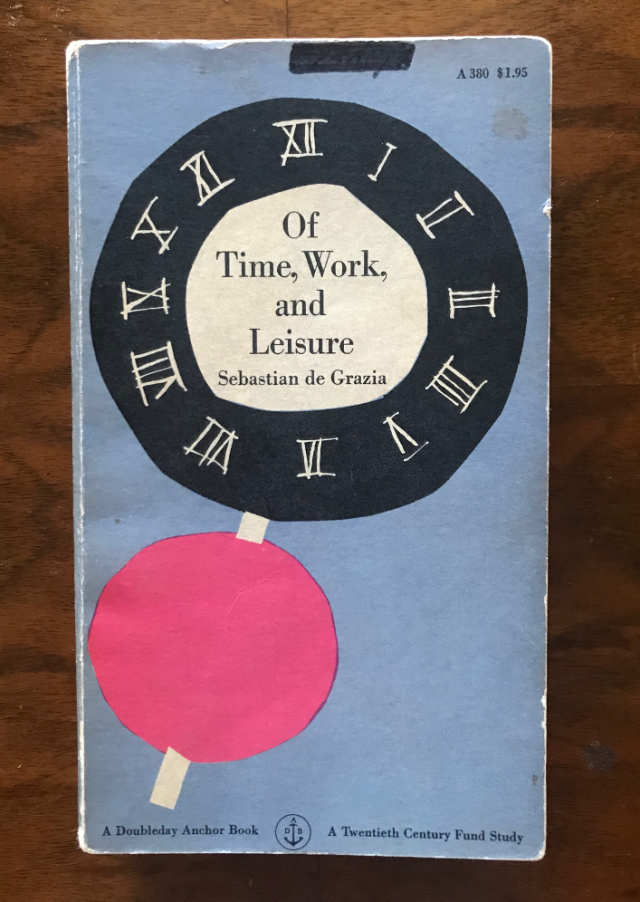

Another social science classic by the Pulitzer-Prize winning author of Machiavelli in Hell, Sebastian de Grazia. Cover by one of the master of mid-twentieth century design, Paul Rand.

-

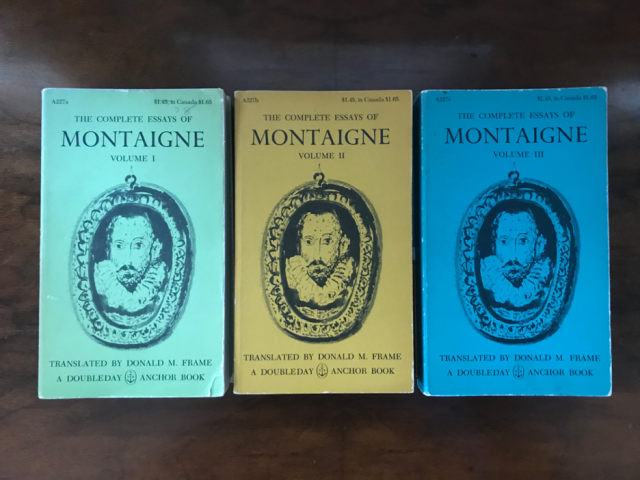

The many selves and paperback covers of Montaigne. His complete essays as translated for Stanford University Press by Donald Frame but repackaged in three handy volumes by Anchor Doubleday.

-

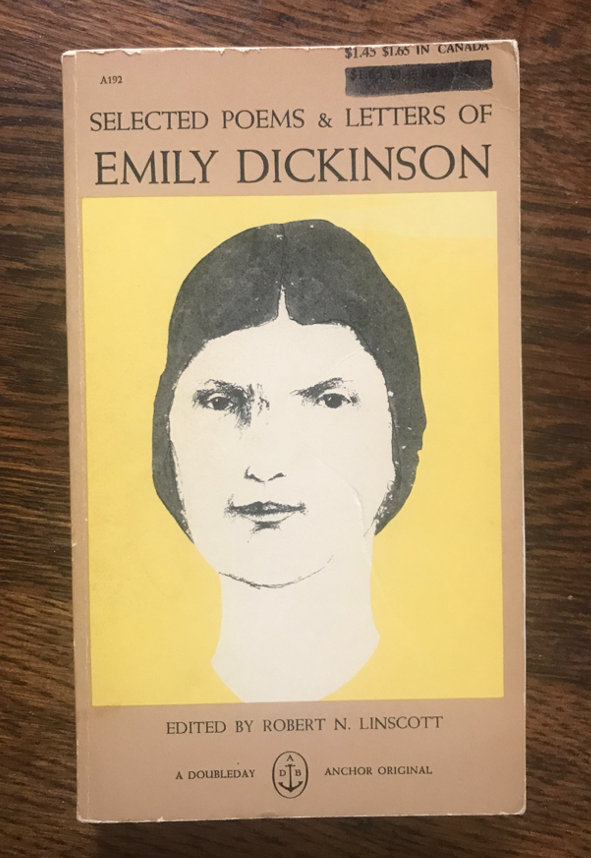

This selection of Emily Dickinson’s poems and letters has typography only by Edward Gorey.

