This incisive undergraduate textbook emphasizes the institutional sources of presidential power and executive governance, enabling students to think more clearly and systematically about the American presidency at a time when media coverage of the White House is awash in anecdotes and personalities. William Howell offers unparalleled perspective on the world’s most powerful office, from its original design in the Constitution to its historical growth over time; its elections and transitions to governance; its interactions with Congress, the courts, and the federal bureaucracy; and its persistent efforts to shape public policy. Comprehensive in scope and rooted in the latest scholarship, The American Presidency is the perfect guide for studying the presidency at a time of acute partisan polarization and popular anxiety about the health and well-being of the republic.

- Focuses on the institutional structures that presidents must navigate, the incentives and opportunities that drive them, and the constraints they routinely confront

- Shows how legislators, judges, bureaucrats, the media, and the broader public shape the contours and limits of presidential power

- Encourages students to view the institutional presidency as not just an object of study but a way of thinking about executive politics

- Highlights the lasting effects of important historical moments on the institutional presidency

- Enables students to grapple with enduring themes of power, rules, norms, and organization that undergird democracy

William G. Howell is the Sydney Stein Professor in American Politics at the University of Chicago, where he is director of the Center for Effective Government and cohost of Not Another Politics Podcast. He has taught courses on the American presidency for more than twenty years, and his many books include Presidents, Populism, and the Crisis of Democracy; The Wartime President; and Power without Persuasion (Princeton).

