The darkest times often feel unprecedented, but as almost any historian will tell you, they’re not. Sure, there are sometimes disjunctive, mind-bending trends: climate weirding and pandemic lockdowns and such. But none of our present-day apocalyptic phenomena are without antecedents. Historians track both change and continuity, and they find that the past is often interwoven with the present—which means that in dark times, history can offer a measure of reassurance.

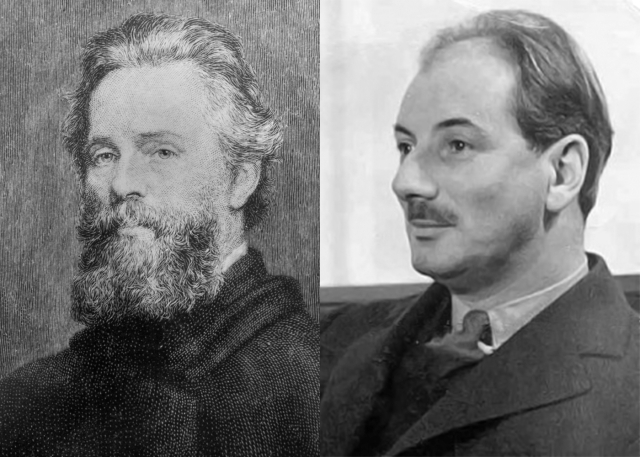

Lewis Mumford was one of the most reassuring historians of the 20th century, as well as one of America’s most influential public intellectuals. He probably helped determine your opinions on modern architecture, cities, and technology. He also lived through, and commented on, World War I, the Great Depression, World War II, McCarthyism, and Vietnam. Given that litany of catastrophes, it might come as a surprise that Mumford remained relentlessly hopeful. He insisted on reckoning with the long record of human disasters precisely because he believed that such reckoning could activate the human capacity for reinvention. “Not once,” he wrote in 1944, as the second World War was raging, “but repeatedly in man’s history, has an all-enveloping crisis provided the condition essential to a renewal of the personality and the community. In the darkness of the present day, that memory is also a promise.”

Remarkably, Mumford anchored his faith in the writings of Herman Melville, whose career and works have so often been understood as tragic. To Mumford, Melville represented determination and perseverance—the will to create meaning in the face of personal and societal chaos. Again and again, throughout his life, Mumford turned to Melville for doses of realistic hopefulness. In a book called Faith for Living, drafted in a 10-day frenzy after the Nazis’ occupation of Paris, Mumford even upheld Moby Dick as a testament to humanity’s staying power: “Melville was optimist enough to provide a ‘happy ending,’ namely someone left to tell the tale.” One resilient survivor, Mumford thought, could be enough to revive a civilization, to keep the story going.

Melville, of course, had to be rediscovered in the 20th century: he had been utterly forgotten in American culture by the time of his death in 1891, despite having achieved wide renown a few decades earlier. A couple of obscure scholars launched what became known as the Melville Revival in 1919, the year Melville would have turned 100. It was a dark time in the United States, as Mumford noted: 1919, he thought, was “the year when the Age of Confidence visibly collapsed.” It was a year of mail bombs, constant labor strife, weekly lynchings, and race riots in 26 cities. Americans seemed to need a forebear with a suitably dark vision. Melville’s first biographer, Raymond Weaver, emphasized his subject’s sense of life’s meaninglessness: “the world to him was a darkly figured hieroglyph.”

Mumford wrote the second biography of Melville in order to offer what he thought of as a more constructive interpretive framework. Yes, Melville may have been despondent at times. Yes, he captured better than almost any other writer the bitterness and perversity of the human condition, and of modernity, skewering his fellow citizens’ blind belief in steady Progress. But what truly matters about Melville, Mumford asserted, is that he never stopped struggling to make meaning of the never-ending struggle. Mumford proposed that in fact Melville had “conquered the white whale in his own consciousness: instead of blankness there was significance, instead of aimless energy there was purpose, and instead of random living there was Life. The universe is inscrutable, unfathomable, malicious, so—like the white whale and his element. Art in the broad sense of all humanizing effort is man’s answer to this condition: for it is the means by which he circumvents or postpones his doom, and bravely meets his tragic destiny. Not tame and gentle bliss, but disaster, heroically encountered, is man’s true happy ending.”

Melville confronted slavery, racism, the Civil War, industrial capitalism, bureaucratization, and Manifest Destiny. In turn, his writings helped Mumford confront the cultural shell shock of World War I, and the mechanization of everyday life, and the spread of environmental degradation, and the terror of the atomic age. Change comes so fast in the modern world that in can be easy to feel completely cut off from the wisdom of the past. But there is a kind of solace in listening for history’s uncanny echoes.

Today, it’s time for a Mumford Revival. Many people are experiencing the present moment as a new dark age, full of foreboding over disease outbreaks, climate change, economic inequality, racial and religious bigotry, technological overload, refugee crises, neo-fascism, and near-constant warfare. Mumford analyzed these kinds of trends with an admirable frankness, always hoping to redirect modern energies toward more humane formulations that might counter some of the violence and trauma. His four-volume magnum opus, published between 1934 and 1951, was called The Renewal of Life. It acknowledged the acceleration of change and the increasing destructive power of the modern era. Then it offered age-old suggestions for how to offset those forces: plant community gardens and labor with the land; uphold justice; make time for the arts; embrace diversity and debate; prioritize schools and museums and playgrounds; practice mutual aid; engage with the past.

The rediscovery of historical continuity is especially precious in a culture that fetishizes Progress and innovation and an orientation toward the future. Modernity feels traumatic to many people precisely because one of the hallmarks of trauma is a sense of temporal rupture: you face a horror, and from now on everything will be different. Those who study trauma suggest that it’s counterproductive to imagine a full recovery: you can never be the person you were before. Rather, the goal is to dwell with the horror as calmly as possible. But the process of working through your trauma may well involve rediscovering older parts of yourself, which, after all, are never completely erased. That holds for societies as well as for individuals. In dark times, the moral guidance of our ancestors reminds us of our obligation to endure.

Aaron Sachs is professor of history and American studies at Cornell University. He is the author of The Humboldt Current: Nineteenth-Century Exploration and the Roots of American Environmentalism and Arcadian America: The Death and Life of an Environmental Tradition.