In 1947, Stalin decreed that eight monumental buildings be built in the Soviet capital. Seven of these neoclassical structures were completed in the 1950s and these buildings continue to stand today as originally intended: as elite apartment complexes, luxury hotels, and the headquarters of key institutions including Moscow State University and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In Moscow Monumental: Soviet Skyscrapers and Urban Life in Stalin’s Capital, Katherine Zubovich explores the history of the monumental structures that transformed the Soviet capital in the years after 1945 and that continue to define the Moscow cityscape today.

What led you to write this book?

KZ: Stalin’s “vysotki”—the skyscrapers that are at the center of Moscow Monumental—are absolutely iconic structures in Moscow. They were built in the last years of the Stalin era, but even today these towers stand out on the horizon. They have an almost magnetic quality, drawing you into their orbit, whether you like it or not. I wanted to know more about the history of these buildings. So, I went to the archives and found that these eight skyscrapers left behind a mountain of paperwork. Reading file after file of documents was like opening up a door to the past. Moscow in the years after 1945 was a city of over 4 million people and it was the capital of a country just recovering from a devastating war. Moscow’s Stalinist skyscrapers were intended to stand as monuments to Soviet victory in the Great Patriotic War, but they were also understood in their time as evidence of the USSR’s emergence as a global superpower. An enormous amount of energy and resources was diverted to the project of making Moscow monumental and I quickly realized that these eight skyscrapers offered a rare vantage point from which to scrutinize the pivotal years of late Stalinism.

You explore the history of these eight buildings, but you also focus on the urban history of Moscow more broadly. What led you to widen your focus in this way?

KZ: Moscow Monumental is a history of Stalinist architectural monumentalism and its consequences. I look at the design and construction of Stalin’s skyscrapers, but also at the unanticipated effects these buildings had on Moscow as a whole and on the city’s inhabitants. The decision to broaden my focus in this way was dictated by the archives. What became apparent immediately in my research was how expansive Moscow’s skyscraper project was. These were huge construction sites spread throughout the city and each one required coordination across dozens of Soviet ministries and between architects, bureaucrats, construction managers, and factories producing materials, just to name a few of the many players.

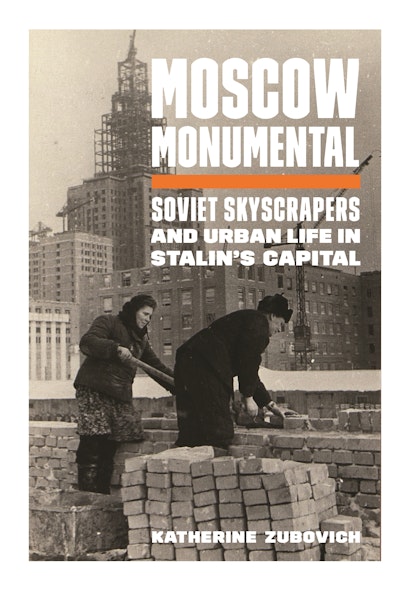

Another important group involved in this process was, of course, construction workers. At a moment that saw the Soviet Union facing a dire shortage of labor, officials opted to bring thousands of workers into Moscow to help build the city’s skyscrapers. These newcomers to the capital included Gulag laborers, who lived in secured zones located near construction sites. In one case, Gulag workers were housed on the unfinished twenty-third floor of Moscow State University. They lived there while completing construction on the upper floors of this skyscraper.

When it was initiated in 1947, Stalin’s city-wide skyscraper construction project was envisioned as a plan that would impose a sense of order onto Moscow’s untidy urban fabric. Stalinist architects hoped that their structures would transform an 800-year-old cityscape into a modern, unified, hierarchical ensemble. But instead, as I show in my book, these skyscrapers had a destabilizing effect on the Soviet capital, adding instability and chaos to the lives of everyone, from state officials to construction workers to ordinary Muscovites.

Can you give an example of how Moscow’s Stalinist skyscrapers impacted the lives of ordinary people?

KZ: Residents of Moscow in the postwar years were affected by Stalin’s skyscrapers in a variety of ways. A group that I focus on in the book is the tens of thousands of Muscovites who were displaced by skyscraper construction. This aspect of Moscow’s postwar vertical development can be compared to the impact of urban renewal projects on Americans in those same postwar years. The eight locations that were chosen for skyscraper development in Moscow in 1947 were occupied by preexisting housing and other structures that would need to be cleared to make way for the city’s new showpiece towers.

Soviet citizens could not freely form community groups or residents’ associations to oppose or prevent urban redevelopment in the way that Americans did in the postwar years. But Soviet citizens could write letters of complaint to officials, who welcomed this practice. Drawing on residents’ letters, which can be found today in the Russian archives, I examine the concerns and objections of ordinary people who found their lives uprooted by Moscow’s skyscraper project. Many of these people objected, in particular, to being moved from their former homes in the center of Moscow to new locations on the city’s outskirts.

Of course, other residents of Moscow benefited from skyscraper construction in their city. Hundreds of late-Stalinist elites moved with their families into apartments in the city’s three new residential towers. In this way, Moscow’s skyscrapers made the social hierarchies of late Stalinism visible on the skyline—those closest to power literally ascended into new high-rise apartments.

Moscow’s Stalinist skyscrapers were built in the first years of the Cold War. How were these structures connected to the emerging geo-political rivalry between the US and the USSR?

KZ: Ironically, it was US-Soviet cooperation that made Moscow’s Stalinist skyscrapers possible. But when the buildings were first construction, American connections were vehemently denied.

The early chapters of my book tell the history of the Palace of Soviets—a tower that, had it been completed in the 1930s, would have been in its time the tallest building in the world. In order to build the Palace of Soviets, Soviet architects and engineers of the 1930s traveled to the United States to learn high-rise construction techniques. The Palace of Soviets was never completed. But the organization created in the 1930s to build the Palace was reassigned in 1947 to construct two of Moscow’s postwar skyscrapers. The expertise that the Palace of Soviets design teams brought to the postwar project was integral to the realization of Stalin’s postwar skyscrapers.

This history of American-Soviet cooperation was not openly discussed in the late 1940s and 1950s. Cold War competition dictated that Soviet officials and architects working on Moscow’s postwar towers would not even refer to their buildings as “skyscrapers” (“neboskreby” in Russian). In Soviet officialese, Moscow’s new towers were labelled “tall” or “multi-story buildings.” American and Western European observers were, similarly, happy to classify the Soviet skyscraper as something “other.” But with the Cold War now firmly behind us, one of my aims in the book is to uncover the transnational ties that supported Moscow’s postwar redevelopment and to reconnect this city’s Stalinist skyscrapers to their international history.

Katherine Zubovich is assistant professor of history at the University at Buffalo, State University of New York. Twitter @kzubovich