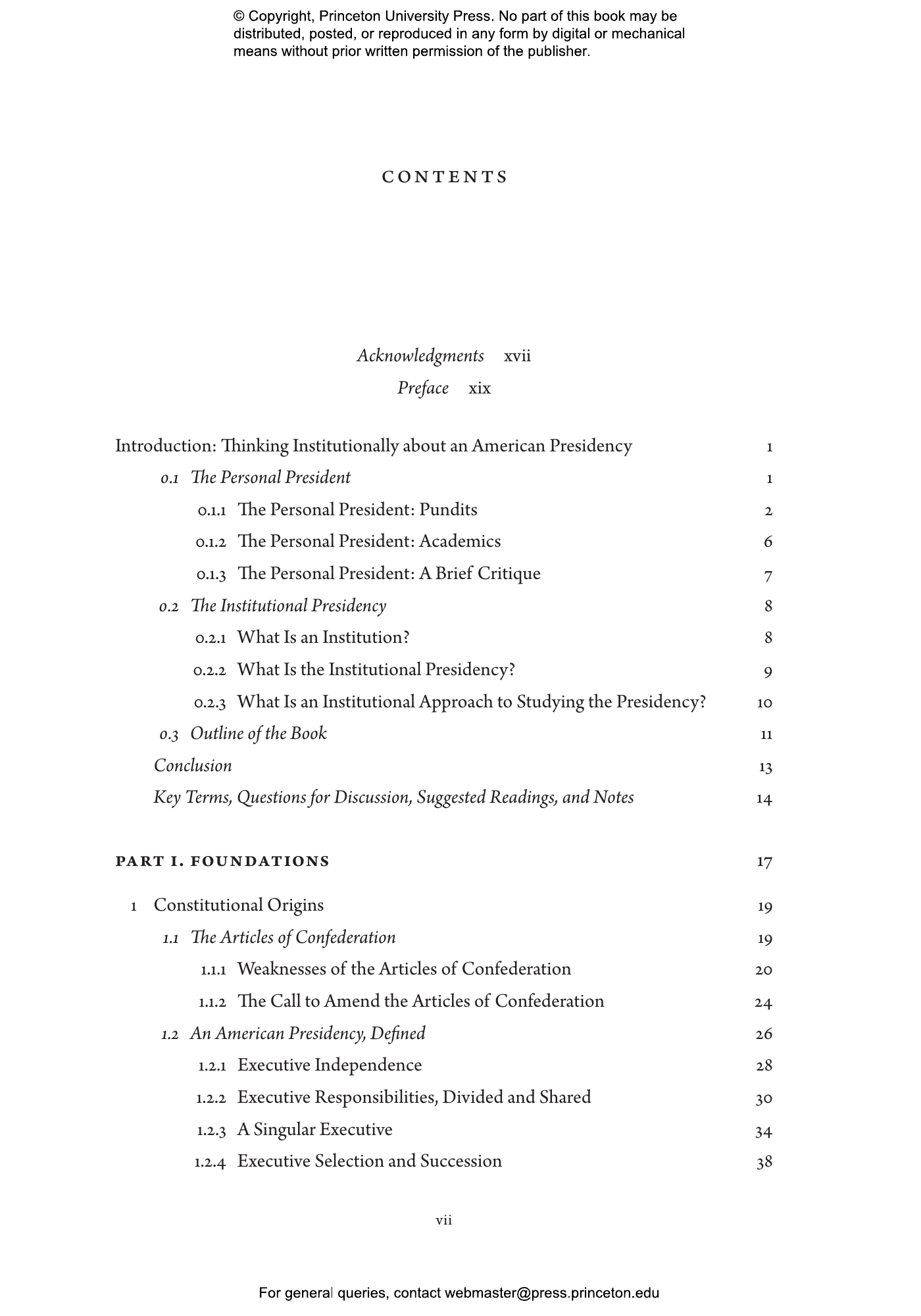

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

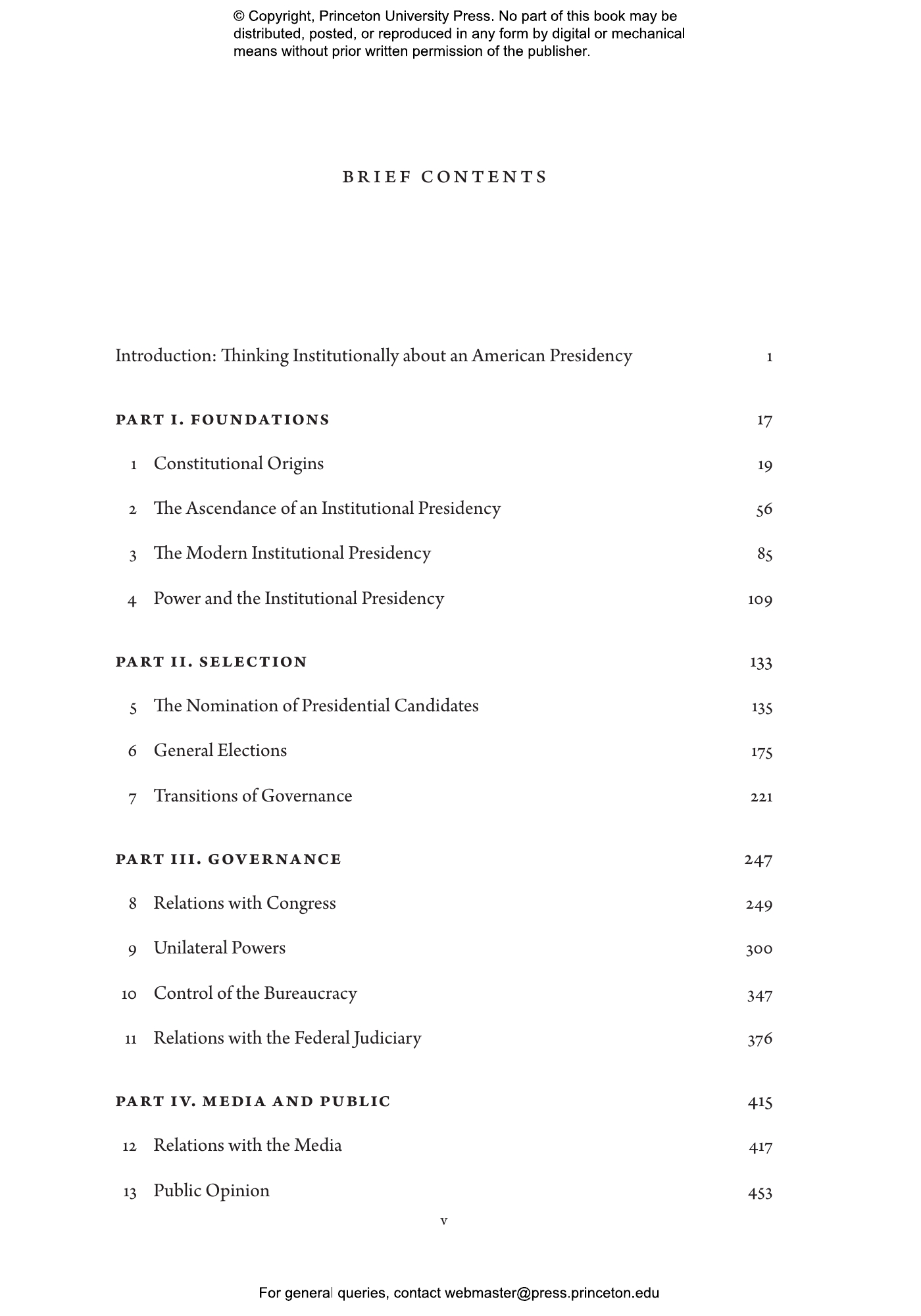

- Introduction: Thinking Institutionally about an American Presidency

- 0.1 The Personal President

- 0.1.1 The Personal President: Pundits

- 0.1.2 The Personal President: Academics

- 0.1.3 The Personal President: A Brief Critique

- 0.2 The Institutional Presidency

- 0.2.1 What Is an Institution?

