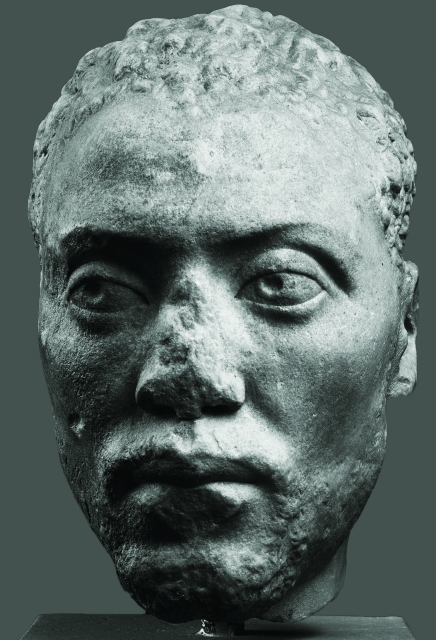

Nat Turner is known to history as a thirty-year-old Virginia slave who led a bloody rebellion that resulted in the death of fifty-five whites, mostly women and children. Beyond that, he is famous for being well-nigh unknowable. He has no gravesite, no remains; there is no likeness of him. To the historian Kenneth Greenberg, Nat Turner is “the most famous, least-known person in American history.”

In the Matter of Nat Turner is an attempt to recover Turner, and his way of thinking. I call it “a speculative history” because it is a work of conjecture, of wondering about the connections between events and causes, between origins and outcomes. To put flesh on the bones of wondering my book inspects the fragments of text in which Turner is materialized and interleaves them with other texts – biblical, theological, philosophical, literary, sociological and anthropological – to tell his story.

Most of what is known of Nat Turner is to be found in a 24 page pamphlet, The Confessions of Nat Turner, written by a Southampton County attorney named Thomas Ruffin Gray who gained access to Turner in jail awaiting trial and over three days heard Turner’s account of himself and his rebellion. Circumstance suggests that much of the pamphlet’s account of the rebellion existed in draft prior to Gray’s conversations with Turner. The first part of Turner’s account, however, dwells on his life from his birth until the rebellion, matters of which Gray could have had little detailed knowledge. It tells of the ascent of a deeply religious personality to a state of grace (“made perfect”) and the consequences attending that outcome.

Turner’s narrative is almost invariably read as Gray designed it, as a single linear account in which the life’s final events appear as an outcome ordained virtually from infancy. But this is a very basic error. Turner describes his painful struggle for spiritual maturity and his search for his calling, both of which become utterly central in his life long before he turns to any clear intimation of interracial violence. The sequence of spiritual experiences, visions and revelations he recounts exhibits a coherent and sophisticated eschatological hermeneutics that moves, as his faith matures, from acceptance of God’s call to discipleship, through visions of the crucifixion and Revelation’s promise of Christ’s second coming, to Turner’s own transfiguration and his assumption of the burden of redemption. His account is of a life of preparation: a precocious infant gifted with uncanny knowledge; an adult tested in the wilderness, come to grace and baptism, confronted in his maturity by an immense task given to him by God that nearly breaks him, on the outcome of which rides the salvation of all. Throughout, Turner employs forms of typological reasoning familiar in evangelical texts for the messianic purpose of re-creating himself as the Redeemer returned.

Notwithstanding this rare opportunity to read the speech of a slave, readers have tended to discount what the slave actually said. The most influential discounter was the late William Styron, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning fictionalized autobiography, The Confessions of Nat Turner (1967), whose repulsion for Turner’s “religious mania” induced him to look for “subtler motives, springing from social and behavioral roots.” Ironically, though he detested the slavery that Gray defended, Styron is just like the Virginia lawyer. Both are modern, rational, and secular. For both, ideas are explained by social circumstance. For both, ideation that social circumstance is unable to explain is insanity.

Historians are not shy of writing about religion, but when they do they usually seek to secularize it. The intellectual orthodoxy of modernity, says Robert Orsi, turns religion into a social construction that “underwrites the hierarchies of power, reinforces group solidarity, and also, if more rarely, functions as a medium of rebellion and resistance.” In the Matter of Nat Turner rejects this orthodoxy.

It is of course tempting to read The Confessions of Nat Turner knowing that at the end of the spiritual odyssey they detail lies a massacre of white slaveholding families undertaken by a group of slaves, to identify that massacre as a “slave rebellion,” and to assume that The Confessions is a narrative of how that slave rebellion came to be. It is nevertheless remarkable that virtually nothing that Turner says during the first part of his confession either embraces, or even hints, that the outcome he planned, or intended, or imagined was a “slave rebellion.” As he says to Gray at the outset, “insurrection” is your word, not mine. So far as Turner was concerned, it was not insurrection that “terminated so fatally to many, both white and black” but “enthusiasm,” which Jordy Rosenberg helpfully defines as “the passionate experience of unmediated communion with God … the capacity of individual subjects to know and understand the divine order.” To discover a slave rebellion in the making in The Confessions we have to accept Gray’s own gloss, read the narrative backwards by privileging the second half’s account of the event itself, and ignore all of Turner’s actual words. We have to treat his apocalyptic eschatology as if it were a secret code referencing something other than itself.

“If one looks upon history as a text,” Walter Benjamin once wrote, “then one can say of it what a recent author has said of literary texts—namely, that the past has left in them images comparable to those registered by a light-sensitive plate. ‘The future alone possesses developers strong enough to reveal the image in all its details.’” The book I have written assembles an array of developers to press upon those fragments of text in which the revenant Nat Turner is materialized, and so reveal their image. It examines as minutely as possible the man, the mind, the events and the circumstances that we associate with the name “Nat Turner.” Its goal is to brush against the grain, to read between the lines, or as Hugo Von Hofmannsthal put it, to read what was never written. “Read what was never written” may seem like an odd injunction for a historian to embrace, but in my view to read what was never written is what the true historian is always required to attempt.

Christopher Tomlins is the Elizabeth Josselyn Boalt Professor of Law at the University of California, Berkeley, and an affiliated research professor at the American Bar Foundation, Chicago. His many books include Freedom Bound: Law, Labor, and Civic Identity in Colonizing English America, 1580–1865 and Law, Labor, and Ideology in the Early American Republic. He lives in Berkeley.