-

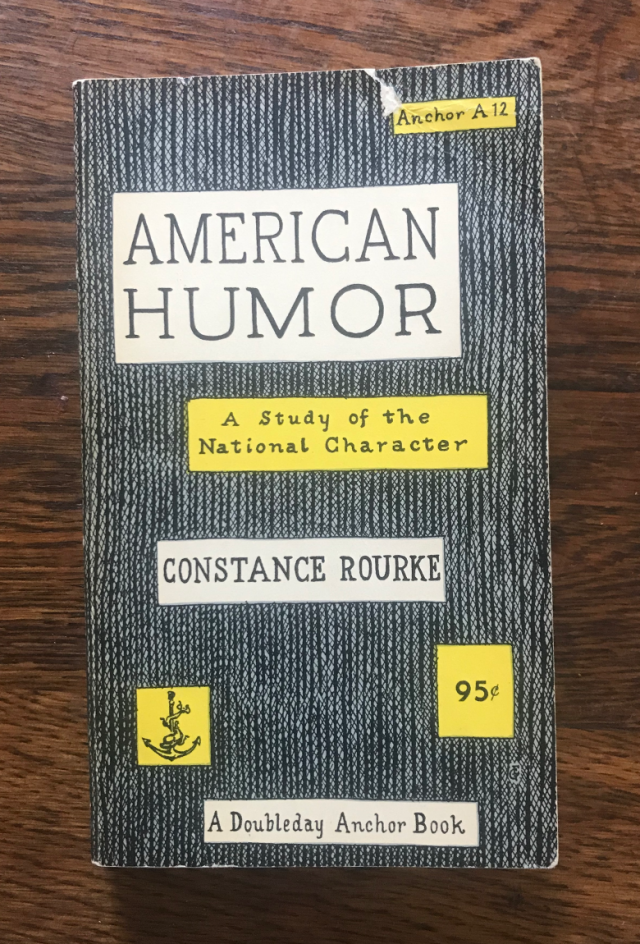

A neglected classic on humor and the national character by Constance O’Rourke. Joke’s on us. Cover design suitably dark, yet playful, also by Gorey.

-

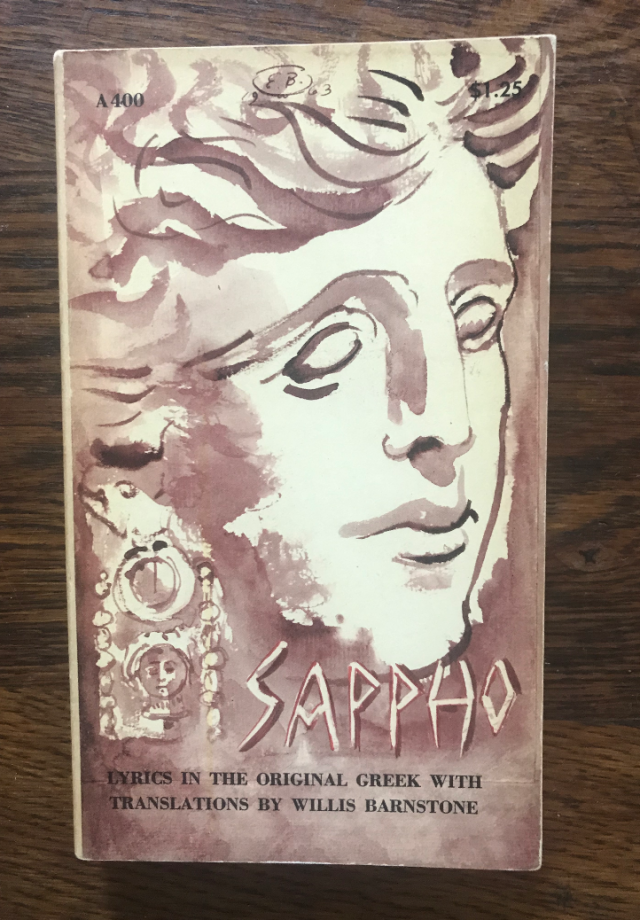

Mass market Sappho with the original Greek. What’s not to love!