- 0.2.2 What Is the Institutional Presidency?

- 0.2.3 What Is an Institutional Approach to Studying the Presidency?

- 0.3 Outline of the Book

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- Part I. Foundations

- 1 Constitutional Origins

- 1.1 The Articles of Confederation

- 1.1.1 Weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation

- 1.1.2 The Call to Amend the Articles of Confederation

- 1.2 An American Presidency, Defined

- 1.2.1 Executive Independence

- 1.2.2 Executive Responsibilities, Divided and Shared

- 1.2.3 A Singular Executive

- 1.2.4 Executive Selection and Succession

- 1.3 Textual Meanings

- 1.3.1 Ambiguity

- 1.3.2 Silence

- 1.3.3 Context and Meaning

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 2 The Ascendance of an Institutional Presidency

- 2.1 Nineteenth-Century Presidents

- 2.2 The Progressive Era and Institutional Change

- 2.2.1 Theodore Roosevelt’s Stewardship

- 2.2.2 Woodrow Wilson: Progressivism Continued

- 2.3 Scientific Management and Institutional Change

- 2.3.1 A Brief, and Ultimately Discredited, Conservative Resurgence

- 2.3.2 Franklin Delano Roosevelt: Engineering a New American State

- 2.4 War and Institutional Change

- 2.4.1 World War I

- 2.4.2 World War II

- 2.5 The Long Civil Rights Movement and Institutional Change

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 3 The Modern Institutional Presidency

- 3.1 The Basic Architecture

- 3.1.1 The Executive Office of the President

- 3.1.2 The Cabinet

- 3.1.3 Independent Agencies and Government Corporations

- 3.2 Partners to the President

- 3.2.1 The Office of the Vice President

- 3.2.2 The Office of the First Spouse

- 3.3 For Any Policy, a Crowded Field of Institutions

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 4 Power and the Institutional Presidency

- 4.1 What Is Political “Power”?

