On December 12, 2017, the state of Alabama held a special general election for the U.S. Senate seat vacated by Attorney General Jeff Sessions. The race, which had Republican Roy Moore running against Democrat Doug Jones, had already captured national attention. It was supposed to be an easy seat for the GOP to retain—a long-held seat in a deeply conservative state. Then, in November, the Washington Post published the story of a woman who claimed Moore had initiated a sexual encounter with her when she was a young teen and he was thirty-two (McCrummen, Reinhard, and Crites 2017). As more allegations of pedophilia and sexual assault against Moore surfaced, some Republican leaders endeavored to convince the candidate to remove himself from the ballot. He would not. With a Senate seat on the line, President Donald Trump came through with a public endorsement of Moore. And despite the controversy, the likelihood of Moore winning the race in the Republican stronghold remained common knowledge. Trump, after all, had taken the state by a 28-point advantage in 2016. Republican Mitt Romney had carried it by 22 points in his 2012 bid (New York Times 2017).

But Moore lost.

The crucial politics that delivered Jones’s historic upset of Moore, it turns out, were the politics of Alabama’s black citizens. NPR reported on the exceptional nature of black support for Jones: “Black voters made up 29 percent of the electorate in Alabama’s special Senate election, according to exit polling. That percentage is slightly more than the percentage of Black voters in the state who turned out for Barack Obama in 2012. And a full 96 percent of Black voters in Alabama Tuesday supported Jones, including 98 percent of African-American women” (Naylor 2017). The essential role of black voters in the Jones win was undeniable in retrospect, if not anticipated in advance. Democratic National Committee chairman Tom Perez (2017) pronounced via Twitter, “We won in Alabama and Virginia because #BlackWomen led us to victory. Black women are the backbone of the Democratic Party, and we can’t take that for granted. Period.”

How black voters came to determine the outcome of the Alabama Senate race became both an engaging and an important story to tell. The near-unanimous black support for Jones came with turnout among black voters that far surpassed predictions. Indeed, the New York Times reported in the weeks before the election that six out of ten black voters were unaware that the election was even scheduled to take place. Analysis after the election, however, revealed that black turnout had been subsequently fueled by relentless on-the-ground mobilization efforts of black organizations and black social networks. In its postelection coverage, the Times gave this vivid description of the role black social networks played in getting out the black vote:

The word traveled, urgently and insistently, along the informal networks of black friends, black family and black co-workers: Vote. Joanice Thompson, 68, a retired worker at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, scrolled Tuesday through the text messages on her phone from relatives reminding each other what needed to be done. Byron Perkins, 56, a trial lawyer, said his Facebook feed was clogged with photos of friends sporting the little “I Voted” stickers given out at polling places. Casie Baker, 29, a bank worker, said her family prodded and cajoled and hectored each other until the voting was done. (Faussett and Robertson 2017)

Black churches had also provided space for Jones to appeal to black voters on Sundays leading up to the election, and reports indicated that there were significant mobilization efforts by local NAACP chapters and other black political organizations (Faussett and Robertson 2017).

Steadfast support for the Democratic Party by black Americans that defies standard political expectations—such as that on display in the 2017 Alabama Senate race—is the subject of this book. The unique social doing of politics among black Americans, whereby blacks’ high degree of social interconnection and interdependence creates unique racialized social incentives for black political behavior, will be our focus. Through the lens on modern black politics we offer, Jones’s victory over Moore may not end up looking completely predictable, but we contend that it will not look politically unusual.

Among black Americans, support for the Democratic Party is a well-understood behavioral norm with roots in black liberation politics. Nonetheless, individual black Americans face a range of incentives—some of them increasing over recent decades—for abandoning the common group position of Democratic Party support.

In short, what we offer is a theoretical framework for understanding how black Americans as a group have succeeded in solving a basic sociopolitical dilemma: how to maintain group unity in political choices seen by most as helping the group in the face of individual incentives to behave otherwise. We do this by elucidating the process by which black Americans have produced and maintained their overwhelmingly unified group support for the Democratic Party in the post–civil rights era. Ours is a social explanation of constructed black unity in party politics that centers on the establishment and enforcement of well-defined group expectations—norms—of black political behavior. We contend that among black Americans, support for the Democratic Party is a well-understood behavioral norm with roots in black liberation politics. Nonetheless, individual black Americans face a range of incentives—some of them increasing over recent decades—for abandoning the common group position of Democratic Party support. Yet the steady reality that black Americans’ kinship and social networks tend to be populated by other blacks means they persistently anticipate social costs for failing to choose Democratic politics and social benefits for compliance with these group expectations. Within this framework, then, in-group connectedness provides not just a salient racial self-concept or informational cues but also social accountability as a constraint on black political behavior. We refer to this process by which compliance with norms of black political behavior gets enforced via social sanctioning within the black community as racialized social constraint in politics. It is this process within black politics that we empirically illuminate and assess—the same one that featured in the Times coverage of how on-the-ground mobilizing of black support delivered the first Democratic senator from Alabama in decades.

