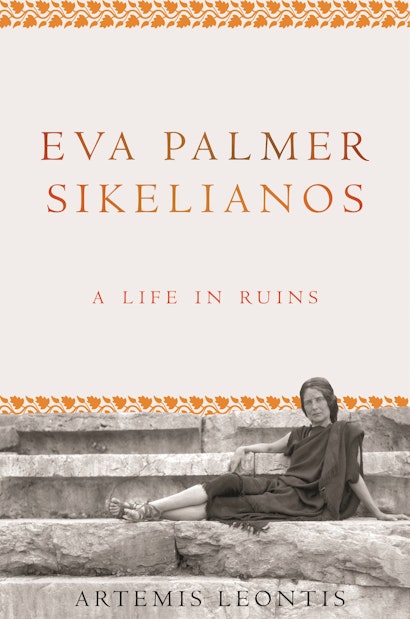

This is the first biography to tell the fascinating story of Eva Palmer Sikelianos (1874–1952), an American actor, director, composer, and weaver best known for reviving the Delphic Festivals. Yet, as Artemis Leontis reveals, Palmer’s most spectacular performance was her daily revival of ancient Greek life. For almost half a century, dressed in handmade Greek tunics and sandals, she sought to make modern life freer and more beautiful through a creative engagement with the ancients. Along the way, she crossed paths with other modern artists such as Natalie Clifford Barney, Renée Vivien, Isadora Duncan, Susan Glaspell, George Cram Cook, Richard Strauss, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Nikos Kazantzakis, George Seferis, Henry Miller, Paul Robeson, and Ted Shawn.

Who is Eva Palmer Sikelianos? Please introduce her to us.

AL: Creative, brilliant, and stunning with floor-length red hair, she was an American actor and director who loved women and ancient Greece and forged an artistic alliance with her Greek poet husband Angelos Sikelianos that shaped twentieth-century Greek culture.

The life of Eva Palmer Sikelianos (1874–1952) reads like a novel. She was born into a wealthy New York family. Her father, Courtlandt Palmer, a freethinker trained at Columbia Law School, was from the Palmers of Stonington, Connecticut and her mother, Catherine, a musician, from the Amory family of Boston. Home-schooled among artistic luminaries and business scions, she boarded at Miss Porter’s School in Farmington, Connecticut after her father’s sudden death in 1888. She studied Greek and Latin at Bryn Mawr College.

Throughout her life, Eva was a non-conformist. She seduced Natalie Clifford Barney in Bar Harbor (by Barney’s recollection) and followed her to Paris in the early 1900s. They aimed to create a woman-centered utopia reviving the spirit of Sappho’s Lesbos. Willful anachronism was part of their artistic practice. Eva, immersed in theatricality and Greek sources, devised the hairstyles, dress, music, gestures, scenery, and props for Barney’s performances that played with gender ambiguity.

She pursued another Greek-inspired utopia in Greece when her tempestuous relationship with Barney became unbearable. Dressed in sandals and a tunic she wove for one of Barney’s plays, she traveled to Greece with Raymond Duncan (brother of dancer Isadora) and his wife Penelope in 1906. She met Penelope’s brother Angelos Sikelianos. They married and settled in Greece the next year, giving birth to a son, Glafkos, in 1909. For 25 years, she promoted endangered musical practices, weaving, and handicrafts as forms of resistance to economic domination by the West. With Sikelianos as the public face of the events, she produced and directed two festivals of drama and games in 1927 and 1930 in the archaeological site of Delphi, spending all her money. The Delphic Festivals—expressions of an international modernist Hellenism grounded in the Greek present— used modern Greek expressive means to signal their Greece’s transhistorical survival. They helped popularize the performance of Greek drama in ancient sites in Greece and across the Mediterranean.

Now deeply in debt, Eva returned to the U.S. in 1933 to raise cash. She directed Greek plays and wove costumes to keep a roof over her head. The struggle to survive broke her health but not her spirit. By the mid-1940s, British and American interference in Greece’s internal affairs had radicalized her politically. She wrote over a thousand letters to politicians and newspaper in protest of American imperialism. The House Un-American Activities Committee listed her name four times on suspicion of campaigning to “disarm and defeat the United States.”

Though denied a visa to return to Greece in 1951, she did eventually return in the spring of 1952 to attend the third Delphic revival, a small festival of drama and part of the “Return to Greece” postwar tourist campaign supported by the American Marshall Plan. There she witnessed her vision for a Greek revival deployed by Greek and American officials to transform Greece into a tourist destination, something she strongly opposed. She suffered a stroke on site and lies buried in the village cemetery of Delphi.