- 4.2 Great Expectations

- 4.3 Power and Executive Action

- 4.4 Evaluating the President’s Powers

- 4.4.1 Constitutionally Enumerated Powers

- 4.4.2 Additional Sources of Power

- 4.5 Constraints and Backlash

- 4.6 An Enduring Interest in Power

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

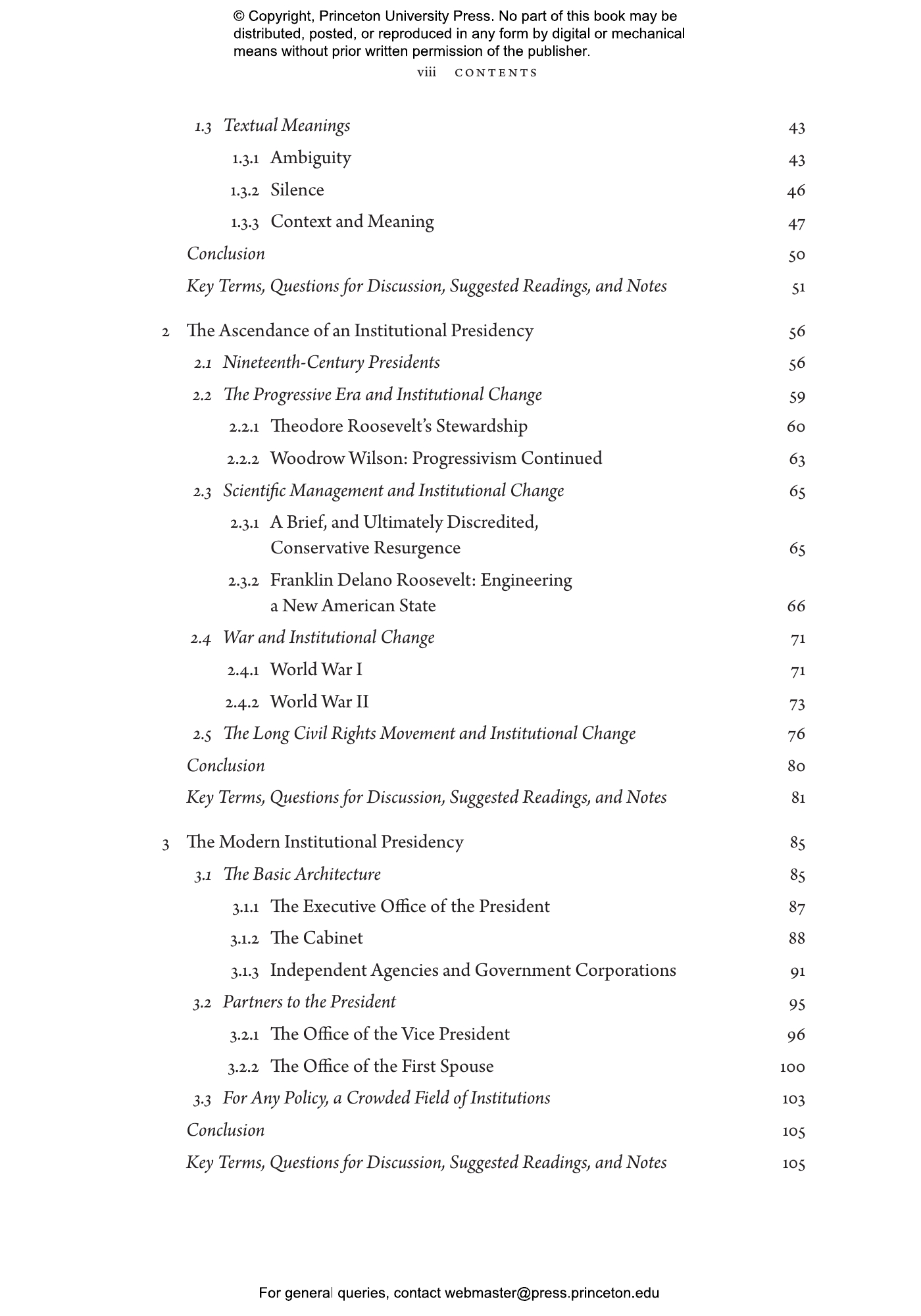

- Part II. Selection

- 5 The Nomination of Presidential Candidates

- 5.1 Presidential Nominations: Institutions of the Past

- 5.1.1 King Caucus: 1796–1824

- 5.1.2 National Party Conventions, Local Control: 1832–1912

- 5.1.3 Trial-and-Error Primaries: 1912–1968

- 5.2 Presidential Nominations: The Modern Institution

- 5.2.1 The Pool of Primary Candidates

- 5.2.2 Open Primaries, Closed Primaries, and Caucuses

- 5.2.3 The Primary Electorate

- 5.2.4 The Nominating Season

- 5.2.5 Allocation of Delegates

- 5.2.6 Party Conventions

- 5.3 Institutional Biases in Candidate Selection

- 5.3.1 The Early State Advantage

- 5.3.2 The Influence of Parties

- 5.4 Campaign Spending

- 5.4.1 Money Matters

- 5.4.2 Citizens United v. FEC (2010)

- 5.5 Selecting a Running Mate

- 5.5.1 Balancing the Ticket

- 5.5.2 Battleground Magnates

- 5.5.3 Descriptive Representation

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 6 General Elections

- 6.1 Presidential Electorates

- 6.1.1 Tacking to the Ideological Middle

- 6.1.2 Swing States

- 6.1.3 Appealing to a Changing National Electorate

- 6.2 The Economy and the Presidential Vote

- 6.2.1 Pocketbook versus Sociotropic Voting

- 6.2.2 Implications for Candidate Strategy

- 6.3 The Marginal, but Consequential, Effects of Campaigns

- 6.3.1 Campaign Advertising

- 6.3.2 Presidential Debates

- 6.3.3 Campaign Scandals

- 6.3.4 October Surprises

- 6.4 Declaring a Winner

- 6.4.1 Counting Votes, Certifying Elections

- 6.4.2 Contested Elections

- 6.4.3 Democratic Vulnerabilities

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 7 Transitions of Governance

