‘It’s a dangerous business, Frodo, going out of your door.’ Bilbo Baggins is thinking of adventure, of course, not pandemics. ‘You step into the Road, and if you don’t keep your feet, there is no knowing where you might be swept off to.’ Yet The Lord of the Rings is a lesson in how far you can travel without leaving home. Together with the rest of Tolkien’s works, it puts a whole world in your hands. And the great yarn was largely produced by Tolkien at his desk in Oxford in years when World War II curtailed most travel.

No one, however, can spin fabric from thin air, least of all anything with the weft and warp of reality—which Middle-earth has by the yard. Its landscapes are a large part of its power. You feel you are on that road with Frodo, passing through places that existed before you get there.

Part of the reason, I’m now sure, is that in many cases Tolkien had been there himself.

‘My heart is in my works, not on my sleeve,’ he once told an inquisitive interviewer; and he largely kept his inspirations to himself. But as my research shows in The Worlds of J.R.R. Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth, when describing the adventures of hobbits and heroes, Tolkien often drew from his own personal journeys.

Privately Tolkien could be frank about this. A 1947 letter to a fan recalls ‘the summer when I walked over the Misty Mountains long ago (1911)’. He was referring to the Swiss Alps. An unpublished account by one of the walking party helps us map out the route—several weeks roughing it on foot from the Bernese Oberland to the Valais. Walking in a party of a dozen or so led by a feisty aunt, he was nineteen and had just left high school.

‘My heart still lingers among the high stony wastes,’ he said in the midst of writing The Lord of the Rings. It was a truly formative experience, to which his every fictional mountain journey was surely indebted.

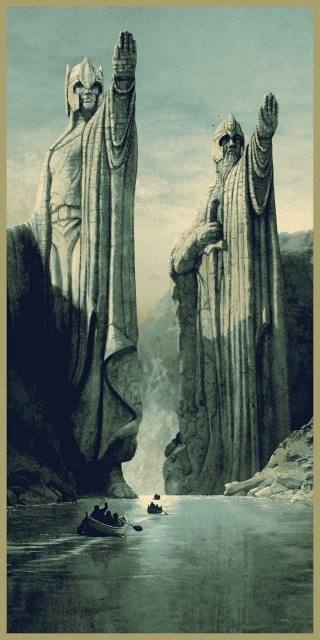

Tolkien recaptured Lauterbrunnen, a precipitous Alpine valley, in drawings and paintings of elven Rivendell, and echoed its name in the English and Elvish names of Rivendell’s river: Loudwater and Bruinen. The nearby Silberhorn was ‘the Silvertine (Celebdil) of my dreams’, he said, referring to one of the three Misty Mountain peaks above the dwarven Mines of Moria.

Still further afield, in Rohan’s White Mountains, the high refuge of Dunharrow seems to have been another reshaping of Lauterbrunnen. This has no Tolkien statement of origin, yet the descriptions fit and rank among the most vivid in the whole vast epic.

Some caveats, though. It would be wrong to think Tolkien was simply writing fantasy as a one-to-one code for reality. That’s allegory, which he largely avoided; and it’s alien to his prodigious creative spirit, which tended towards synthesis and transformation.

Often it’s possible to see multiple sources intertwining in a single fictional scene. When Gandalf battles the demonic Balrog on the peak of Celebdil, it surely harks back not to the Alps but to an overlooked American classic, The Song of Hiawatha, where the hero battles Mudjekeewis on a high peak in the Rockies. It goes without saying that he drew from his reading and scholarship, but place was significant there too. I’ve previously found evidence of other Hiawatha influences; now I’ve found Tolkien’s statement that he read Longfellow’s poem while researching word histories for the Oxford English Dictionary early in his career.

I explore Tolkien’s American interests in a chapter devoted to cultural influence from north, west, south and east. I’m especially struck by his interest in Vinland—but not the archaeologically verified Norse settlements that still get labelled as Vinland. Tolkien cherished the 1911 book In Northern Mists, in which Norwegian explorer Fridtjof Nansen—while not disputing that the Norsemen reached America—argues that Vinland itself was a fantasy, a new manifestation of a much older tradition of Fortunate Lands with self-sowing wheat and vines. This, I believe, helped shape Tolkien’s abiding idea of the Undying Lands of gods and elves across the western ocean, the ‘far green country’ to which Frodo finally voyages.

Inevitably, any exploration of Tolkien’s imagination has to return to Britain, to England. Before it was anything else, Middle-earth was an attempt to restore to England the mythology it had forgotten. Tolkien’s love for his homeland came from the fact that it was not his original home: he’d been born in the torrid veldt of southern Africa. England was the far green country he reached at the age of three. Here his imagination first took flight in stories told to his little brother, in which local farmers appear as ogres.

In the ‘Book of Lost Tales’, written during World War I, Tolkien was quite deliberate about mapping the fictional world onto the real one. He wrote himself and his fiancée Edith into it using various avatars, and imagined that her home town, Warwick, had once been Kortirion, capital of an elven ‘Lonely Isle’. The Lonely Isle would survive into the mature mythology, though there it is the hobbits’ Shire that we most clearly associate with England.

But I believe a little of Warwick found its way even into the elven forest of Lothlórien. At the mound of Cerin Amroth, mortal Aragorn plights his troth to the elfmaiden Arwen. Here Tolkien revived an idea from the Lost Tales, in which the mound of the elf-queen of Kortirion was modelled, it seems certain, on Ethelfleda’s Mound at Warwick Castle.

These deeply personal links between fact and fiction accord closely with Tolkien’s opposition to industrialism and environmental destruction—which I explore in a further chapter focusing on Birmingham, the city of his youth.

Looking carefully into the relationship between fact and fiction, we can see more clearly than ever how much Tolkien’s heart was in his works. In the creation myth at the start of The Silmarillion, the world is created through a heavenly music. Tolkien’s mythology is a love song to the world he knew.

John Garth is the author of the award-winning Tolkien and the Great War (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt). A writer, editor, and consultant, he gives talks and teaches courses internationally. He is also a regular contributor to the Guardian, Daily Telegraph, and other leading publications. He lives in Hampshire, England. Twitter @JohnGarthWriter