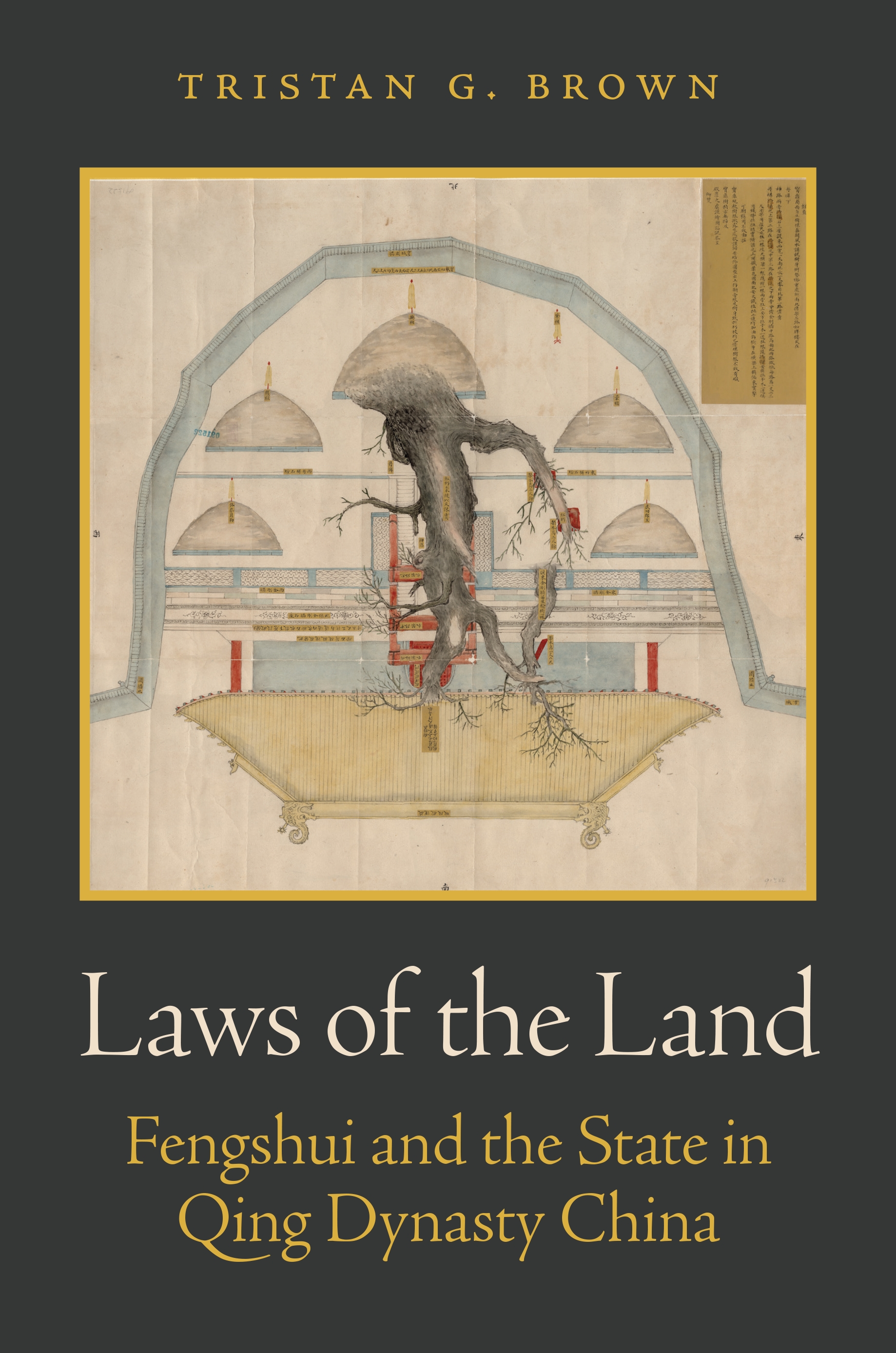

Today the term fengshui, which literally means “wind and water,” is recognized around the world. Yet few know exactly what it means, let alone its fascinating history. In Laws of the Land, Tristan Brown tells the story of the important roles—especially legal ones—played by fengshui in Chinese society during China’s last imperial dynasty, the Manchu Qing (1644–1912).

Employing archives from Mainland China and Taiwan that have only recently become available, this is the first book to document fengshui’s invocations in Chinese law during the Qing dynasty. Facing a growing population, dwindling natural resources, and an overburdened rural government, judicial administrators across China grappled with disputes and petitions about fengshui in their efforts to sustain forestry, farming, mining, and city planning. Laws of the Land offers a radically new interpretation of these legal arrangements: they worked. An intelligent, considered, and sustained engagement with fengshui on the ground helped the imperial state keep the peace and maintain its legitimacy, especially during the increasingly turbulent decades of the nineteenth century. As the century came to an end, contentious debates over industrialization swept across the bureaucracy, with fengshui invoked by officials and scholars opposed to the establishment of railways, telegraphs, and foreign-owned mines.

Demonstrating that the only way to understand those debates and their profound stakes is to grasp fengshui’s longstanding roles in Chinese public life, Laws of the Land rethinks key issues in the history of Chinese law, politics, science, religion, and economics.

Awards and Recognition

- Winner of the John K. Fairbank Prize, American Historical Association

- A Choice Outstanding Academic Title of the Year

Tristan G. Brown is assistant professor of history at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

"Laws of the Land is a gripping, overdue study: enlightening, challenging, and utterly inspiring."—Wendy Xiaoxue Sun, Asian Review of Books

"Brown’s study makes it possible to reconstruct what happened to the Chinese order in the period between the Industrial Revolution, the establishment of the capitalist model of production, and the global development of colonialism. The volume complements and enriches the work of economic historians such as Giovanni Arrighi, Kaoru Sugihara, Bin Wong, and Fernand Braudel."—Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas

"Excellent . . . Meticulous and fascinating."—Choice

"With Laws of the Land, Tristan G. Brown fundamentally reframes the debates over fengshui in the Qing. . . . This is an important provocation to historians of Chinese law, religion, and environment, and it should be widely read by students and scholars in those fields and in modern Chinese history more broadly."—Ian M. Miller, Twentieth-Century China

"[Laws of the Land] is carefully, thoughtfully, and elegantly crafted."—Hailian Chen, H-Water

“Brown offers an impressive, fine-combed reading of sources that paint a vivid picture of fengshui’s signature importance within local life and Qing law. A terrific contribution to Chinese history.”—Jonathan Schlesinger, Indiana University, Bloomington

“A rare look into the intersection of state power and cosmic power in Qing China, Laws of the Land demonstrates how this intersection was intentional and vital to the survival of the empire. Breaking from the Orientalist and imperialist denigrations of fengshui as a superstition, this meticulously researched book argues that the persistence of fengshui resulted from its mutual constitution with Qing law itself.”—He Bian, Princeton University

“Laws of the Land is a significant book. Brown sheds new light on the concrete matters of local economy, environment, and society and some classic issues of Qing history—for example, environmental change and the cultural valuation of nature, the roles of astrology and geomancy in decision making, and the nature of popular resistance to railroads. And the wall between superstition and rationality is dismantled, allowing new insights into China’s transition from the imperial to the republican era, from the ‘traditional’ to the ‘modern.’ ”—Pamela Kyle Crossley, Dartmouth College