- 7.1 Planning the Transition

- 7.1.1 Pre-Election Planning

- 7.1.2 Personnel Decisions

- 7.1.3 Prepping a Policy Agenda

- 7.2 Managing Campaign and Party Operatives

- 7.2.1 Campaign Operatives

- 7.2.2 When Campaigners Don’t Help in Governance

- 7.2.3 Intraparty Rivals

- 7.3 Soliciting Help from the Outgoing Administration

- 7.3.1 Responding to Events in Real Time

- 7.3.2 Information Transfers

- 7.3.3 When Cooperation Proves Difficult

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

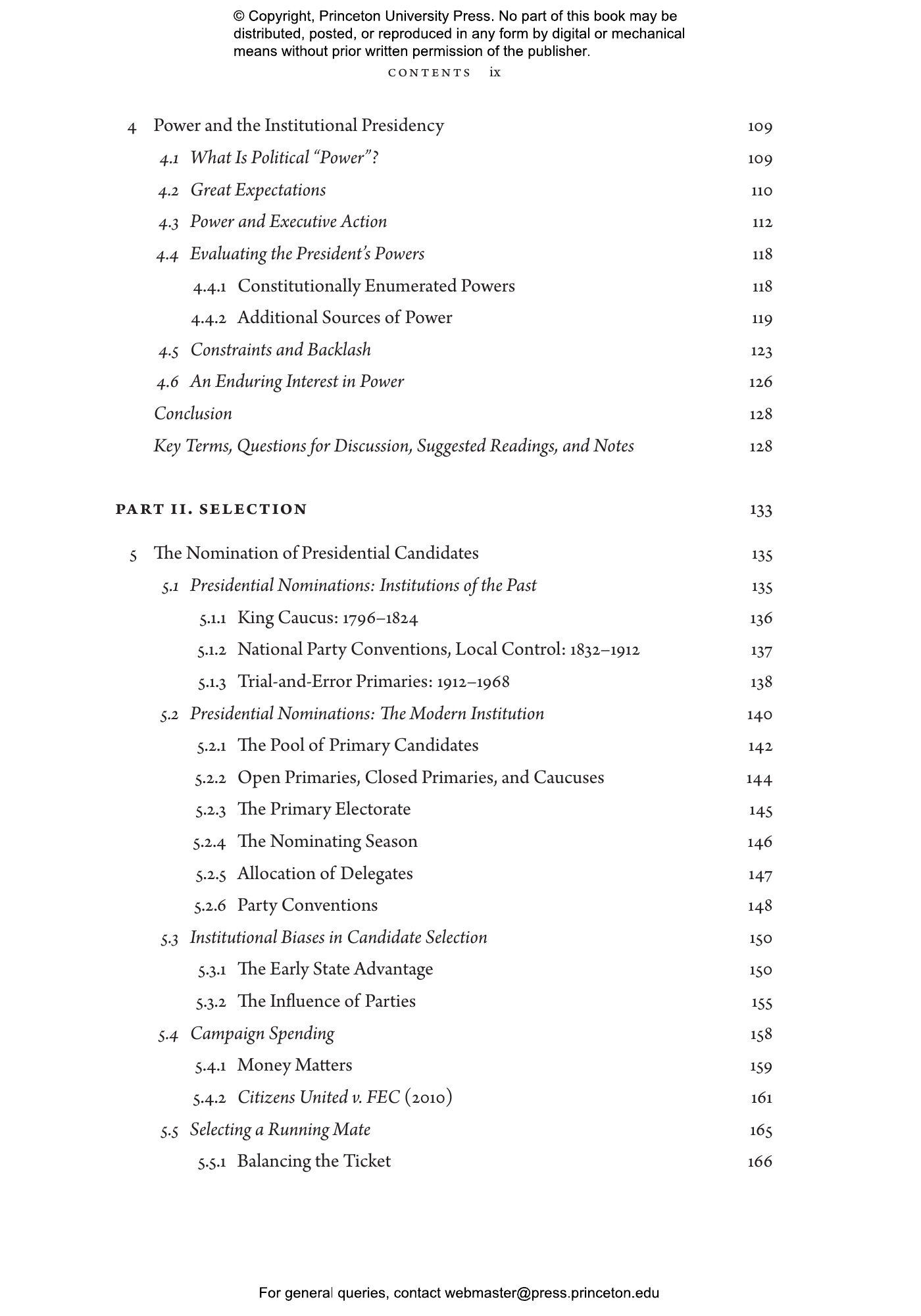

- Part III. Governance

- 8 Relations with Congress

- 8.1 Power through Persuasion

- 8.1.1 An Archetypal Case: LBJ and the Civil Rights Act

- 8.1.2 The Limits of Persuasion

- 8.1.3 The Subjects of Persuasion

- 8.2 Predicting Legislative Success and Failure

- 8.2.1 Timing

- 8.2.2 Unified versus Divided Government

- 8.2.3 Party Polarization

- 8.2.4 Nationalized Politics

- 8.2.5 Foreign versus Domestic Policy

- 8.3 Veto Politics

- 8.3.1 Vetoes and Overrides

- 8.3.2 Veto Threats and Concessions

- 8.3.3 The Line-Item Veto

- 8.4 Appropriations

- 8.4.1 Proposing a Budget: Ex Ante Influence

- 8.4.2 Manipulating the Budget: Ex Post Influence

- 8.4.3 Impoundment Authority

- 8.5 Battles over Institutional Power

- 8.5.1 Congressional Delegations of Authority

- 8.5.2 Congressional Oversight

- 8.5.3 Attempting to Dismantle Presidential Power: The Bricker Amendment

- 8.6 Removing the President from Office

- 8.6.1 The Purposes of Impeachment

- 8.6.2 Johnson’s Impeachment

- 8.6.3 Nixon’s Resignation

- 8.6.4 Clinton’s Impeachment

- 8.6.5 Trump’s First Impeachment

- 8.6.6 Trump’s Second Impeachment

- 8.6.7 The Politics of Impeachment

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 9 Unilateral Powers

- 9.1 Power without Persuasion

- 9.1.1 Unilateral Directives

- 9.1.2 Unilateral Decisions

- 9.1.3 Trends in Unilateral Activity

- 9.2 The Legal Basis for Unilateral Action

- 9.2.1 Constitutional Authority

- 9.2.2 Statutory Authority

- 9.2.3 Emergency Powers

- 9.3 Institutional Checks on Unilateral Action

- 9.3.1 Reporting Requirements

- 9.3.2 Budgets

- 9.3.3 Bureaucratic Resistance

- 9.3.4 Presidents Checking Presidents

- 9.3.5 The Public as a Final Line of Defense?

- 9.4 The Demonstration of Presidential Influence

- 9.4.1 The Strategic Exercise of Unilateral Powers