Why Black Democratic Unity Is a Question

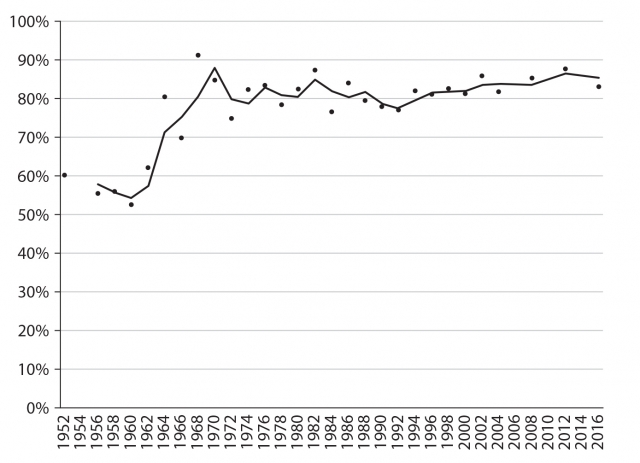

That black Americans are remarkably unified in their support for the Democratic Party, and have been since the mid-twentieth century, seems a rather straightforward fact of American politics. It is a rather simple one to illustrate, as we do in Figure 0.1 with data from the American National Election Studies (ANES) surveys from 1952 through 2016. By the late 1960s the ANES data placed identification of black Americans with the Democratic Party in the neighborhood of 80 percent. It has remained in that neighborhood ever since. The coincidental timing of such stark black alignment with the Democratic Party and the deliverance of civil rights policy by Democratic administrations in the 1960s tempts a simple explanation that those policies made Democrats of blacks. Two important empirical observations complicate the matter.

First, the increasing tendency of black voters to support the Democratic Party predates the civil rights gains of the 1960s. Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal electoral coalition included significantly more black voters than previous Democratic presidential candidates’. That political reality seems to have been made possible in part by Republican Herbert Hoover’s favoritism of the “lily white” faction of the Southern wing of the party—to the particular detriment of the Southern black politicians who had clung to influence in the national party via the “black and tan” faction (Walton 1975). Political scientist Ralph Bunche argued in his report The Political Status of the Negro,prepared in the late 1930s for the study of black Americans sponsored by the Carnegie Foundation and headed by Gunnar Myrdal, that Hoover “spelled the doom of the Black influence in Southern Republican organization.” Among his included evidence were testimonies of blacks who had held positions in the Southern organization, including the first black woman to serve as a Republican committeewoman, hailing from Georgia, who reported, “I have always voted the Republican ticket. In 1932 Walter Brown and Herbert Hoover lily-whited the party in Georgia. I have stomped this entire state for the Republicans—but I wouldn’t do it now” (quoted in Walton 1975, p. 163). And Eric Schickler (2016) has shown that reliable black partisan preferences for Democrats—not just votes swung in their direction—had begun to consolidate by the late 1940s. In other words, the civil rights politics of the 1960s may have crystallized black Democratic partisanship, but they can’t stand alone as the political driver.

Second, in the years since the civil rights gains that supposedly defined black partisanship as Democratic, black Americans have grown more politically and economically diverse. This has surely provided new incentives to abandon the centrality of civil-rights-defined group interest in party identification in favor of some other self-interest, ideological, or alternate group position as the basis for partisan defection. That such defection has not occurred, we argue, should be seen as a bit of a puzzle.

Consider, for example, the remarkable growth of business interests within the black community. In the years before the 2008 Great Recession, the number of black-owned businesses in the United States had been growing at an especially rapid rate. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (2011), “From 2002 to 2007, the number of black-owned businesses increased by 60.5 percent to 1.9 million, more than triple the national rate of 18.0 percent.” This prompted Thomas Mesenbourg, the deputy director of the U.S. Census Bureau at the time, to issue a statement saying, “Black-owned businesses continued to be one of the fastest growing segments of our economy, showing rapid growth in both the number of businesses and total sales during this time period” (U.S. Census Bureau 2011). These black business owners likely experience a tension between their desire for the expanded tax relief policies promoted by the Republican Party and its candidates and the Democratically endorsed social justice and welfare programs that disproportionally benefit the black community but rely heavily on tax revenue.

With growing heterogeneity in black economic interests, we might reasonably expect growing partisan heterogeneity… . And yet [blacks] generally have not left the Democratic fold.

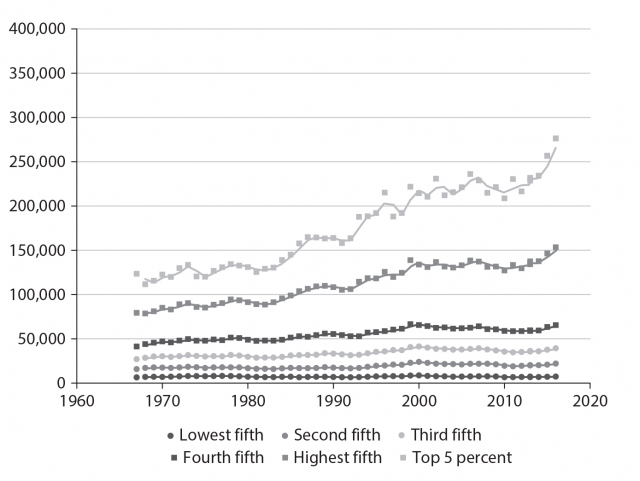

The last forty or so years have also witnessed the emergence and rapid growth of income inequality within the black community. Figure 0.2 illustrates this reality with income data from the U.S. Census. When the Civil Rights Movement made its greatest national policy gains, income inequality across black households was decidedly modest. In the 1970s, the difference between the average household income of those in the top fifth of black households and those in the bottom fifth was about $71,000 in 2016 dollars. In the late 1980s, however, incomes of blacks in the upper percentiles began to grow rapidly. By 2016, the difference in the average household income of those in the top fifth of black households and those in the bottom fifth had grown to about $145,000. The pull of economic inequality is even starker when looking at the top 5 percent of black households. From the late 1980s to today, incomes in that stratum more than doubled, moving from about $125,000 in 1981 to about $275,000 in 2016. Meanwhile, blacks in the lower percentiles experienced little or no meaningful change in yearly household income over this time period. The point: when black America consolidated a voting bloc behind the Democratic Party in the 1970s, its economic interests, at least as measured by income, were decidedly more uniform than they are today. With this growing heterogeneity in black economic interests, we might reasonably expect growing partisan heterogeneity. Those blacks in the upper stratum, who stand to benefit most from growing income inequality, it seems, should eventually see some personal benefit in supporting Republican efforts to promote policies that would expand government support for business opportunities or reduce taxes on the wealthy. And yet they generally have not left the Democratic fold.

