Bugs are typically considered one of the more annoying aspects of the outdoors. We asked Sara Lewis and Jeffrey Skevington how they would encourage people to reframe their opinions on insects.

Sara Lewis, author of Silent Sparks: The Wondrous World of Fireflies

As an ecologist, I certainly believe that insects deserve more respect! When insects first evolved about 480 million years ago, they were among the first life forms to struggle from sea onto land. And since their arrival, they have enjoyed remarkable success. Blossoming into seemingly endless forms, an estimated 5.5 million insect species now live somewhere on Earth.

Surely some of insects’ evolutionary success relies on the transformational power of metamorphosis. We humans are born as miniature adults – we grow larger, but retain the same body parts. In contrast, insects have the remarkable ability to completely reinvent their bodies as they grow. Virtuosos of change, juvenile and adult insects can pursue independent lifestyles. Juvenile insects mainly specialize in eating and growing, while adults concentrate on mate-finding and reproduction.

If you’re not still inclined to appreciate insects, then let’s consider the firefly. Surely among the most charismatic creatures that share our planet, these iconic insects create magical summer nights with their graceful, luminous dances. Even people who fear insects still love fireflies!

So perhaps it comes as some surprise that fireflies too rise up from humble beginnings. North American fireflies spend most of their lives – up to two years – as grub-like juveniles that live underground. These larval fireflies turn out to be fearsome predators, indulging themselves in gluttony and growth. In one chapter of Silent Sparks, called Lifestyles of the Stars, I follow a firefly through this curious magic of metamorphosis from a tiny egg, to a carnivorous larva that hunts its prey underground, to its final transformation into a mystical, resplendent adult.

But despite their evolutionary success, things are looking bleak for insects. Over the past few decades, researchers all over the world have noted steep declines in insect diversity and biomass. This so-called insect apocalypse has generated widespread public concern, since insects perform valuable pollination services and forge vital links in all terrestrial and aquatic food webs. Alarmingly, there’s compelling evidence that fireflies are also declining. As described in Silent Sparks, the major drivers of these firefly declines are loss of suitable habitat, increased light pollution and overuse of pesticides.

What constitutes suitable firefly habitat? Fireflies prefer undisturbed grassy areas, forests, marshes, and wetlands. While various species (about 170 occur in the US) have different requirements, all fireflies need moisture. During their larval stage, these insects spend 1-2 years living in leaf litter or underground, feasting on earthworms, slugs, and snails. Suitable habitat for these terrestrial larvae will be undisturbed areas with consistently moist soil and abundant prey.

By conservative estimates, light pollution now impacts nearly one-fourth of Earth’s total land surface area. This creates a problem for fireflies that rely on bioluminescent courtship signals to find mates. Excessive artificial light – for instance from streetlamps, outdoor security lights, and electronic billboards – can obscure these courtship signals and make it difficult for fireflies to locate mates.

Pesticides represent another serious threat for fireflies as well as for other insects. Broad spectrum insecticides commonly used in home and agricultural settings like neonicotinoids and pyrethroids are known to kill many non-target insects. Fireflies get exposed to these products via aerial spraying, contact with contaminated soil or water, or ingestion of pesticide-containing prey.

Silent Sparks includes many suggestions about ways you can make your yard more firefly-friendly. Check it out, and remember to #getoutside this summer and enjoy some firefly magic!

Sara Lewis, who has been captivated by fireflies for nearly three decades, is a professor in the Department of Biology at Tufts University. She is the author of Silent Sparks.