Although best known for reviving the Delphic Festivals, her most spectacular performance was her personal unscripted daily revival of the ancient life. For almost half a century, she performed Greekness in handwoven tunics and sandals in defiance of fashion norms, working to make modern life freer, more authentic, and better.

Why did you write about Eva Palmer Sikelianos? How do you value her achievement today?

AL: She is an overlooked person of the 20th century, airbrushed from depictions of her era’s cultural attainments. I felt that it was time for someone actually to delve into the sources of her life to piece together her story.

Careful digging yielded enormous returns. I read the Greek translation of 163 of Eva’s previously unpublished letters to Barney published in 1995 and discovered over 600 more personal letters in a library in Athens, including 182 exchanged with Barney. Thus, I learned that her connections to Natalie Barney’s turn-of-the-century lesbian salon ran deeper than anyone anticipated. Studying her official archive, I saw that she was also a bigger player in the Delphic Festivals than previously acknowledged; Angelos Sikelianos deliberately covered over her seminal work. There were more, important unexplored episodes. Her search for alternative, tonalities linked her to Richard Strauss, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Konstantinos Psachos, an expert in Byzantine music, and Khorshed Naoroji, the classically trained pianist from Bombay who sought Eva’s help to recover Hindi music. Through Nairoji, her costuming for the Prometheus Bound became interwoven with Gandhi’s advocacy of khadi in India’s decolonization movement. She was also a missing figure in the genealogy of modern dance from Isadora Duncan to Ted Shawn and Martha Graham. Her legacy shaped Greece’s post-War tourist development.

What do we see when we connect these pieces? Her slight, endlessly determined figure, finding its place as a crucial link in a series of artistic and socio-political endeavors, helps clarify the relationships of tesserae in the mosaic of cultural modernism. With her in the picture, modernism’s mantra to “make it new” (Ezra Pound), which placed ultimate value on novelty, becomes “make it ancient”: a determined effort to renew the modern world by capturing the latent energy in ancient sources as creative ground for expression. This was something many modernists actually aspired to.

Moreover, her presence connects the early twentieth-century search for new artistic forms with a queer temporal sensibility in women’s classical learning. Through Eva Palmer’s performances of the Greeks, we see the anachronistic temporality of other modernist projects which moved not progressively forward toward fulfillment, but backward, into the holes of history, to recover a past that never was in order to suggest an as yet unimagined future.

Sometimes a book needs to be written because a person’s strange life suddenly makes sense. I’ve known about Eva Sikelianos for as long as I can remember. For many years, those Greek tunics and the Delphic Festival pressed unproductively against my brain. I did not have the right frame to process them. In the early 2000s, when I read the 163 letters to Barney, in which they imagine new gender and social roles by going back in time, the anachronism of her untimely aspects suddenly made sense.

The idea that new bodily exercises recycling older aspects, performed habitually with self-awareness, may alter the field of possibilities of a restrictive inherited world is quite current. Many people today believe that identities are not innate to individuals but performed through the vocabularies, gestures, and materials recognized by society. This counter-Enlightenment position was tested by a people in the aestheticist movement of Eva Palmer’s youth. Given a new spin in the late twentieth century by Michel Foucault and some of his interpreters, it became ascendant in the twenty-first. Millions of people today work at being themselves by becoming otherwise. They change their names; cross dress to challenge gender binaries; transition to live and present in alignment with another gender identity; tattoo their bodies; draw on ancient traditions and distant sources to transform their consciousness. They aspire, somewhere, somehow, to change the social order through their alteration of the field of possibilities defining themselves.

My hope is that a textured interpretation of the life of Eva Palmer Sikelianos, who, for the first half of the twentieth century, sustained a conscious practice of living differently while absorbing the shocks and heartbreaks of noncomformity, might serve as a meditation on our times.

You mention several artists with whom Eva Palmer Sikelianos’s crossed paths. Who are some of the other famous people in her story?

AL: Her archival materials cover a lot of ground. We find in them the old upper-class families across the world: the Barneys, Beechers, Roosevelts, Vanderbilts, and Andrew Carnegie in the U.S.; Antonis Benakis and Eleftherios Venizelos in Greece; Rabidranath Tagore and the Naorojis in India. This is a sampling.