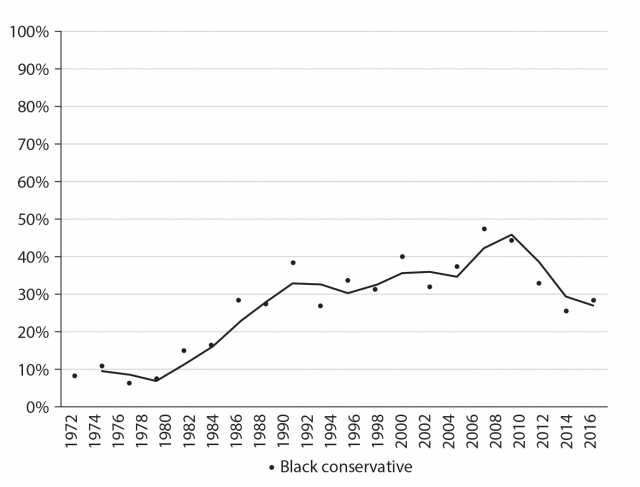

Growing diversity within the black community is not limited to economics. The post–civil rights era has also seen a noticeable increase in ideological conservativism among black Americans (see Philpot 2007, 2017; Tate 2010). Figure 0.3 illustrates this rise via the percentage of blacks identifying as conservative on the standard seven-point liberal-to-conservative ideological self-identification scale from the ANES. According to ANES surveys, in the early 1970s less than 10 percent of blacks identified as politically conservative. By the 2000s nearly 50 percent of black Americans described themselves as such. Although a noticeable decline in black conservativism using this measure of ideology has emerged in recent years, the ANES still estimates that nearly a third of blacks identify as conservatives. And yet partisan identification changes to align ideology with party among blacks have not followed (Philpot 2017).

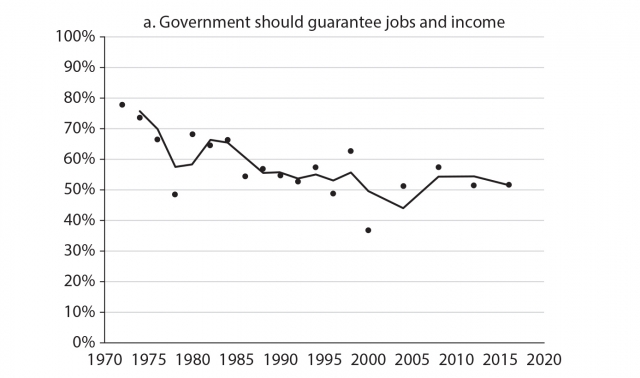

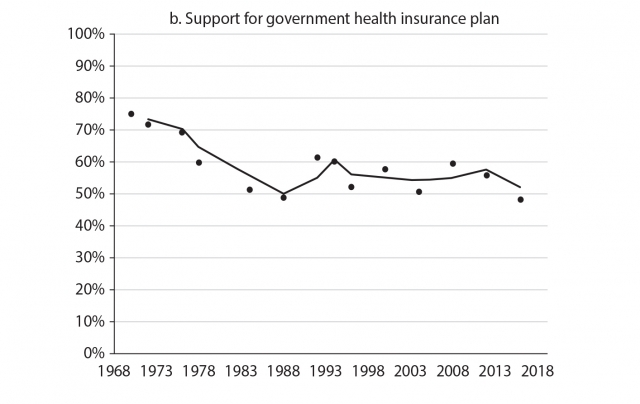

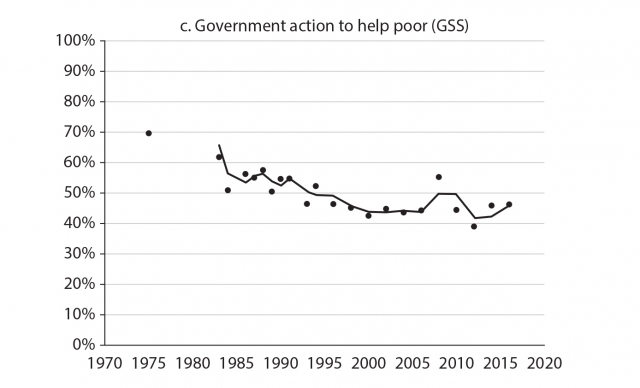

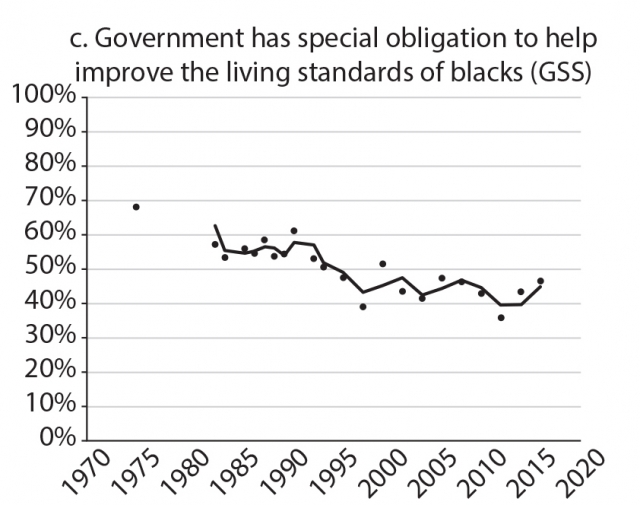

When it comes to policy, the rightward shift in black political attitudes appears even more enduring. We illustrate this point in Figures 0.4a–d with data from both the ANES and the General Social Survey. A significant majority of blacks in the 1970s backed some form of government-sponsored redistributive policy, such as government health insurance, aid to the poor, or a government-sponsored guaranteed jobs and income program. The survey data show that between 70 and 80 percent of blacks supported each of these programs in the early 1970s, as Democratic partisanship solidified. By the 2000s black support for each of these initiatives had fallen off sharply.1 In 2004, for example, only 51 percent of blacks stated that they would support a government-sponsored guaranteed jobs and income program. Similarly, only 51 percent of blacks supported a government-sponsored health insurance program, and only 43 percent of blacks supported government efforts to help the poor.

