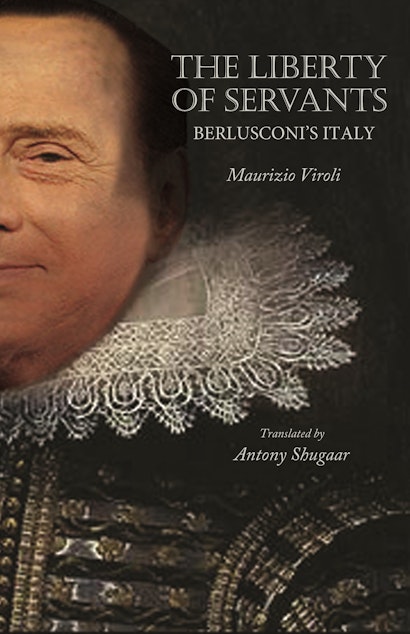

Italy is a country of free political institutions, yet it has become a nation of servile courtesans, with Silvio Berlusconi as their prince. This is the controversial argument that Italian political philosopher and noted Machiavelli biographer Maurizio Viroli puts forward in The Liberty of Servants. Drawing upon the classical republican conception of liberty, Viroli shows that a people can be unfree even though they are not oppressed. This condition of unfreedom arises as a consequence of being subject to the arbitrary or enormous power of men like Berlusconi, who presides over Italy with his control of government and the media, immense wealth, and infamous lack of self-restraint.

Challenging our most cherished notions about liberty, Viroli argues that even if a power like Berlusconi’s has been established in the most legitimate manner and people are not denied their basic rights, the mere existence of such power makes those subject to it unfree. Most Italians, following the lead of their elites, lack the minimal moral qualities of free people, such as respect for the Constitution, the willingness to obey laws, and the readiness to discharge civic duties. As Viroli demonstrates, they exhibit instead the characteristics of servility, including flattery, blind devotion to powerful men, an inclination to lie, obsession with appearances, imitation, buffoonery, acquiescence, and docility. Accompanying these traits is a marked arrogance that is apparent among not only politicians but also ordinary citizens.

Maurizio Viroli is professor of politics at Princeton University and professor of political communication at the University of Italian Switzerland in Lugano. His many books include Niccolò's Smile and Machiavelli's God (Princeton).

"Brave and original. . . . [A] compelling inquiry into intellectual and political history."—Joseph Luzzi, Times Literary Supplement

"This short book is Viroli's diagnosis of what is wrong with Italy and with Italians."—Richard Bosworth, Times Higher Education

"A book that compares the prime minister unfavorably to Machiavelli's Prince."—Stephan Faris, Time Magazine

"Viroli's is a gripping and at times funny, if overall depressing, exposé of how the prime minister and media mogul has hollowed out the country's democracy. Surrounding Berlusconi in parliament and everywhere else, he writes, is a modern-day court populated by thick ranks of flatterers, and, of course, beautiful, busty women who resemble the courtesans of a bygone era."—Erica Alini, Macleans

"[Viroli] holds up Berlusconi's success as a mirror, asking what it tells us about modern democratic societies everywhere. Viroli believes it calls into question the fashionable libertarian conviction that freedom alone is enough to optimize politics, the belief that the state should defend only 'negative liberties,' leaving us alone to enjoy our property, opinions, and rights."—Andrew Moravcsik, Foreign Affairs

"Viroli's thoughts and ideas about what went so wrong in Italy need to be understood and heeded if the country is to succeed in its present struggle and fulfil its potential."—Kate Saffin, LSE Politics and Policy

"Viroli's contribution has the merit of retrieving an important part of the debate over contemporary Italy, namely the role of public morality. At its high points, the book is largely successful in avoiding both the Scylla of simply accusing Italians of a nearly ontological lack of moral standards, and the Charybdis of a blanket absolution in the face of the necessities of living in a profoundly clientelistic and economically increasingly polarized country."—Andrea Teti, Journal of Modern Italian Studies

"In this razor-sharp, beautifully crafted, historically informative, and deeply thoughtful exposé of Berlusconi's degrading 'courtier' regime, one of our foremost intellectual historians and political theorists shows how citizens can voluntarily surrender political liberty for private freedom. For anyone concerned with the dire condition and future prospects of Italy today, Viroli's civic indignation is both an education and an inspiration."—Stephen Holmes, New York University