Before the story goes on, some ground needs to be cleared. What is conservatism? What is this a story of? There are no knockdown facts here. The terms in play are tricky, but “what is conservatism?” is not about labels or meanings. The question bears on conservatism’s character and its kind, which have to be understood historically.

If you ask what kind of thing conservatism is, you will hear that it is a party-political family, counsel of government, philosophy of society, mouthpiece of the haves, voice of all classes, unexalted picture of humankind, or universal human preference for the steady and familiar against the changeable and strange. Each answer catches some aspect of conservatism. All are partial. Conservatism as understood here is a tradition or practice of politics. As with any practice, that involves three things. Conservatism has a history, it has participants in the practice—politicians, thinkers, backers, voters—and it has an outlook to guide them. Neither who conservatives are nor what they think can be put into a phrase or formula. Its practice is complex, but that is poor reason to stop before the story starts.

In the early nineteenth century, like liberals, their first opponents, conservatives faced new social conditions previously unimagined. Although their social and intellectual roots were old and deep, the scale and pace of change was disorienting. After creeping along for centuries, populations and economies had suddenly exploded in growth. Technical innovation was altering settled forms of life. Movement from country to town freed people from old authorities and customary ties. People who read and argued about politics were no longer counted in the thousands but hundreds of thousands, soon millions. Money was spent to make things that created yet more money. Capitalist modernity, in short, was turning economic methods, social patterns, and people’s outlooks upside down. It enriched and impoverished, empowered and disempowered, shuffled social ranks, created high expectations, and reframed ethical norms. In this exciting, destabilizing new condition of society, politics had to rethink itself. Liberalism and conservatism were born.

Liberals, to schematize, embraced capitalist modernity. Conservatives responded by opposing the liberal embrace. The first liberals welcomed capitalism and critical thought, the twin turbines of modern change. Liberals favored freer markets, moveable labor, and the self-generative force of money. They embraced religious indifference and social and cultural diversity, as well as the constructive power of disagreement. The first conservatives defended closed markets and stable patterns of life while fearing the solvent powers of finance. They stressed social unity, shared faith, and common loyalties. Liberals saw themselves as opening up society, releasing energies, and letting people go. Conservatives saw liberals as breaking up society, spreading disorder, and leaving people bewildered. Liberalism offered experiment and endeavor. Conservatism promised certainty and security. Without having to claim that liberals caused capitalist modernity, conservatives blamed liberals for embracing capitalist modernity. It quickly became for conservatives a liberal modernity.

Conservatives linked liberals with blind encouragement of change, just as liberals linked conservatives with blind resistance to change. By the 1830s, when two Baden liberals began publishing their massive study of contemporary politics, the Staatslexikon, liberals were described in it as the “party of movement,” conservatives as the “party of resistance or standstill.” Conservatives, by implication, were obstructionists. Conservatives turned the imputation around: liberals were destructionists; they stood for disorder and insecurity, whereas conservatives stood for order and stability. Both in fact were looking for social order but did not think of it in the same way.

Were politics chess, liberals had white; they moved first. Conservatives had black; they countered liberalism’s opening moves. In time, the initiative changed hands. Conservatives, who began as anti-moderns, came to master modernity, for the right was in telling ways the stronger contestant. It spoke for the powers of wealth and property—first, land against industry and finance, then for all three, and soon for small property as well as large. Conservatism, in addition, would rely well into the twentieth century on the organs of state and on society’s many corps—law, religion, armed forces, universities—which tended to a stand-pat conservatism in the everyday, prepolitical sense of wanting tomorrow to be like today and not forever changing the furniture. Conservatives overcame fears of political democracy and by the early twentieth century were regrouping—in ascending order of coherence, in Germany, France, the United States, and Britain—as formidable electoral powers.

Those triple advantages—the backing of wealth, institutional support, and electoral reach—helped the right prevail at the liberal democratic game. Puzzling as it sounds, conservatism’s ultimate reward for compromising with liberal democracy was domination of liberal democracy. Though cast by the left as politicians of the past, the right became the leading force of modern times, as its party-political record in office confirms. After 1914 in the France’s Third Republic (1870–1940), Republicans (right-wing liberals) traded office (often in coalition) with Radicals (left-wing liberals), keeping socialists and communists at bay. A similar pattern followed in the Fourth Republic (1944–58). In over sixty years of the French Fifth Republic, the president was on the right in more than thirty-nine, on the left in twenty (and those presidents—François Mitterrand and François Hollande, were of the palest, most center-minded left), with a centrist, Emmanuel Macron, making up the remainder. In Britain, the twentieth century was a “Conservative century” in terms of office. From 1895 to 2020, the Tories governed alone or were the majority party in coalition governments for 81 of 126 years. The right’s dominance in the United States was harder to spot. In thirty-one presidential elections (1896–2016), Republicans won seventeen, Democrats fourteen. Republicans controlled the Senate for only fifty-four years, against the Democrats’ sixty-eight, and only fifty-two against seventy in the House. On another measure of dominance, Republicans held the White House and both houses of Congress for forty-four years, against forty for the Democrats. That seeming balance masked the fact that a solid white South returned conservative, segregationist Democrats until the 1970s. If control of the national agenda is the test, reform Democrats framed the political argument only for a time after 1913 and then again from the 1930s to the 1960s.

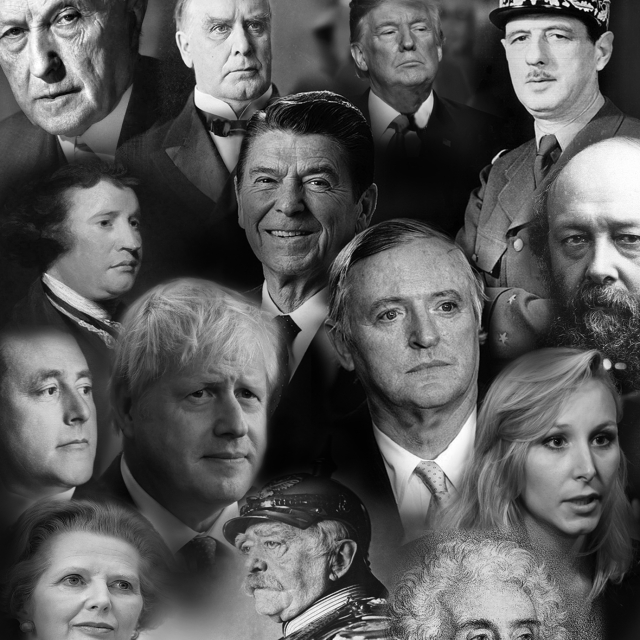

This is a lightly adapted excerpt from Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition by Edmund Fawcett.

About the Author

Edmund Fawcett worked at The Economist for more than three decades, serving as its chief correspondent in Washington, Paris, Berlin, and Brussels, as well as its European and literary editor. His writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Guardian, the New Statesman, and the Times Literary Supplement. He is the author of Liberalism: The Life of an Idea (Princeton).