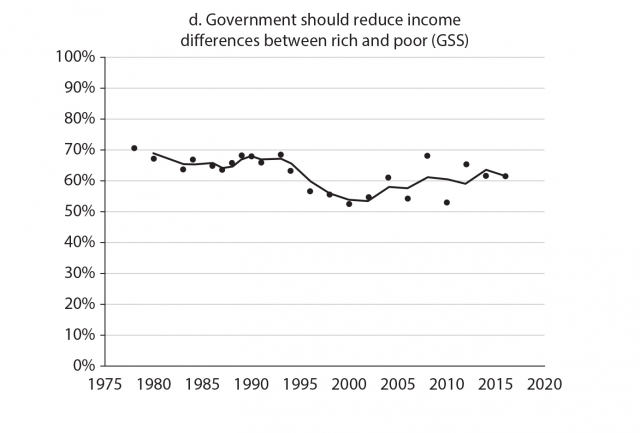

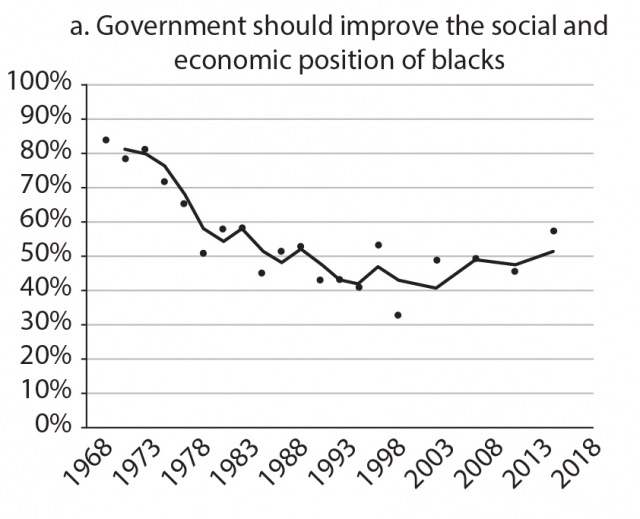

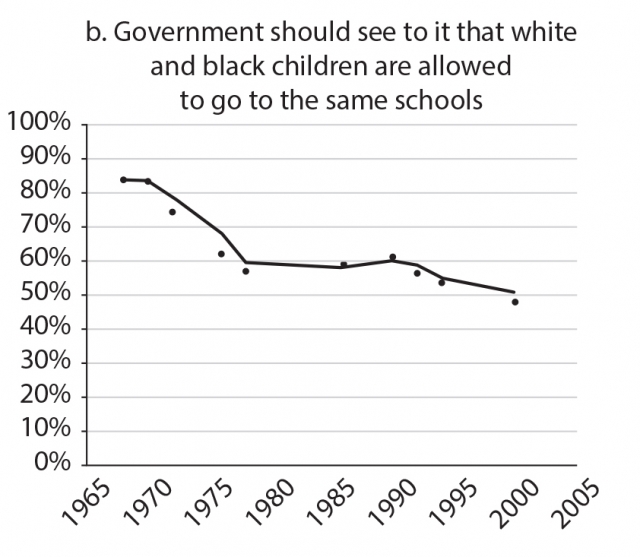

Importantly, this conservative shift in black policy positions also extends to racial issues. Again with data from the ANES and the General Social Survey, Figures 0.5a–c document a clear shift away from the government intervention priorities that characterized the civil rights policies of the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1970s, black Americans overwhelmingly felt that government intervention was necessary to solve racial inequalities. In the early 1970s, over 80 percent of blacks supported government programs meant specifically to improve the social and economic position of blacks. Well over 80 percent of blacks in the early 1970s also felt that the government should be more active in integrating schools. By the 1990s, however, support for these initiatives had dropped off dramatically. In 2000, only about 50 percent of blacks supported government efforts to integrate schools, and today only about 50 percent of black Americans support government assistance programs targeted specifically at racial minorities. The contemporary divisions among blacks on racial issues also extend to less governmentcentric issues, such as affirmative action, where surveys regularly show that over 30 percent of blacks oppose racial preferences in hiring and college admissions.

This rather dramatic rightward shift in black political attitudes over the last half century might be explained, as some have argued, by the incorporation of black political leaders into mainstream politics, which has helped to push blacks away from the extreme liberal positions of the civil rights era by shifting their attention to mainstream political disagreements (Tate 2010). Or perhaps this conservative shift is the product of the economic prosperity experienced by those blacks who have benefited from the rising income inequality over the last several decades. Whatever is responsible for moderating black political beliefs in the 1980s and 1990s, our contention is that the politically remarkable observation is that this conservative shift does not seem to correspond to changes in black party identification.