In the performing arts, I’ve mentioned Barney’s turn-of-the-century lesbian salon. Sara Bernhardt, Colette, Marguerite Moreno, and Isadora and Raymond Duncan are some of the people she worked with that first decade. Mrs. Patrick Campbell offered her acting work on the condition that she cut her ties with Barney, but she wouldn’t. George Cram Cook, Susan Glaspell, photographer Nelly Sougioutzoglou-Seraidare, filmmaker Dimitris Gaziadis, artist Yannis Tsarouchis, Koula Pratsika, an important figure in Greek dance history, and Aliki Diplarakou Lady Russell, who won the Miss Europe contest in 1930, were part of the Delphi scene. In the U.S., Eugene O’Neill supervised her work on the Federal Theater Project. Artist Katherine Dreier introduced her to Ted Shawn. She corresponded with Paul Robeson and W.E.B. DuBois on politics and asked Robeson to play Prometheus in a performance she never staged in Delphi. She was the teacher, friend, and possibly lover of Mary Hambidge, weaver and founder of the Hambidge Center craft community in Georgia, who gave her shelter in the 1930s and 1940s. Greek folklorist Angeliki Hatzimihali was also a dear friend.

She had many connections in the music world. Soprano Emma Calve and harpsichordist Wanda Landowska were possibly her lovers. Natalie Curtis Berlin, a pianist who collected Native American music, was a family friend. She collaborated with Psachos, Greece’s first professor of Byzantine music, and Greek musicologist Simon Karas. Dimitris Mitropoulos stayed in her house near Corinth in 1924 composing music for Angelos’s poetry, and Richard Strauss and his architect Michael Rosenhauer visited her in Delphi two years later while planning to build a music hall on Philopappos Hill in Athens.

Her literary connections begin with Oscar Wilde and continue with Barney, Lucie Delarue-Mardrus, Collette, and Renée Vivien. Playwright Constant Lounsbery and novelist Elsa Barker were longtime friends. In Greece she knew the most prominent writers of the twentieth century: Sikelianos, Kostis Palamas, Nikos Kazantzakis, Kostas Karyotakis, and George Seferis. She corresponded with translators Kimon Frier and Rae Dalven. With Henry Miller she nominated Sikelianos for the Nobel Prize.

She knew all the heads of archaeological schools and many classicists and archaeologists in addition to artists working in the margins of the discipline: Joan Jeffery Vanderopol, Georg von Pscehke, and Alison Frantz. Archaeologist Theodore Leslie Shear was her correspondent on Cold War political matters in the 1940s. Bryn Mawr College presidents, professors, and alumni were her acquaintances, lovers, or good friends, including president M. Carey Thomas, Lucy Donnelly, Virginia Yardley, and Edith Hamilton, popularizer of Greek literature and myths with whom she corresponded about Greek tragedy for over a decade.

So many people, so much material! How did you deal with this embarrassment of riches?

AL: There really is a lot. I visited over 15 archives and libraries in 12 cities in 3 countries on 2 continents.

The archival abundance was especially challenging because much of it was underprocessed. No biographical account existed except the autobiographical episodes in Eva Palmer Sikelianos’s book, Upward Panic. There was not even a reliable timeline of her life to build on. Moreover, access and the organization and contents of archives kept shifting. In one archive, for example, I was given access, then denied it, then given it again to a collection of very personal letters that had been hidden for years. There I found the letters I mentioned earlier. I could not have written a book without those letters. Barney’s own literary executor François Chapon didn’t know they existed. Later I learned that there were 10 more boxes of uncatalogued materials from a later period in Eva’s life.

Every biographer should have such problems!

Besides the challenges of reading and intepreting source materials, selecting was the bigger challenge. There is more material than can possibly fit into a book. To deal with this overabundance, I wrote a detailed chronology to give order to people and events. This is where I map out the historical coordinates of Eva Palmer Sikelianos’s life from birth to death, her burial, and the handling of her remains. I also connect her to many of the people with whom she interacted.

The book I chose to write takes another direction. It brings focus to her life’s work—her body of work and her work shaping her life —as it shifts from one medium to another: from lesbian performances and weaving, patronage of Greek music, staging ancient drama to writing, translating, and political activism in the last phase of her life. I follow the continuities and discontinuities to link Eva Palmer, the stage manager and actor who made Sappho a model of emulation for twentieth-century lesbian identity, with Eva Sikelianos, the director of the Delphic revivals and unconventional dresser who made her life a Greek revival.

Did the source materials present other challenges?