- 9.4.2 Implementing Public Policy

- 9.4.3 Enhanced Control over the Bureaucracy

- 9.4.4 Getting onto the Legislative Agenda

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 10 Control of the Bureaucracy

- 10.1 Administrative and Political Problems

- 10.1.1 The Long History of Administrative Reform

- 10.1.2 Enter Politics

- 10.1.3 Whose Bureaucracy?

- 10.2 Politicization

- 10.2.1 What Politicization Looks Like

- 10.2.2 Opportunities for Politicization

- 10.2.3 When Do Presidents Politicize?

- 10.2.4 Politicization’s Close Cousin: Patronage

- 10.3 Centralization

- 10.3.1 White House Staff

- 10.3.2 Policy Czars

- 10.3.3 When Do Presidents Centralize?

- 10.4 Bureaucratic Redesign: Cutting, Restructuring, and Creating Anew

- 10.5 Downsides, Limitations, and Scandal

- 10.5.1 Downsides

- 10.5.2 Limitations

- 10.5.3 Scandal

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 11 Relations with the Federal Judiciary

- 11.1 Foundations of Judicial Decision Making

- 11.1.1 Applying Legal Norms and Principles

- 11.1.2 Ideological Convictions

- 11.1.3 Concerns about Institutional Legitimacy

- 11.1.4 In Practice, More than One Motivation

- 11.2 Implications for Cases Involving the President

- 11.2.1 Political Question Doctrine

- 11.2.2 The “Zone of Twilight”

- 11.2.3 Chevron Deference

- 11.3 Taking on the President

- 11.3.1 Challenging an Executive’s Special Privileges

- 11.3.2 Challenging an Executive’s Newly Acquired Powers

- 11.3.3 Suing the President

- 11.3.4 Striking Down a President’s Policy

- 11.4 All the President’s Lawyers

- 11.4.1 Lending Advice and Legal Cover

- 11.4.2 Representing the President in the Federal Judiciary

- 11.5 Judicial Nominations

- 11.5.1 Appointing Co-Partisans to the Bench

- 11.5.2 Selecting Judges with Expansive Views of Presidential Power

- 11.5.3 The Politics of District and Appellate Court Nominations

- 11.5.4 Increasingly Partisan Supreme Court Nominations

- 11.5.5 Eroding Norms of Consideration

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- Part IV. Media and Public

- 12 Relations with the Media

- 12.1 Foundations of the Plebiscitary Presidency

- 12.2 New Media Technologies

- 12.2.1 Radio

- 12.2.2 Television

- 12.2.3 Digital Media

- 12.3 The Modern Media Landscape

- 12.3.1 An Increasingly Polarized Viewing Audience?

