Joshua Specht puts people at the heart of Red Meat Republic—the big cattle ranchers who helped to drive the nation’s westward expansion, the meatpackers who created a radically new kind of industrialized slaughterhouse, and the stockyard workers who were subjected to the shocking and unsanitary conditions described by Upton Sinclair in his novel The Jungle. So, who are some of the main players in this story? Specht offers a brief primer in these character sketches.

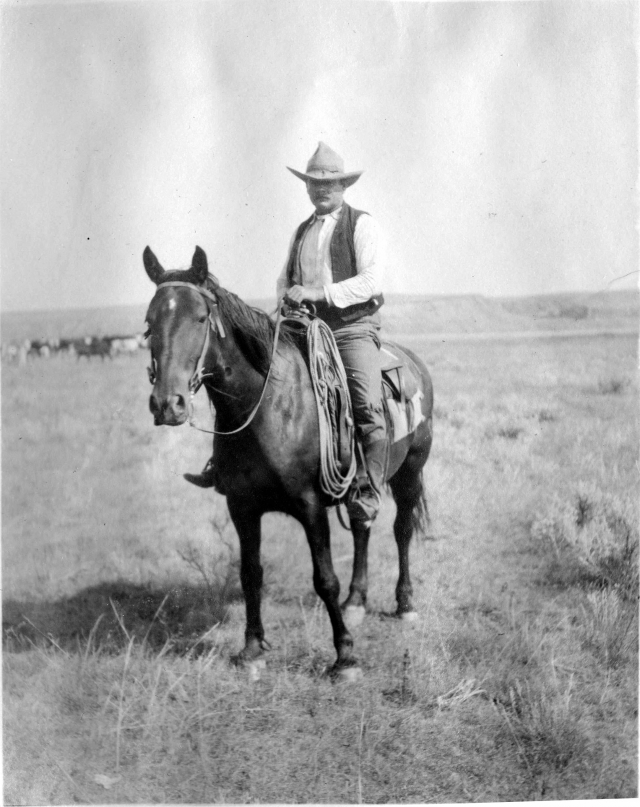

Way Hamlin Updegraff

Way Hamlin Updegraff* was a cowboy by trade, but a comedian by disposition. In a series of letters to his mother back in Elmira, NY, he chronicled his life as a New Mexico cowboy during the 1880s. These letters freely mix the romance of being a cowboy with Updegraff’s often-hilarious analysis of ranch life. In one particularly energetic letter from September 1886, he complains about a new pair of pants which has a fatal error of design: “Mr G. brought my corduroys…after I had gotten [them] on, admired their fine fit, I was naturally a trifle proud, and went to stick my hands in my pockets to strut around a little—but I couldn’t find the pocket and Holy Moses! On minute examination I found I didn’t have any in front. Now, by the greatness of Peter the Great, how in thunder do you suppose a cowboy can get along without pockets?” Updegraff rants a bit more about his pants before concluding “I would have much preferred to have had you send me three or four pairs of good sized pockets than pants in such a condition.” Updegraff’s letters reveal the world of cattle labor during the 1880s, but they also reveal the importance of the cowboy myth, even to the participants themselves. Updegraff recounts his struggles with difficult and often poorly-paid work, but in response to his mother’s anxious pleas for him to return, observes, “the longer I stay the longer I want to stay.”

Walter Baron von Richthofen

Born in Silesia, Walter Baron von Richthofen moved to Denver, Colorado and became a town booster. He wrote Cattle-Raising on the Plains of North America, which argued that almost anyone could get rich on the plains. His guide is extremely detailed, featuring not only inspirational stories—an Irish servant girl turned $150 in back-pay into $25,000 in cattle!—but step-by-step instructions to doubling your money in only five years. Before you go out and buy Richthofen’s guide, however, remember that if someone really has a formula for getting rich quick, they probably aren’t going to waste time writing a book. Nevertheless, Richthofen did seem to be a genuine believer in western development and particularly in the commercial fortunes of Denver. He lived in a kind of latter-day castle that you can still see today in east Denver.

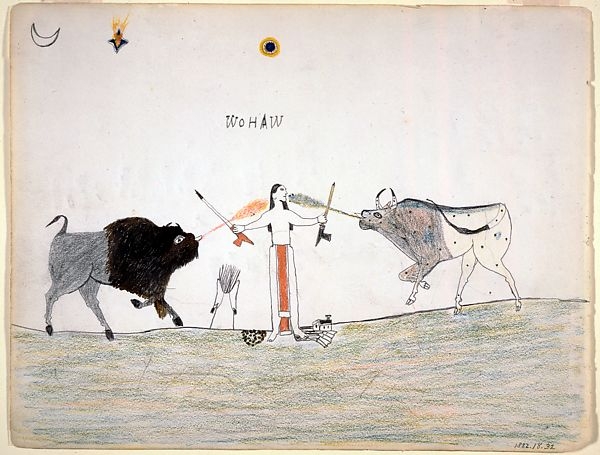

Wo-Haw

Wo-Haw is one of the great artists of the American West. A Kiowa man, he fought first against the encroachments of American settlers and later against the power of the United States. He was captured on the Southern Plains in 1875 and incarcerated in Fort Marion, Florida, where he produced “ledger drawings” chronicling his life. Using colored pencils and notebook paper, these works recreate a traditional style that was painted on animal hides. This was more necessity than artistic innovation; notebook paper was all Wo-Haw had available during his captivity. His 1877 work, “Between Two Worlds,” which opens chapter one, shows the artist torn between the world of cattle and settled agriculture and the world of the bison and its hunt. Wo-Haw uneasily faces the invading creature, pipe extended. Wo-Haw’s art captures a moment of transition for the Southern Plains as well as reflects the violence inflicted on the world of the Kiowa and their Plains Indian allies.

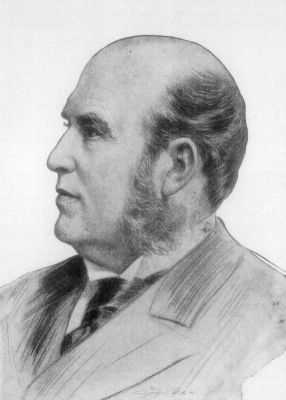

Philip Danforth Armour

Big man, big ego, big personality. Armour was the head of the meatpacking firm Armour & Company. When asked about his fortune, he claimed it had its origins in waste, explaining, “after a while we shall see other fortunes made, like mine has been, out of the things we now waste.” Armour was a shrewd and ruthless businessman with a hatred of organized labor that was as much ideological as practical. During an 1886 meatpacking strike, he not only refused to compromise with striking workers but was alleged to have used his influence over small-meatpackers to ensure they would “dance as he fiddles” when it came to handling their own employees. Creating the cattle-beef complex was about far more than Armour and his meatpacking compatriots—whatever they might have claimed—but Armour and his ilk were certainly its chief beneficiaries.

Joshua Specht teaches American history at Monash University in Australia. He divides his time between Melbourne and South Bend, Indiana. Twitter: @joshspecht