AL: The intimate sources of a person’s life always raise ethical questions in addition to the practical and legal ones of access and permission. On the legal side, who owns the rights and when, where, and how to track that person or entity down. What happens when they are not found? The ethical questions are more layered. We can ask the executors of a deceased person’s work for permission. But what about the wishes of people invested in the person’s legacy? I’m not talking just about people who are now dead. I believe the wishes of anyone living today who has a stake in Eva Palmer Sikelianos’s legacy actually matters. Yet the wishes are many and conflicting.

I struggled long and hard with the question of how to handle the intimate materials. It was not a problem of permission to reveal details of Eva Palmer/Sikelianos’s sexual life. Eleni Sikelianos, Eva’s great grand-daughter and an important American poet, who is her literary executor, wrote in 2005 about her “lesbian theater director great-grandmother.” People heard her grandfather Glafkos express his firm wish that Eva’s sexual orientation should be known and respected. She gave me permission to use every source and to write what I think ought to be said.

Initially, I intended to avoid writing about her intimate relations. I considered them irrelevant to her creative processes. I was trying to get at Eva’s ideas as they expressed themselves publicly in the media of her life and staged performances. As I dug deeper into the sources, I read the many letters exchanged between Eva and Barney and dozens of other women who corresponded intimately with Eva. Some love letters mixed creativity, passion, pain, and despair with deep cultural knowledge about Greek sources and efforts to recreate it. There were letters from Eva’s brother and mother too. Some were especially harsh, belittling her life choices. Her mother wished her to reveal herself yet would not accept her choices.

As I read the archival material, particularly the most personal letters, I sensed just how arbitrary and absurd yet resolutely stigmatizing the social rejection of same-sex orientation has been. At the same time, I observed that Eva’s encounter with the world as a lesbian was inextricably intertwined with her efforts to make herself free and anachronistically ancient. This was true when she cultivated a lesbian life in the company of Barney in the early 1900s and even more true when she “went Greek” after she married Angelos Sikelianos. I chose to disclose those points of intimacy that spoke to the creative process.

So the great loves of her life were…

AL: Natalie Clifford Barney and Greece. Angelos Sikelianos is folded into Greece, and many other women are folded into both great loves. Eva’s correspondence from 1906 to 1907 suggests that she had trouble imagining herself close to Angelos when they first met. She was actually trying to find new footing away from Barney. Yet, in writing Upward Panic thirty years later, Eva made Angelos out to be the love of her life. She grew to love him, I think, but in an expansive way that embraced his dreams and artistic work under the big umbrella of Greece. In her words, she loved “his country, his people, his language, and most of all his dreams.”

She also loved his sister Penelope, and this love is a driving force in my narrative. I guess you will have to read the book to learn how.

You call her “Eva.” How much intimacy do you feel for her?

AL: I use the first name, “Eva,” for a practical reason. Many people in her story share the last names Palmer and Sikelianos. I generally refer to her siblings also by their first names, Robert, May, and Courtlandt, and to Angelos Sikelianos and Penelope Sikelianos Duncan as Angelos and Penelope. The Duncans are Isadora and Raymond, whereas Natalie Clifford Barney is Barney. The reason is not familiarity but to keep my subjects clear, since many people share the last name. Additionally, this spares me the trouble of specifying the maiden, married, or maiden and married, unless there is a point in using these, as in this and the next paragraphs.

As a general principle, I wanted my feelings for Eva Palmer Sikelianos to be irrelevant to the project. This is not to say that I had none or that they did not interfere with the research. I spent many years digging deep into biographical sources. They moved me. There were times when they caught my breath. When I opened the inaccessible dossiers containing over 600 letters for the first time my jaw dropped. Each dossier contained several folders of letters spilling out in loosely bundled stacks, tied with purple, pink, baby blue, and flowered satin ribbons from the time of their receipt. I found traces of tears and mud. The letters absorbed me so utterly that I could do think about anything else. I barely cared about putting dinner on the table. Yet while I was researching and writing, I was also teaching, advising, socializing, and caring for people in my intimate circle. Sometimes I would actually forget “Eva” or be very frustrated that her life always occupied me.

Researching a human subject inspires a certain kind of identification, even attachment, that is different for me at least from other subjects. Eva expressed love, pain, desolation, despair, bias, weakness, doubts, and extreme certainty. I did not always sympathize with her ideas or find her work extraordinary. Since she was a historical subject, I didn’t control her story, as I would have if she were a fictional subject. I compensated by wanting to protect her when things got bad, or to cover for her when she was wrong or just insufferable.

These were some of the feelings I struggled with while writing the book. They may become confused with my using her given name. But my calling her “Eva” is not meant to signal familiarity. I am now as far from knowing “Eva” as I was when I began. But it does solve a practical problem.

