Michael Chwe is an assistant professor in the political science department at UCLA. His recent book, Jane Austen, Game Theorist, has received widespread attention, but it wasn’t by accident. Here he shares his recipe for getting media attention for a book about something interesting, though obscure.

Most people believe that Rosa Parks sparked the Civil Rights Movement by refusing to give up her seat. But as a game theorist who studies social movements, I know this story is only partly true: after Mrs. Parks’s arrest on Dec. 1, 1955, the veteran activist Jo Ann Gibson Robinson mimeographed 52,500 leaflets announcing a boycott four days later. If any single action started the Montgomery Bus Boycott, it was the printing of these leaflets.

Mobilizing people to action doesn’t just happen: it takes extensive planning and effort. So when I geared up to publish my second scholarly book, Jane Austen, Game Theorist, I vowed to deploy ideas from social movement theory to help publicize it. I figured I could use all the help I could get; my first book, Rational Ritual, never cracked an Amazon ranking higher than #42,000. In the heady week after Jane Austen, Game Theorist came out, for a few hours it went past #200. It has received much more attention than anyone expected.

Here’s what I did and why.

When it comes to marketing your book, get ready to spend lots of time and effort, full-time for weeks. It is not unreasonable to schedule your teaching responsibilities around it. You will be spending lots of time and energy doing what all social movement organizers do: talking, writing and discussing, trying to get the message out.

Almost all social movements rely on a single tight organizing team that communicates daily. When you publish your book, your obvious team members are the publicity people at your press and your university. Get to know them early, several months before the publication date, and take their advice.

Planning is essential. A very effective Civil Rights Movement tactic was the sit-in, in which black students sat at segregated lunch counters, causing the lunch counters to shut down and creating economic havoc. In the two months after the Feb. 1, 1960 sit-in in Greensboro, North Carolina, sit-ins had occurred in 69 cities. Many at the time saw this rapid spread as a spontaneous occurrence, like a dam breaking after decades of pent-up frustration, but it was actually the result of extensive planning and nonviolent protest training.

Similarly, the publicists who helped me worked well in advance to get coverage to appear immediately after my publication date. They worked with several outlets at once, and thus news of my book seemed to break spontaneously, giving the impression of a groundswell of support, which turned into a real groundswell of support.

Relationships are key: activate existing ones and make new ones. In the 1964 Freedom Summer campaign, one of the main factors determining whether a given volunteer actually showed up was that person’s personal relationships. The sociologist Doug McAdam found that people who had friends who participated were more likely to participate than people who did not.

You will be surprised at how many people will want to buy your book solely because they know you (from college, kindergarten, conferences, etc.) and want to share in your success. This will gratify you immensely. Get on platforms like Facebook and Twitter and renew these relationships. You have many circles of friends whom you might expect to be uninterested (your gym acquaintances, your PTA friends, your college alumni association) but whom would be delighted to know about your book.

As you promote your book, you initiate new relationships, with interested readers, journalists, bloggers and so on. Take these relationships seriously and make an effort to maintain them. A reporter who wrote about my first book back in 2002 kindly tweeted about my second book to her several thousand followers. Every friend or acquaintance that you have or create has a potential “multiplier effect” of hundreds or thousands. A graduate student who likes your book might not be an “opinion leader” but might tell you about relevant listservs and blogs.

The main stroke of good fortune for my book was that a New York Times reporter, Jennifer Schuessler, wrote a very thoughtful and fun story about it. During my interview with her, I felt that I got to know her a little bit, and I will definitely let her know about my next book.

After the New York Times story came out, I did my best to be active on Twitter, even directing people to bookstores that still had copies, and I “followed” every person who tweeted about the story. Not everyone follows you back, but now I have around 500 followers who have expressed interest in the book, which is great.

Let people know something exciting is happening. In my 2001 book Rational Ritual, I discuss how a political rebellion is what game theorists call a “coordination problem”: a situation in which a person’s motivation for participating increases when other people participate. I am much more likely to join a protest of 10,000 people than a protest of 10. Buying a book is the same: a person is more likely to buy a book if she thinks lots of others are buying it and talking about it.