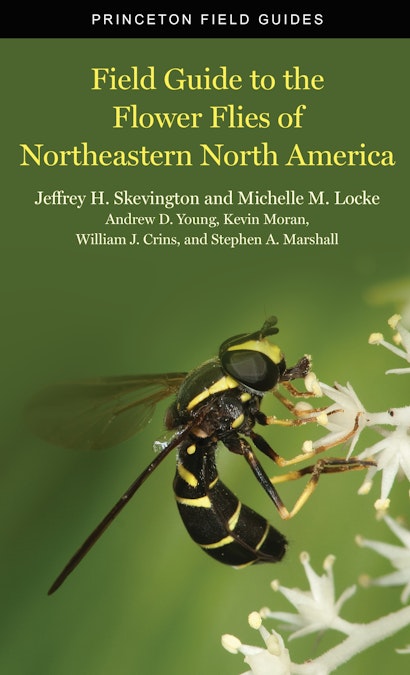

Jeffrey Skevington, co-author of Field Guide to the Flower Flies of Northeastern North America

We live in a world dominated by insects. Sometimes it may seem to us that all of them are pests, but in reality, pest species are an infinitesimally small component of our biodiversity. Just within the world of flies (my research area) there are over 162,000 described species! Despite this daunting diversity, most of our flies remain undescribed and we are confident that over a million species exist! Of these, most go about their business with us being blissfully unaware of their existence. They are the cornerstone of our ecosystem with thousands of species that are decomposers and recyclers, thousands that are parasitoids of other insects that keep numbers in check, and of course thousands that are pollinators. One of my research groups is the flower flies (Syrphidae). We recently published a field guide to this family of spectacular insects. With a little bit of effort, you will find most of them as easy to learn as birds. Most are fabulous mimics of bees and wasps and despite being harmless, are afforded protection by looking like their stinging models. Take a close look at flowers in your garden and you will see that many of the bees and wasps only have two wings. These are likely flower flies (wasps and bees have four wings). Thirty-eight percent of our agricultural pollination is done by non-bees and flower flies are the heavy lifters amongst this group. In natural ecosystems, flies are even more significant pollinators. Once you have figured out what you are looking at, the name will unlock all kinds of additional information about these fabulous little animals. With the name, you will also discover what we don’t know about them. Studying insects is very different from studying vertebrates like birds or mammals. There are still significant gaps in our knowledge that anyone with a bit of passion and a camera can unlock. For example, we have only a partial knowledge of flower species that our flower flies visit and many species still have undiscovered larvae and unknown larval ecologies. There are great online databases such as iNaturalist that you can use to record your observations and contribute to our understanding of these groups. In order to attract more flower flies and other interesting insects to your garden you should focus on planting native species of plants and also try to think about what the larvae may need in addition to the flowers that the adults may use.

Of course, while you are out enjoying the many positive aspects that insects offer, you will likely run across some of the annoying species. If you focus on native species for your gardens, you will have very few problems with pests but of course there will still likely be biting flies around to harass you. A bit of knowledge can help to deal with them. Mosquitoes (Culicidae), black flies (Simuliidae) and no-see-ums (Ceratopogonidae) all use moisture, carbon dioxide and heat from our bodies to find us. Insect repellents containing DEET are effective at confusing their sensors and prevent most from landing on us and biting. Knowing a bit more about their biology also helps. For example, no-see-ums are most prevalent in sandy areas and are most annoying when the humidity is high (just before a summer rainstorm for example). Black flies live near running water where their larvae filter feed in riffles and rapids. All of these flies desiccate if it is hot and dry, so you are unlikely to have problems during the heat of the day. Deer flies and horse flies (Tabanidae) are the most annoying biters because they are visual hunters and DEET has no effect. Your best course of action with them is to remain still or walk beside someone taller than you (most flies will go to them). Sticky traps for your hat work well to capture them but will also stick to your hair if it is long. Stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans) are the only other annoying biting species in our area. This species lives in rotting vegetation along shorelines or around farms. They can be a real annoyance when you are on the beach but rarely bite much above the ankles. Wearing some fashionable socks with your bathing suit should prevent most bites.

Biting flies are kind of like winter for those of us who live in cold parts of the world. Annoying but worth trying to ignore. In that way, we can get outside and focus on the myriad spectacular and interesting insects that make up our environment.

Jeff Skevington is Head of Diptera, Canadian National Collection of Insects, Arachnids and Nematodes. He is coauthor with Michelle M. Locke of The Flower Flies of Northeastern North America.