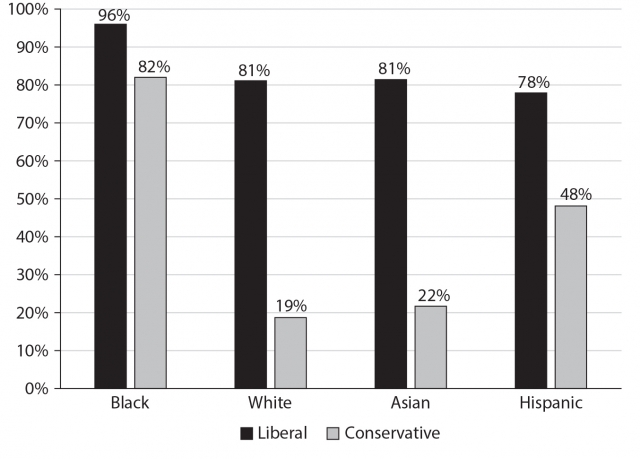

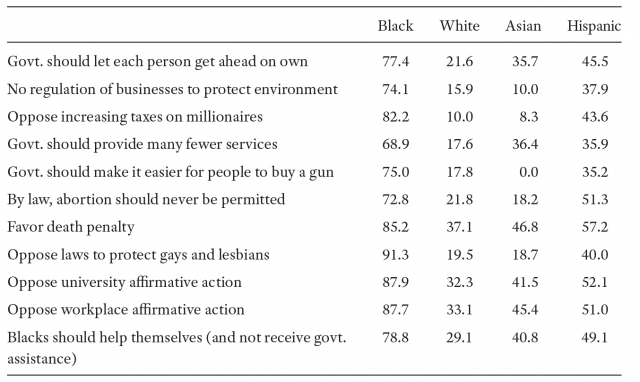

That the increasing political diversity among black Americans has resulted in a unique distance between political attitudes and partisanship is a point we underscore by comparing blacks with other ethno-racial groups using data from the 2012 ANES survey. Figure 0.6 shows group differences in the percentage of self-identified liberals and conservatives who also identify as Democrats. The differences in rates of Democratic Party identification between black conservatives and conservatives of other ethno-racial groups are striking. While only 19 percent of self-identified white conservatives, 22 percent of Asian conservatives, and 48 percent of Latino conservatives identify as Democrats, an overwhelming majority—82 percent—of self-identified black conservatives identify as Democrats. In fact, the level of Democratic Party identification among black conservatives equals that of white liberals. Table 0.1 shows a similar pattern of relative difference in Democratic partisan identification by conservative issue positions. Just as with the self-identified conservative ideology measure, the vast majority of black issue-conservatives identify as Democrats, while those in other racial groups do not. Across eleven different measures of issue conservativism, the percentage of blacks identifying with the Democratic Party never dips below 70 percent. Compare this with white issue-conservatives, whose rate of Democratic Party identification never exceeds 37 percent. Even blacks’ conservative beliefs on racial issues fail to correspond to eroded identification with the Democratic Party. Nearly 90 percent of blacks who stated that they oppose affirmative action programs nonetheless identified as Democrats.

Why hasn’t growing conservativism—even on racial issues—pushed blacks into the ranks of the Republican Party? Surely, blacks must sense the tension between their conservative political beliefs and their Democratic Party support. The question thus becomes how, exactly, have blacks maintained Democratic Party unity since the civil rights era? Answering that question is our aim.

Racialized Social Constraint and Black Democratic Party Identification

To make sense of the enduring partisan unity of black Americans, we argue, necessitates a framework that better incorporates their social groupness into our understanding of their political groupness. The idea that blacks form a political group because of collective interests defined by the American racial order is not a novel one. Nor is the idea that to make demands on government effectively, groups—such as black Americans—that have historically lacked economic and political power often come to rely particularly on forms of mass political action meant to convey unity in political preferences (Omi and Winant 1996). African Americans have often employed mass protest, boycotts, public demonstrations, and bloc voting as a means of conveying a sense that group members are unified both in their political positions and in their demands for government responsiveness to specific group concerns (Browning, Marshall, and Tabb 1984; Gillion 2013; McAdam 1982). And for black Americans this “solidarity politics” has proved to be an effective means of challenging white supremacy (Shelby 2005). From the enormous crowds that showed up in 1963 for the March on Washington to blacks’ nearly unanimous electoral support for the candidacy of the first black person nominated by a major political party for president, solidarity politics have conveyed to government and the larger American population the message that black Americans not only speak with one voice but are prepared to act collectively if their concerns are not addressed.

Essential to the effectiveness of this solidarity politics strategy is the ability of the group to credibly convey that common concerns are widely valued by group members because it is that value that signals political commitment (McConnaughy 2013). The effectiveness of solidarity politics, in other words, rests on the credibility of the threat that the group will mete out its collective power. This logic for black politics was rather clearly articulated by Stokely Carmichael and Charles Hamilton in their 1967 guide to black political empowerment, Black Power. As quoted in Shelby (2005, p 101), Carmichael and Hamilton explain, “The concept of Black Power rests on a fundamental premise: Before a group can enter open society, it must first close ranks. By this we mean that group solidarity is necessary before a group can operate effectively from a bargaining position of strength in a pluralist society.”

Defection by group members, however, is a constant threat to solidarity politics that must be managed. The challenge to black politics from defection or shirking by group members can be seen rather clearly in Martin Luther King Jr.’s final speech, where he implored the black community in Memphis to show up for a scheduled march in support of striking sanitation workers. King exhorts, “When we have our march, you need to be there. If it means leaving work, if it means leaving school—be there. Be concerned about your brother. You may not be on strike. But either we go up together, or we go down together” (Stewart 2018). King’s entreaty evinces the central tension: in the grander scope of politics, only unity will deliver gains for subordinated groups, but defection for the sake of immediate individual interests is a constant threat to the group position and impairs the doing of politics in the interest of the group.

The efforts of white Americans to segregate black Americans from larger American society have made black Americans uniquely socially integrated with and reliant on each other. Closed off from white social institutions such as schools, colleges, fraternal organizations, and churches, black Americans built their own indigenous institutions.