- 12.3.2 Political Disinformation

- 12.4 Institutionalizing Presidential Relations with the Press

- 12.4.1 The President’s Press Operation

- 12.4.2 The White House Press Corps

- 12.5 Navigating the Media Landscape

- 12.5.1 Constraining the Press

- 12.5.2 Managing Information Flows

- 12.5.3 Working around the Press

- 12.6 The Media: Watchdog or Lapdog?

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 13 Public Opinion

- 13.1 Foundations of Public Opinion

- 13.1.1 Party Membership

- 13.1.2 Issue Positions

- 13.1.3 Political Elites

- 13.1.4 Economic Evaluations

- 13.2 The Shape of Public Opinion

- 13.2.1 General Decline

- 13.2.2 Rally Effects

- 13.3 Taking Stock of Public Opinion

- 13.3.1 White House Polls

- 13.3.2 Putting Polls (and the Public) to Use

- 13.3.3 The Measured Significance of Public Opinion

- 13.4 Influencing Public Opinion

- 13.4.1 Evaluations of Presidential Policies

- 13.4.2 Evaluations of Presidents

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

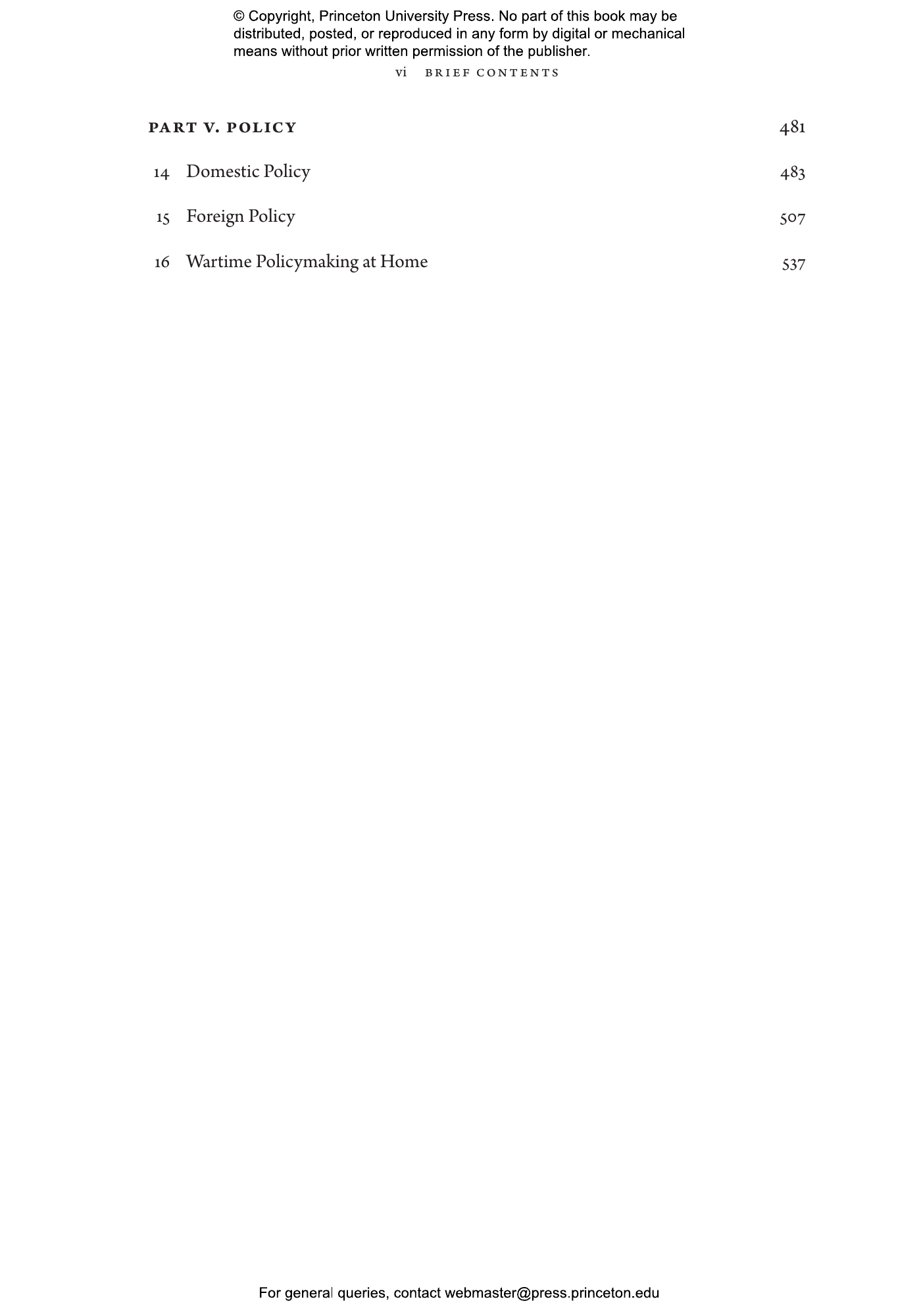

- Part V. Policy

- 14 Domestic Policy

- 14.1 A National Outlook

- 14.1.1 Case Study: Trillions in Pandemic Relief

- 14.2 Power Considerations

- 14.2.1 Case Study: Budgetary Powers

- 14.3 Legacy

- 14.3.1 Case Study: Harry Truman and Civil Rights

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 15 Foreign Policy

- 15.1 Presidential Advantages in Foreign Policy

- 15.1.1 Military Capabilities

- 15.1.2 Economic Considerations

- 15.2 International Constraints on Foreign Policymaking

- 15.2.1 Alliances

- 15.2.2 International Law

- 15.3 Domestic Constraints on Foreign Policymaking

- 15.3.1 Formal Congressional Checks on Presidential Foreign Policymaking

- 15.3.2 Informal Congressional Checks on Presidential Foreign Policymaking

- 15.3.3 Intrabranch Checks on Presidential Foreign Policymaking

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- 16 Wartime Policymaking at Home

- 16.1 War and Presidential Power: A Brief Intellectual History

- 16.2 Evidence That Wars Expand Presidential Influence

- 16.2.1 Wartime Appropriations

- 16.2.2 Congressional Voting in War and Peace

- 16.3 Three Cases of Wartime Policymaking at Home

- 16.3.1 World War II

- 16.3.2 The Vietnam War and Johnson’s Great Society

- 16.3.3 September 11, 2001, and Thereafter

- Conclusion

- Key Terms, Questions for Discussion, Suggested Readings, and Notes

- Appendix A

- Appendix B

- Appendix C

- Glossary

- Index

"A valuable reference for anyone interested in the highest political office in the land. . . . this textbook offers a more incisive and balanced examination of this elected office."—Jerry D. Lenaburg, New York Journal of Books