What happened in the way you think as a result of writing this biography? Did it change you?

AL: A lot. It changed my thinking about LGBQT culture, as I describe above. This was life changing.

It also changed my attitude to life writing. When I started writing a book about Eva Palmer Sikelianos, a surprising number of colleagues questioned my decision. “You’re not writing a biography,” one person I respect a great deal stated decisively. Several others took time to enumerate why they dislike biographies. Actually, I wasn’t intending to write a biography. Initially, this was going to be a book of essays about Eva Palmer Sikelianos’s work reviving Greek cultural heritage in five media.

But I could not avoid the life-historical research. Classical models offered precedents for personal constructions of dress, behavior, and identity in addition to cultural products. My interest in the former grew. While ideas of Greece take monumental forms in many of their neoclassical manifestations, they are quite liquid in their passage through life. I came to ask: What new shapes do Greek textual and material fragments take when they inhabit people’s daily life? What becomes of both the ancient ruins and the modern person? How did Eva incorporate them in her daily activities? How did they script her life? How did her intense investment in finding the latent life in ruins change over time to become increasingly an art of life?

I now consider the book’s biographical mode to be vital to its contribution. In working to recover the story of a woman whose rich and diverse work in Greece was fitted to the procrustean bed of patriarchal, nationalist, and heteronormative discourses, I honor several decades of biographical writing that studies the gaps in classical scholarship for clues of women invested personally in the study of Greece and other ancient worlds, who had nontraditional careers, lived their eccentric lives mainly in obscurity, and somewhere, somehow, tried to change the social order through their alteration of the field of possibilities defining not just knowledge but themselves.

Why did you feature “ruins” in your title? She was such a creative person!

AL: She was indeed a creative person but also a broken one working in a country associated with ruins on multiple levels. The title plays on the multiple meanings of “ruins”: as an inspiration for creative work, a signifier of financial crisis and decay, and a central feature of Greece—both literal and metaphorical—in modern times.

Eva’s creativity had its source in ruins. She saw the latent grandeur of the Greeks everywhere, and, over the course of half a century, she embraced fragments of the past, giving them new life. This was her attitude before she came to Greece, when she and Barney were imagining an alternative social order for women reconstructed from the gaps in Sappho’s fragments. It became a worldview grounded in materials and practices after she moved to Greece. She saw fragments of the past everywhere: in archaeological sites, museum objects, folk practices, and the modern Greek language. She sought them out and became increasingly involved with them, conversing with people who excavated artifacts for a living or who collected folk survivals, using their discoveries to make new things. Ancient sites and things were a canvas for her creative interventions.

Concurrently, her life trajectory moved from abundance toward ruination. To produce the first Delphic Festival in 1927, she took out loans against the value of two houses. She never recovered the expenses. For the next six years, she experienced the humiliation of avoiding her creditors, whom she could not repay. She left Greece to escape them and also Angelos, who kept asking her for more money. For the next two decades, she depended on the generosity of friends in the U.S. to board her in exchange for her weaving.

With World War II and the Nazi devastation of Greece during the three-year occupation, Eva’s own fall into ruins and Greece’s intersected. From her humble living quarters in the U.U., she read about women and children who were tortured, forests denuded, and villages plundered or totally destroyed. People she loved disappeared. Reading about an economy in ruins and sensing the people’s hardships, she had to rethink the relations between ruins and her advocacy for Greece.

Ruins are a central metaphor for Greece in its modern history, denoting a rift with the past which the present must work endlessly to repair. During the decade when I was researching and writing this book, Greece experienced a huge government debt crisis leading to economic contraction and coinciding with the arrival of hundreds of thousands of asylum seekers and refugees, a true humanitarian crisis. Poverty spread, bringing hunger and illness. Neighborhoods were abandoned and fell into ruins, where homeless people now stay. Today’s Greece evokes the Greece of Eva. Meanwhile, imagery from classical ruins has appeared repeatedly in foreign media representations to symbolize the sorry state of the Greek economy. It works to flatten and ridicule current reality by identifying it with—what else—the rift with the glorious past of Greece.

I think that Eva Palmer Sikelianos: A Life in Ruins tells a good riches to rags story. It should also generate reflections on the representations and functions of ruins today.

Artemis Leontis is professor of modern Greek and chair of the Department of Classical Studies at the University of Michigan. She is the author of Topographies of Hellenism and the coeditor of “What These Ithakas Mean…”: Readings in Cavafy, among other books. She lives in Ann Arbor, Michigan.