We argue that black Americans’ capacity to resolve the defection conundrum is born of the same phenomenon that has created their need for political unity: the American experience of racial apartheid. The efforts of white Americans to segregate black Americans from larger American society have made black Americans uniquely socially integrated with and reliant on each other. Closed off from white social institutions such as schools, colleges, fraternal organizations, and churches, black Americans built their own indigenous institutions. Cordoned off from white neighborhoods by policies and social intimidation practices, black Americans built their own communities. Antimiscegenation laws and social denigration from white society further ensured that black Americans’ kinship and social networks have remained characterized by a high degree of racial homophily. In short, black Americans remain remarkably socially interconnected with each other and segregated from white Americans. And in this social reality, we argue, are the tools for a black politics maintained by racialized social pressure—what we term racialized social constraint.

Racialized social constraint is a process of enforcing the norms of black political behavior. It includes well-defined, racially specific social rewards and penalties, which are used to compel compliance with group-based expectations of political behavior. Even in the presence of individual incentives to do otherwise, the unambiguous nature of black political expectations and the particular value assigned to the social consequences of defection from versus compliance with this normalized group behavior place significant constraints on the political behaviors of black Americans. Social pressure from other blacks is the key element of this process. For an individual whose social existence rests within the black community, the cost of defecting from the understood norms and practices of that group is greater when it is understood that other members of that group, in particular, might be aware of this defection. In other words, racialized social constraint rests not on blacks concerned with whites questioning their blackness but rather on the social costs to be paid when other blacks question their commitment to or standing within the racial group. Well-established norms can also be internalized into beliefs in black solidarity. Thus, racialized social constraint functions beyond external social pressure, through an attitudinal acceptance of the importance of group solidarity. Both these mechanisms work to increase individual-level commitment to group-based norms of political behavior, preventing self-interested behavior that would undermine the group’s capacity to leverage unity as political power in the collective interest.

Specific norms of black political behavior exist, we argue, because black Americans have over time been able to connect certain group-benefiting political behaviors with racial in-group identity. Through the association of certain behaviors with prototypical or idealized representations of blackness (Laird 2019), those behaviors come to be defined as “good” black political behaviors. And central among these norms in the post–civil rights era has been that of Democratic Party identification. Maintenance of Democratic identification as an in-group norm is surely aided by its informational basis—that blacks “are Democrats” is repeated as fact through common descriptive information, such as election returns that describe over 90 percent of black voters casting ballots for the Democratic presidential candidate. But there is more than a descriptive norm at work. Appeals that suggest that other black Americans “died for your right to vote” and depictions of black Democratic politicians, such as Barack Obama, that describe them as “role models” for black youths are common elements of black political communication. Given this normalization of black support for the Democratic Party, we contend that identifying with and voting for the Democratic Party and its candidates have come to be understood by most black Americans as in-group expected behaviors that individual blacks perform in anticipation of social rewards for compliance and sanctions for defection. Enforcement comes through social ties and black institutions, which help to define the boundaries of black social and political behavior and add institutional weight to black social connections (Cohen 1999; Dawson 1994; F. C. Harris 1994; Harris-Lacewell 2004; Mckenzie 2004).

What the Racialized Social Constraint Framework Is—and What It Is Not

Racialized social constraint as an explanation for black partisan unity is a move away from explanations of black politics that are focused almost exclusively on individual dispositions and toward one that truly incorporates social dynamics. To this point, most explanations of black partisan political behavior have focused on the roles that individual dispositions play in shaping or constraining black political beliefs and actions (see Dawson 1994; Gurin, Hatchett, and Jackson 1981; Philpot 2017; Shingles 1981; Tate 1991; Verba and Nie 1972). Among these have been individual dispositions, such as ideology, and individual-level group identity considerations ranging from simple affective closeness to beliefs in common fate, group consciousness, and solidarity. While not arguing that these attitudes are unimportant to black political decision making, we seek to resolve important empirical and theoretical difficulties.

The currently dominant attitudinal explanation of black support for the Democratic Party suggests that even blacks whose ideological, class, or individual interests do not align very well with the party’s platform will nonetheless identify as Democrats as a result of an understanding that the Democratic Party is more likely than the Republican Party to represent the interests of blacks as a group (Dawson 1994; Philpot 2017; Tate 1993). One central difficulty in this model is that what “group interest” is and how it gains and maintains a common definition across a diverse group remain vaguely specified. What, exactly, is “black” group interest in the post–civil rights era (see Frymer 1999)? Even considering the role that Democrats played in securing black civil rights protections in the 1960s, it is not as if Republicans have not tried to position themselves as a party that represents black interests—or at least some interpretation thereof. Many of the limited government, self-help, personal responsibility, and moral arguments offered to blacks by Republicans are explicitly couched in terms of black identity politics, including black empowerment and racial group uplift. Blacks who do identify as Republicans have made concerted efforts to convince other black Americans that it is in both the individual and the group interests of blacks to support the Republican Party (see Fields 2016). And still, even most blacks who share many of the Republican Party’s conservative political positions remain solidly in support of the Democratic Party. Existing dispositional models of black politics do not tell us why and how that is so. Our framework seeks to do just that.

Broadly, the basis of group-identity models of politics is the observation that humans are by nature social and that group membership and identification help to fulfill a basic need to belong (Tajfel and Turner 1979). But groups provide more for individuals than simply psychological belonging—they structure both daily experiences and access to resources and power. Thus, understanding the implications of group memberships for politics necessitates a set of analytical tools that clarify how the social workings of specific group memberships translate into individual political behaviors. Our racialized social constraint framework takes the specificity of the black American experience—with its history of slavery and racial segregation—and spells out its implications for the doing of group-based politics by individuals. It integrates not only the common set of beliefs but also the common practices and social relations that define what it means to be a black person in America (Franklin and Moss 1994). It makes the structure of the lived experience of blackness central to the politics of black Americans. Fundamentally, our framework seeks to better explain how the social experience of blackness translates into the homogeneity we observe in black partisan identification and behaviors.