Thus when you market your book, do anything you can to let potential readers know that there are lots of other potential readers. I set up my own web page for my book, which includes all news stories and blog posts about the book, so people can see how many others are talking about it. If people tweet about your book, retweet. I periodically Google my book title to see which blogs and news outlets might be discussing it, and if possible I leave a comment referring them to my web page.

Make it as easy as possible for people to get interested. In 1965, the economist Mancur Olson recommended that to solve the “free-rider problem,” organizers should offer potential participants “selective incentives.” Any protest organizer who offers free food and music to make a protest more attractive is aware of this logic.

The equivalent of free food for a reporter is anything that makes writing her story easier. Your publicity professionals will create a press release, which is essentially a story pre-written for reporters. Some will post this press release verbatim, and some will modify it slightly and put their name on the byline.

In other words, everyone is busy, so make it easier for people to help you. Try to respond as quickly as possible to inquiries; the time scale of reporters is at least ten times faster than that of academics.

One “selective incentive” that I really like is offering signed bookplates to anyone who wants one for their copy of the book. It is a fun way to get to know your readers, and its personal and analog quality is a welcome respite from the daily digital torrent.

Engage in every way possible. The Civil Rights Movement had its spirituals, and the Gdansk shipyard in 1980 had its poetry. Successful social movements involve people in as many ways as possible, with words, dance, song, poetry, food and so forth. To promote my book, I made a Youtube video because I wanted to engage people with images as well as words.

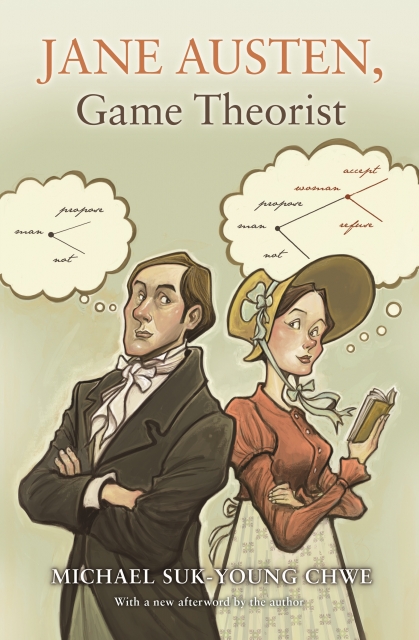

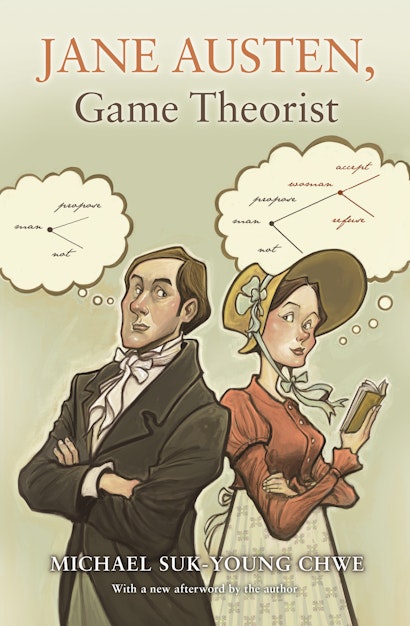

I also got involved with my book’s cover. I wanted the book to feel fun and light, even whimsical, so I emailed the comic artist Sonny Liew and asked him to do the cover. This was money very well spent — Sonny’s fantastic illustration conveys the spirit of my book perfectly. One colleague called it the best academic book cover she has ever seen.

If your book were a meal, what would it taste like? The more ways you can think about the book, the more ways readers can relate to it. I am not above releasing Jane Austen, Game Theorist songs, recipes, and cat pictures.

Finally, start thinking like a 20-year-old. Social movements are usually a young person’s game, with older, more established people carted in after most of the work has been done. According to Alabama State College professor B. J. Simms, 26-year-old Martin Luther King, Jr., having arrived in Montgomery just one year earlier, was elected president of the Montgomery Improvement Association (the organization created to run the bus boycott) because no older leader wanted to take the blame in case it failed.