-

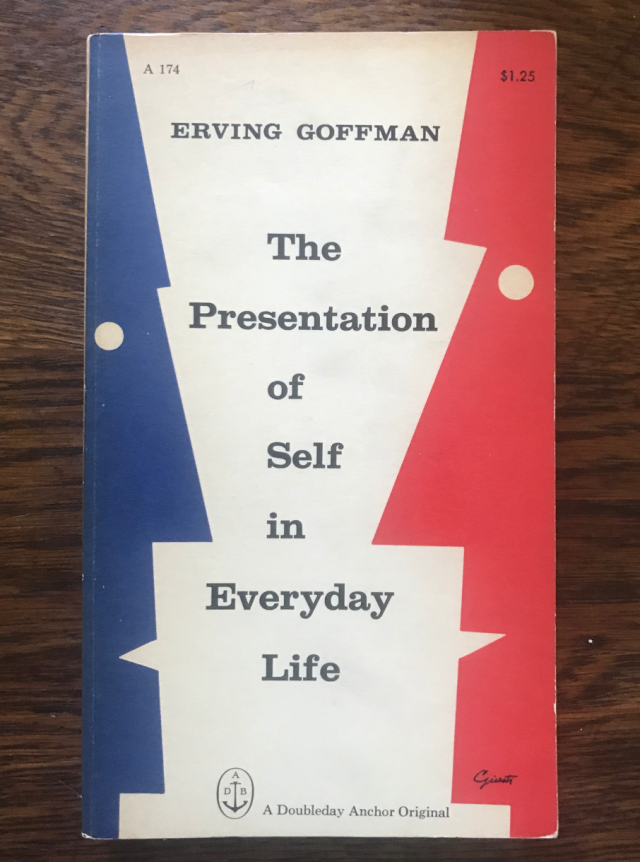

A Princeton University Press classic and perennial bestseller as reissued by Anchor.

-

A classic of sociology in a truly classic design with typography by Edward Gorey.

-

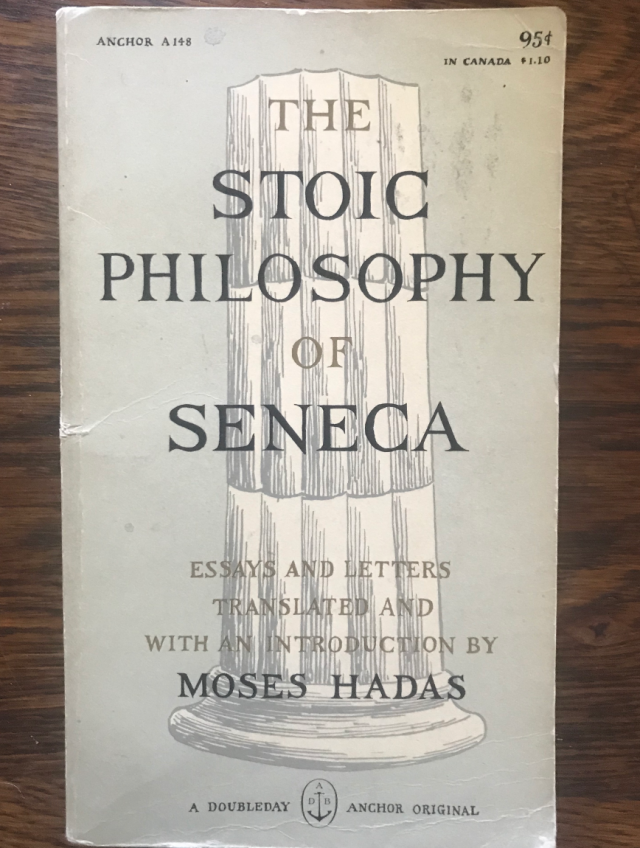

Gorey’s simple and perhaps not so subtle take on stoicism and Seneca.

-

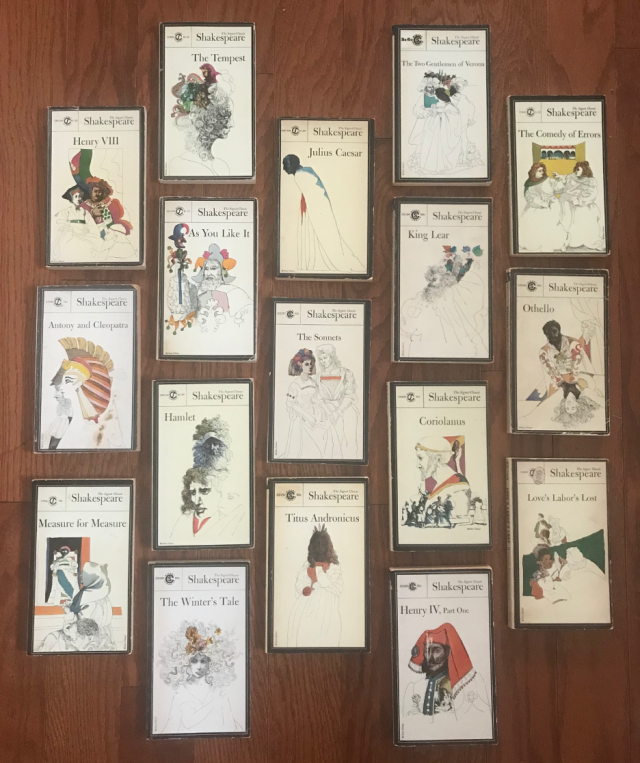

You may know him from his design of the world-famous “I Love NY” logo, but Milton Glaser also designed the covers for these Signet Shakespeare editions.