As much as it is important to say what racialized social constraint is, it is equally important to clearly articulate what it is not. We are not suggesting that black Americans are mindlessly following the dictates of the group. Quite the contrary. Unlike many dispositional explanations of black political behavior, which suggest that group unity stems from some sort of affective tie to the racial group or from black Americans not making individually optimal decisions (Dawson 1994), ours is a rational explanation of black political decision making. Adherence to group norms of political behavior is produced through black Americans making realized trade-offs between their ideological or individual self-interests and the potential for racialized social consequences that might accrue to them personally as the result of their decision. Importantly, social sanctions are dealt out to group members for defection from political choices understood to be in the interest of the group, and social rewards are given for compliance with these expectations. Indeed, we will show in later chapters how racialized social constraint produces compliance not with just any political behaviors but rather with those that have specific group-interest meaning.

Our account also does not suggest that black Americans lack any real agency in deciding their own partisanship. While deviating from in-group expectations can have real social costs for black Americans, the racialized social constraint model still implies that black Americans make choices about the trade-offs they are willing to accept between social costs and rewards, on the one hand, and self-interests, on the other. We demonstrate empirically that although black Americans are highly responsive to racialized social pressure, many nonetheless freely defect from group-based expectations. For some black Americans, defection is enabled by having more racially diverse social connections. Others appear to defect simply because they more greatly value their individual ideological or material self-interests over any social cost of defection. The modern black experience of racialized social constraint certainly implies trade-offs to navigate. It does not, however, engender a coercive system meant to suppress individual choice and agency entirely.

Lastly, despite our invocation of unique features of black groupness, we offer this framework as an adaptable tool for the general explanation of group-based behavior. Its utility in explaining the politics of other social groupings depends on the extent to which there are well-defined norms of political behavior and socially homogeneous institutions and networks that enable the maintenance and enforcement of those norms. As we discuss the conditions necessary for our racialized social constraint model to hold, we highlight how groups such as Southern whites, white evangelical Christians, trade union members, and certain localized racial and ethnic groups exhibit elements of social constraint similar to those exhibited by black Americans. In the concluding chapter of the book, we discuss in some detail how our framework applies to some of these groups.

Making Racialized Social Constraint Visible

Our central task in this book is demonstrating how a distinct set of social processes, embodied in our racialized social constraint explanation, constrains black behavior and prevents defection from the Democratic Party. Demonstrating this is not simple. Given that nearly all black Americans identify as Democrats—and have for some time—isolating the conditions under which this identification is created and maintained is empirically difficult. There simply is not much variation in the outcome that can be used to observe under what conditions black Americans identify with the Democratic Party and under which they do not. Our approach resolves this difficulty by adopting a fundamentally counterfactual perspective. To understand and assess how blacks’ high level of Democratic partisanship is maintained, we first identify the social and political conditions that might result in lower levels of black Democratic Party support. Then we create those conditions and observe what happens. In short, by offering black Americans, under controlled conditions, realistic incentives to defect from the Democratic Party and social situations in which they can feel free to defect, we find some black Americans significantly less likely to identify with and behaviorally support the Democratic Party. That is, by providing conditions that are less likely to occur “in the real world,” we can observe how the “real-world” conditions are effectively maintaining the distribution of black Democratic identification and support.

The experiments we conducted give us causal evidence of how racialized social constraint produces partisan unity among black Americans. By operationalizing racialized social constraint through a set of constructed racialized social interactions, to which we randomly assigned black American study participants, we were able to directly test its ability to constrain partisan defection. Our experiments cover a broad range of manifestations of the racialized social constraint concept. We assess how even everyday existence in a racially homophilic environment imposes constraint by observing the effect of the simple presence of another black person bearing witness to a political behavior that implies a choice between supporting the group interest and supporting a self-interest. We gain insight into the constraining effects of black institutions by observing the effect of study participants being made aware that their choices in a group-interest versus self-interest situation will be made known through the student newspaper of a historically black university. Each experiment offers a unique piece of empirical leverage. Together they tell a coherent story of racialized social constraint as a fundamental force in the production of black partisan unity.

While the experiments are the core of our empirical assessment of racialized social constraint’s causal effects on black political behavior, we embed them in the context of relevant descriptive realities of the black American political experience. The plausibility and explanatory value of our framework depend on a range of descriptive facts—from the extent of ongoing racial homophily in the social environments of black Americans to black Americans’ basic awareness of what other blacks do and expect of them in the realm of partisan politics. Thus data drawn from the “real world” of the black American experience are just as much a part of the empirical case we offer as are the results of experiments wherein we construct the details of our study participants’ experiences.

Outline of Book

In the next chapter, we offer a detailed explanation of our racialized social constraint model of black political behavior. As an answer to our central question of the role of black unity in partisan politics, we argue that black support for the Democratic Party has over time become a normalized form of black political behavior for which blacks actively hold one another accountable. In developing this argument, we first review the relevant literature on African American political behavior and discuss how many of the insights gained from this research point to the importance of group-based expectations in ensuring compliance with group norms of black political behavior. We then engage the microfoundations of black political behavior, building on insights from mainstream political behavior and social psychology to identify the precise mechanism by which black partisan homogeneity is likely maintained. Our focus is on how various incentives for compliance with group norms and sanctions for defection from these norms result in the maintenance of black political unity. We also discuss the unique way that these norms relate to black identity, building on insights from the psychological theory of role identities. All of this leads to a set of general expectations for what we should observe if our framework for understanding black political behavior holds.