“William Howell is a superstar among presidency scholars, and he has written an enlightening tour de force of a textbook—applying an institutional perspective that brings coherence and new insights to a full range of presidential topics, from policymaking to elections to public opinion to unilateral action and more. An incomparable opportunity for students to learn from the very best.”—Terry Moe, Stanford University

“Individual presidents cast an oversized shadow. For admirers and critics alike, they are the focal point of American politics and dominate the political stage. Yet presidential decisions and actions are products of broader institutional forces, both within the executive branch and the larger domestic and international environment in which presidents operate. The American Presidency teaches students to think institutionally. In so doing, Howell both provides students the background essential to understanding the presidency and equips them with the analytical tools to assess independently the most pressing questions in contemporary presidential politics.”—Douglas L. Kriner, Cornell University

“Howell argues that the presidency is best understood as an institution rather than an array of personalities. With his discerning and distinctive point of view, Howell writes an ideal text—one that covers all the major topics and approaches to the presidency and, at the same time, offers a consistent argument. This superb text is designed to teach students to think like political scientists while learning the history of this institution and issues of political concern today.”—Jeffrey K. Tulis, University of Texas at Austin

“Howell provides an invaluable primer for students to understand how presidents may thrive in an institutionalized structure of shared powers, and why established executive processes and ethics-based practices are essential to the continuance of representative democracy. This is a must-read volume, including for undergraduates aiming for careers in public service.”—José D. Villalobos, University of Texas at El Paso

“This comprehensive book systematically examines the American presidency from an institutional perspective. Using the conceptual lens of incentives that guide institutional behavior, it analyzes the origins of the presidency, presidential selection, governance, public relations, and policymaking. Thoughtful and engaging, The American Presidency is instructive for both students and scholars of the presidency and American politics.”—Meena Bose, Hofstra University