-

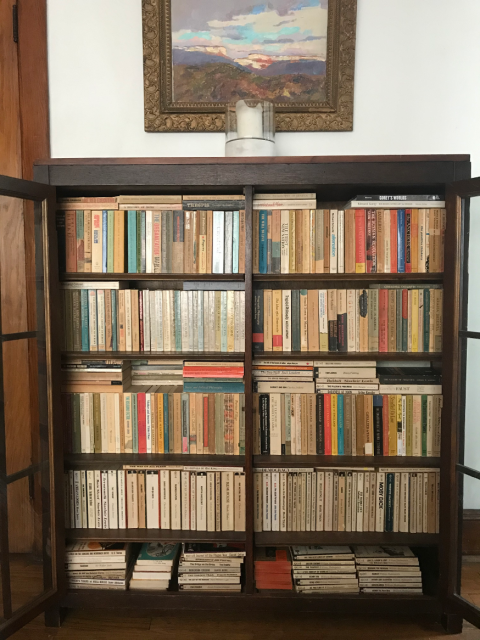

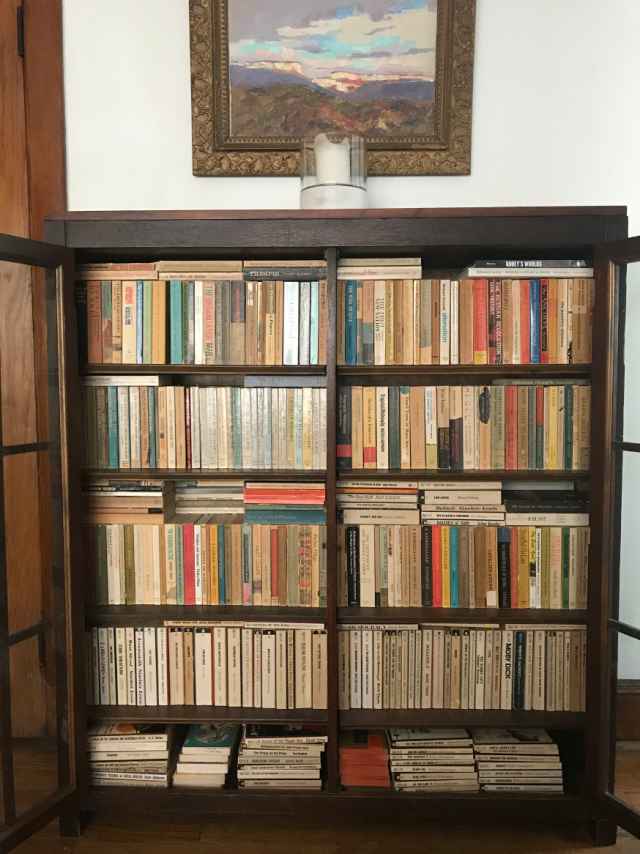

And finally, the non-hermetically sealed bookcase where I keep the collection. (Yes, they are two deep). I wish I could show you them all!

01 / 16

Rob Tempio is the Publisher for Philosophy, Political Theory, and the Ancient World at Princeton University Press.

Notes

[1] You can find a list of the books published under that imprint https://www.publishinghistory.com/anchor-books-doubleday.html, but beware, if you are completist, this list can easily become a checklist.

[2] There is a fine dissertation to be written, if it hasn’t been written already, about the impact these widely available and best-selling paperbacks such as Walter Kaufmann’s Existentialism, William Barrett’s Irrational Man, David Reisman’s The Lonely Crowd, and William Whyte’s The Organization Man had on those who would launch the 1960’s counter-culture. See Todd Gitlin’s history/memoir The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (Bantam, 1987, page 30), where he states that “Book marketing itself pried open a new cultural space…first Doubleday then other publishers began to publish serious non-fiction in paperback, so that…existentialism, the absurd, all manner of philosophy, history, and sociology…could circulate to the idea-hungry and college-bound.”

[3] I am reminded of the story told by a friend who worked for a wealthy socialite while getting her start in New York publishing. Shortly after 9/11, this socialite asked her to read and summarize Islam: A Very Short Introduction. I guess for some even the “very short” can be too long.

[4] Yes, today is Paperback Book Day. Somehow, despite my passion for the format, this was news to me to as well.