In Chapter 2 we begin with a discussion of the social and political circumstances that have necessitated black political unity, norms of black political behavior, and the emergence of racialized social constraint. Placing its historical origins in slavery, we discuss how racialized social constraint has developed from a tool for navigating the complicated social and political world of forced labor communities into an instrument for facilitating racial group-based collective action politics among black Americans. We connect norms of racial group constraint formed under slavery to mechanisms for mobilizing blacks into the protest activities of the 1960s Civil Rights Movement and tools for facilitating specific forms of engagement in modern electoral politics. From the combined insights provided by our historical review of black Americans’ efforts at collective action and our racialized social constraint model, we derive specific predictions of how racialized norms of political behavior constrain black partisan support in modern electoral politics. Finally, we highlight two basic facts that speak to the explanatory potential of our framework. First, we show that black Americans indeed share a common awareness that most other blacks regularly support Democratic candidates. Second—and, we think, more telling—we show that black Americans report not only that they are regularly solicited by friends and family to support the Democratic Party but also that they are concerned about the social consequences of friends and family finding out if they were to choose not to support the Democratic Party and its candidates.

Building on research that focuses on the social and cultural underpinnings of political preferences, we take racial segregation and the isolation of African Americans in racially homogeneous communities to be crucial in ensuring the continued effectiveness of racialized social pressure at constraining black political behavior. Thus, Chapter 3 offers our empirical assessment of the connection between racial homophily in black social networks and homogeneity in black party support. We show a strong link between racially homogeneous social networks and black Democratic Party support. Among our findings is that the more racial in-group members within a black person’s close social network, the more likely that individual is to identify as a Democrat. Further, the composition of networks seems most predictive among those blacks who have ideological incentives to defect from the norm of Democratic support. Among black conservatives, we find, those with more racially diverse social networks are more likely to defect from the norm of supporting the Democratic Party.

In Chapter 4 we begin to dig into the process by which racialized social constraint works to inhibit the defection of black Americans from the norm of Democratic Party support. Empirically, we take advantage of the social interactions within survey interviews—between black respondents and either black or non-black interviewers—as a window into exactly how racialized social constraint works to inhibit blacks’ defection from the Democratic Party. Pooling more than thirty years of face-to-face survey data and twenty years of phone survey data, we show that the simple presence of a black interviewer exerts considerable pressure on black respondents to conform to the norm of supporting the Democratic Party. Not only do we find that black respondents express significantly greater identification with the Democratic Party when in the presence of a black interviewer, we further demonstrate that the effect is most pronounced among those blacks who have the greatest incentive to defect from the norm of Democratic Party support: black conservatives.

In Chapter 5 we move from racialized social constraint’s influence on the simple expression of black party identification to its ability to increase political action in support of the Democratic Party and its candidates. To demonstrate the existence of an in-group norm of active support, we turn once again to data about the race of the interviewer. These data show that the mere presence of another black person—even a complete stranger—leads black Americans not only to express an increased desire to act in support of Democratic candidates before an election but also to overstate their actual involvement in campaign activities following the election. We then push deeper into the causal process of racialized social constraint using a lab-in-the-field experiment that enables us to directly test the effect of racialized social pressure on blacks’ willingness to engage in political action. Using the behavior of contributions to the Obama campaign as a black group-norm-consistent behavior, and using personal monetary incentives to defect from this norm to induce a self-interest conflict, we vary whether black study participants must make their choice in front of another person who has made his or her own political choice clear, as well as whether that person is a racial in-group member. We find that, indeed, social pressure from other blacks uniquely reduces self-interested behavior and results in greater group-norm-consistent political behavior. Importantly, we also show that social pressure from other blacks only works to increase group-norm-consistent behavior. It does not encourage defection.

Chapter 6 takes up black social institutions as central locations where in-group political norms are defined and propagated. We outline a basic history of black social institutions, including how their creation was a direct response to the denial of access to white spaces. We note the importance of these institutions as sites for in-group political discourse and the enforcement of norms. These institutions are places where blacks are reminded of group expectations. Using survey data, we demonstrate the frequency with which blacks Americans interact within black institutions. Our analysis shows that black institutions continue to be centers for daily engagement, reinforcing black social ties. This also, of course, makes them sites wherein black Americans are likely to anticipate social sanctions for their political behaviors. Indeed, we show that participation or membership in black institutions is related to greater adherence to norms of black political behavior, including Democratic partisan identification. We then turn to another lab-in-the-field experiment to directly test the power of black institutions to facilitate racialized social constraint. Using a prominent black institution, a historically black university, to implement racialized social constraint, we find that black institutions can indeed be especially effective as conduits for the enforcement of compliance with norms of black political behavior.

In the final chapter, we examine the broader implications of this research, both empirical and normative. We discuss the potential for our theoretical framework to further understanding of the political behavior of other social groupings in America. In particular, we consider how our theory of racialized social constraint could explain the behavior of Southern whites in their modern allegiance to the Republican Party. We also consider the framework’s applicability to understanding the political homogeneity of localized racial groupings—where ethno-racial political unity might not be possible on a national scale but should be expected under local circumstances. If the foundational mechanism of political power through unity is that identified by our framework—coracial social ties—then desegregation and the loss of black institutions are a fundamental challenge to the doing of black liberation politics. We discuss what this might mean for the future of black politics. In so doing, we also engage arguments about the harms of coracial policing and weigh how to think about balancing those concerns against the reality that the political unity that has consistently enabled black political power relies on a process of social sanctioning. Finally, we consider the questions future research might answer by engaging and applying our theoretical framework and chart a course for future progress.

This article is an excerpt from Steadfast Democrats by Ismail K. White and Chryl N. Laird.