So to promote your book, do all of the crazy things 20-year-olds do, like Facebook, Twitter, Tumblr, Reddit, Youtube and Imgur. Like a 20-year-old, be willing to drop everything you are doing at a moment’s notice to respond to an inquiry. Be opportunistic, follow every lead and network like hell. Tweet like a maniac — you’ll know you are getting through when people (in this case, Stephanie Hershinow at Rutgers) respond with tweets like “WE GET IT! JANE AUSTEN WAS A GAME THEORIST! FINE! WHATEVER! YOU WIN!!!!”

This article was originally published on UCLA Today’s website.

About Jane Austen, Game Theorist

Game theory—the study of how people make choices while interacting with others—is one of the most popular technical approaches in social science today. But as Michael Chwe reveals in his insightful new book, Jane Austen explored game theory’s core ideas in her six novels roughly two hundred years ago. Jane Austen, Game Theorist shows how this beloved writer theorized choice and preferences, prized strategic thinking, argued that jointly strategizing with a partner is the surest foundation for intimacy, and analyzed why superiors are often strategically clueless about inferiors. With a diverse range of literature and folktales, this book illustrates the wide relevance of game theory and how, fundamentally, we are all strategic thinkers. Although game theory’s mathematical development began in the Cold War 1950s, Chwe finds that game theory has earlier subversive historical roots in Austen’s novels and in “folk game theory” traditions, including African American folktales. Chwe makes the case that these literary forebears are game theory’s true scientific predecessors. He considers how Austen in particular analyzed “cluelessness”—the conspicuous absence of strategic thinking—and how her sharp observations apply to a variety of situations, including U.S. military blunders in Iraq and Vietnam. Jane Austen, Game Theorist brings together the study of literature and social science in an original and surprising way.

Praise for Jane Austen, Game Theorist

“Jane Austen, Game Theorist … is more than the larky scholarly equivalent of ‘Pride and Prejudice and Zombies.’… Mr. Chwe argues that Austen isn’t merely fodder for game-theoretical analysis, but an unacknowledged founder of the discipline itself: a kind of Empire-waisted version of the mathematician and cold war thinker John von Neumann, ruthlessly breaking down the stratagems of 18th-century social warfare.”–Jennifer Schuessler, New York Times

“This is such a fabulous book—carefully written, thoughtful and insightful.”–Guardian.co.uk’s Grrl Scientist blog

“Michael Chwe shows that Jane Austen is a strategic analyst—a game theorist whose characters exercise strategic thinking. Game theorists usually study war, business, crime and punishment, diplomacy, politics, and one-upmanship. Jane Austen studies social advancement, romantic relationships, and even gamesmanship. Game theorists will enjoy this venture into unfamiliar territory, while Jane Austen fans will enjoy being illuminated about their favorite author’s strategic acumen—and learn a little game theory besides.”–Thomas C. Schelling, Nobel Laureate in Economics

“Jane Austen’s novels provide wonderful examples of strategic thinking in the lives of ordinary people. In Jane Austen, Game Theorist, Michael Chwe brilliantly brings out these strategies, and Austen’s intuitive game-theoretic analysis of these situations and actions. This book will transform the way you read literature.”–Avinash Dixit, coauthor of The Art of Strategy: A Game Theorist’s Guide to Success in Business and Life

“Whether you’re an intelligent strategic thinker or a clueless bureaucrat, this book will teach and delight you. The merger of game theory and Jane Austen, with extended examples from African American folklore and U.S. foreign policy, provides the best study I know of motive and cluelessness. Michael Chwe, a rare breed of political scientist, has raised the game of two disciplines. This is a genuinely interdisciplinary work that avoids the reductionism of much game theory and the provincialism of many Austen admirers.”–Regenia Gagnier, author of The Insatiability of Human Wants: Economics and Aesthetics in Market Society

“It would be useful for everyone to understand a little bit more about strategic thinking. Jane Austen seems not only to get this, but to explore it obsessively. Looking at Austen and other works, this persuasive book shows that the game theory in historical sources is not inherently opposed to humanistic thinking, but embedded within it.”–Laura J. Rosenthal, University of Maryland