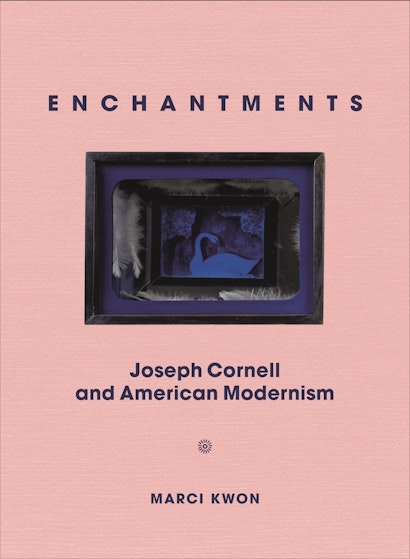

Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) is best known for his exquisite and alluring box constructions, which transform found objects into enchanted worlds that blur the boundaries between fantasy and the commonplace. Situating Cornell within the broader artistic, cultural, and political debates of midcentury America, this innovative and interdisciplinary account reveals enchantment’s relevance to the history of American modernism.

What led you to write this book?

MK: All of my writing begins with a question I feel called to answer. With this book, that question was: Why are some ways of being in the world taken less seriously than others? This question is deeply personal rather than merely academic.

Like many people, I love Cornell’s work. I love the delicacy and sparkle of his fantastical worlds. I love that, like me, he loves birds, ballet, bubbles, and movie stars. But when I look at his art, I also see ambivalence, melancholy, and fear beneath its veneer of lightness. I feel an unresolved tension between faith and doubt. What makes his work so compelling is this juxtaposition of the earthly and the transcendent; of the world’s lightness and its heaviness. Cornell also worked closely with filmmakers, poets, and fellow artists, including women and queer men. Yet the artist’s enchantment has led many to see him as reclusive, out of step with modernity, and detached from “real” life—in short, instinctual rather than intelligent. His work and reception offer a historical vantage onto the question of who, and what ways of being, are afforded the privilege of serious consideration.

What is enchantment, and how is it relevant to Cornell’s work?

MK: Enchantment is the experience of something that exceeds rational comprehension. It is associated with the divine, but can also refer to the metaphysical, the ideal, the occult, or the ineffable effects of poetry or art. As this range of definitions suggests, enchantment is a historical phenomenon: what is considered “outside” of rationality changes depending on cultural context.

German sociologist Max Weber used the phrase “disenchantment of the world” (die Entzauberung der Welt) to describe modernity. This influential idea positioned enchantment as antithetical to modernity, and made synonymous modernity and rational thought. Cornell’s example puts pressure on this formulation. The artist practiced Christian Science from the 1920s until the end of his life, an experience that shaped his enchantment—his conviction that the divine is present in world around us; that the past is not dead and gone, but can be felt in the present. Such beliefs are incompatible with the view of modernity as disenchanted; thus from this perspective, Cornell can only be seen as “eccentric” or “lost in dreams.” Following his work and reception allowed me to trace midcentury America’s shifting definitions and cultural attitudes toward enchantment, and the effects of these shifts on a range of artists, poets, and filmmakers.

What were some of these historical shifts?

MK: During the 1920s, the formative decade of Cornell’s practice, artists such as Alfred Stieglitz evinced a quasi-ironic interest in spirituality to critique the depredations of capitalism and industrial modernity. One can find a parallel to this in Surrealism, which saw the unconscious as a critique of contemporary civilization’s pretentions to rational thought. Surrealism’s migration to the United States in the late 1920s–30s shaped Cornell’s emergence as an artist, leading critics to describe his work as unconscious expression, an explanation that pained him to no end. Yet Surrealism’s popularity in the U.S. also offered Cornell visibility and financial opportunities, such graphic design commissions from Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar. Surrealist enchantment thus presented Cornell with a double-edged sword: its popularity allowed him to make a career and support his family, but it also contributed to the simplistic view of his practice that persists today.

Undoubtedly the most significant shift in cultural attitudes toward enchantment occurred with the rise of Fascism in Europe in the 1930s and early 40s. Watching with horror from the United States, many asked themselves, how could this happen? The global rightward turn of the past decade has made this question all too familiar. Many blamed the rise of Fascism on irrationality itself, for how else to explain the purportedly “mindless” adherence to the whims of a charismatic dictator? As witnesses and survivors of the genocidal regime, German philosophers Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer offered a more nuanced consideration of this question. In the mid-1940s, they diagnosed disenchantment—the ostensible progress of Western society from irrational to rational—as itself a pernicious myth. Yet the broader association of Fascism and irrationality persisted (even, to a certain extent, within Adorno and Horkheimer’s thinking), leading enchantment to be cast as politically suspect.

Although this book focuses on Cornell, you also discuss many of his interlocutors. How do their stories intersect with Cornell’s?

MK: Part of what drew me to Cornell was a feeling that he might help me piece together a genealogy of cultural figures working in midcentury New York whose connections I always sensed, but couldn’t fully articulate. Cornell worked closely with poets Mina Loy and Marianne Moore, and was admired by John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara. He hired experimental filmmakers Rudy Burkhardt, Larry Jordan, Stan Brakhage, and Ken Jacobs as assistants. He worked for Marcel Duchamp, showed with Jackson Pollock, and was for a time close friends with Robert Motherwell. His graphic design work led him to collaborate with ballet impresario Lincoln Kirstein, as well as Charles Henri Ford and Parker Tyler, founders of the insurgent Surrealist little magazine View and authors of the legendary early queer novel The Young and Evil. And in the book’s epilogue, I discuss three artists from the postwar period who explicitly drew on and critiqued Cornell’s example: Robert Rauschenberg, Betye Saar, and Carolee Schneemann.

Although most these figures did not share Cornell’s precise definition of enchantment, many found inspiration in his ability to find meaning in the everyday, the common. As Parker Tyler wrote in 1939, with Cornell as our guide, “We would transform our world into a more livable one, a kinder and more solidly glamorous one.”

Marci Kwon is assistant professor of art and art history at Stanford University. She lives in Palo Alto, California.