I have always been an experimental biologist. Ants have been my life, and I have tracked their behavior from above ground for over fifty years. I’ve learned to determine their territory, their selection of nest sites and their reproductive habits and how they divide up their enormous and impressive workload, all from experiments above my terra firma. Of course I knew something about the bulk of their life spent underground. But, my exploration of ant nest architecture was a sideline until rather late in my career when it became almost an obsession.

This was not an established field of research and there were very few off-the-shelf solutions to the problems I encountered. By trial and error, step by hesitant step, I developed methods for making what was invisible below ground visible, until I was sucked in by the beauty and complexity of what my efforts revealed. Some nests were so deep that when I stood in the bottom of the hole, my head was only halfway up the wall of the pit. The majority of the nests were deeper than I was tall, and required me to move 2 to 4 tons of sand out (and back in when finished). I was challenged by the immense labor required to do this, and resigned myself to clothes and socks full of sand!

Ant Architecture explores many related topics, and reveals what astounding feats the ants perform in excavating their nests. As an example, colonies of the Florida harvester ant with 7 thousand worker ants that together weigh less than an ounce move more than 16 lb of soil to create a nest with a volume of more than 2 gallons. By the time the ants have completed their excavation, the sum of the upward trips of sand-carrying ants is more than 400 miles, approximately the distance from New York to Cleveland. They carry out this amazing labor in the dark and without a leader, creating an underground space of beauty and organization. To add to this impressive feat, the colony moves about once a year, creating the new nest and moving into it in 4 to 6 days.

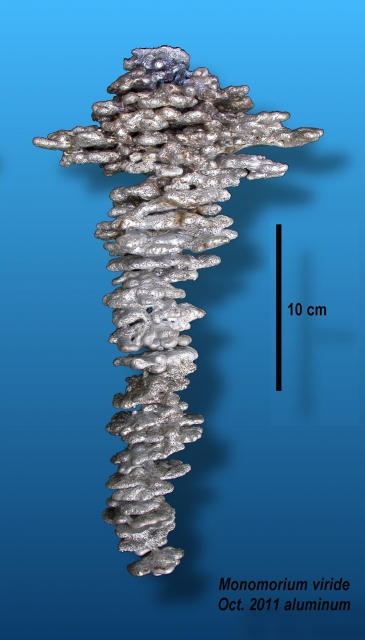

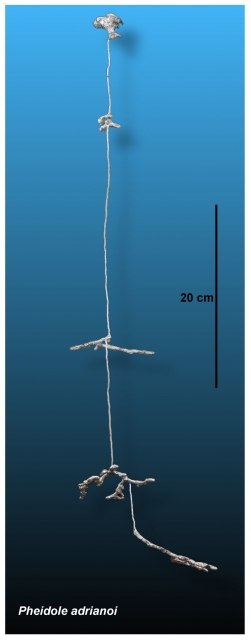

When digging up a nest, I exposed every chamber, one at a time, collected its contents and traced its outline. Such data reveal much about how the ants locate their various functions within the nest, and show that workers of most species arrange themselves by their age, which in turn is related to their duties. The youngest workers deep in the nest take care of the brood and queen and move upward as they age taking on more general nest duties. Only the oldest workers leave the nest to forage, and are always found in the very top chambers, ready for the dangerous chore of collecting food for the colony. Still, digging up colonies with a shovel can only produce a shadowy representation of the complete 3-dimensional spaces that the ants have created underground. To reveal this true shape, it became necessary to fill the hollow spaces with a casting material, then to excavate to the nest cast to reveal the nest architecture in all its complexity. The objects thus created have an inherent beauty and charm, with tremendous variation in size and architecture across the species of ants. Because the largest ants are more than 1000-fold as large as the smallest, it isn’t surprising that ant nests also range hugely in size. As the numbers of individuals in a colony vary wildly, from hundreds to many millions of workers, their nests range from simple shafts with a few chambers to huge, complex underground cities. Add to this, the evolutionary diversity of the 14,000 species of ants, each with particular life habits and biology, and the range of nest sizes and architectural variation is inevitable, as is the aesthetic beauty. Two of my favorites are shown below. Many more equally attractive nests are illustrated in Ant Architecture, and hopefully, many more will be brought to light in the future.

The job of a biologist is to make sense of bewildering patterns, and the main principle for doing this is that of evolution. No ant species re-invents the architecture of its nest each time it builds one. Rather, both the ant species and their nests have evolved over about 100 million years since the first ant dug the first nest—a simple, vertical shaft and one to several small, horizontal chambers. All modern ant nests are modifications, enlargements, elaborations and multiplications of this ancestral nest.

No matter the architecture, the ants create their nests through the wonder of self-organized labor of dozens to millions of workers, and they do so in the dark and without a leader. How this happens is still a central mystery, though a few principles are dimly visible. Ant Architecture is a down payment on these discoveries.

Walter R. Tschinkel is professor emeritus of biological science at Florida State University and a world authority on ant biology. He is the author of The Fire Ants. He lives in Tallahassee, Florida.