From Greek rebels, American settlers, and Brazilian abolitionists in the nineteenth century to anticolonial Africans and Zionists in the twentieth, nationalists have confronted a crucial question: Who has the “right to have rights?” A World Divided tells these stories in colorful accounts focusing on people who were at the center of events. And it shows that rights are dynamic. Proclaimed originally for propertied white men, rights were quickly demanded by others, including women, American Indians, and black slaves.

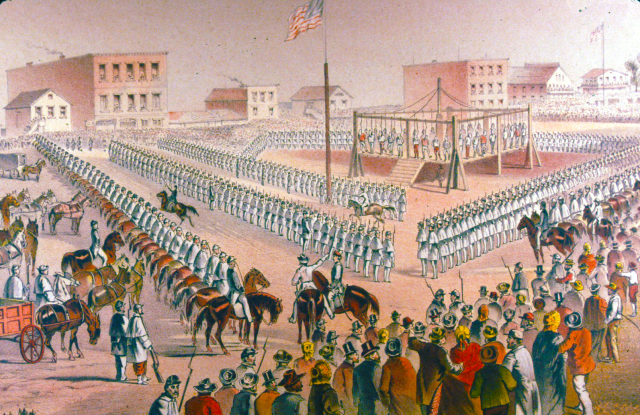

The book jacket depicts the largest mass execution in American history—38 Dakota Sioux Indians—during the Civil War. None other than President Abraham Lincoln approved the executions. Why did this particular episode in American history seem fitting to illustrate A World Divided’s argument?

EW: Because it shows that human rights in the age of nation-states—the age we still live in—are always double-edged. The Euro-American settlers who came to Minnesota quickly acquired all the rights we associate with American democracy. They didn’t even have to be citizens to vote. All they had to do was declare their intent to become citizens and they could go to the local courthouse or school and participate in elections. They came to the United States for all the same reasons that immigrants today cross the border. They sought—and seek today—a better life, whether that means fleeing violence, religious and political persecution, or poverty, or all at the same time.

But the rights that Euro-Americans won in Minnesota was fundamentally dependent on the displacement of Native Americans. In 1862, in the middle of the Civil War, the Dakota Sioux rose in rebellion against the loss of their lands and other injustices they suffered at the hands of both settlers and the US government. In the middle of the Civil War, when the Union army’s fate was at a low point, the federal government diverted troops and other resources to the state to defeat the Sioux. From President Lincoln on down, government officials recognized how crucial it was to defeat not just the Confederacy, but the Sioux as well if the United States was going to survive and flourish as a unified nation-state from coast to coast. That also meant the defeat of an Indian conception of communal ownership of the land and the triumph of the Euro-American notion regarding the sanctity of individually-owned, private property.

Rights for some, displacement and killings of others—that is the dilemma of human rights in the age of nation-states.

We think of people like Abraham Lincoln, the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and Nelson Mandela as “heroic actors”—extraordinary people who advance human rights almost entirely on their own. But you say that’s not how we actually gain rights. How does it actually happen?

EW: Yes, there are heroic individuals and they play important roles in securing human rights. That includes some lesser-known women as well, like the Brazilian Bertha Lutz, about whom I write. But these individuals operated within powerful social movements. Even that does not suffice. I argue that we get human rights advances through the often fleeting confluence of social movements, state interests, and the concerns of the international community.

One example: the Greek rebels of the 1820s, who sought independence from the Ottoman Empire, were considered a major nuisance by the Great Powers of the day, Great Britain, Russia, the Habsburg Empire, and France. But because the rebels would not give up and the Ottomans were unsuccessful in suppressing them, the Great Powers reluctantly interceded. They wanted, above all else, stability in the Eastern Mediterranean (though Russia was also looking to expand its influence). In the end, the Great Powers reluctantly conceded to the establishment of a Greek nation-state and, eventually, a constitution with some rights for propertied men. The combination of a powerful social movement, namely, the Greek rebellion, coupled with the actions of prominent Greek statesmen and the concerns of the international community, enabled the human rights advance in the Eastern Mediterranean.

But the Greek rebels were not only heroic liberators. They also massacred Muslims and Jews in the drive to make Greece a nation-state composed exclusively of adherents of the Greek Orthodox Church. As with the case of Sioux Indians in Minnesota, rights for some were coupled with the displacement and killings of others.

Who are some human rights advocates in history that get short shrift, in your opinion? Are there significant groups or figures that just have not gotten the recognition for their efforts as they deserved?

EW: If one thing is true, it is that human rights are dynamic. In the nineteenth century, they were reserved largely for propertied white men. But in that era, and going back to the French, American, and Latin American revolutions that began in the late eighteenth century, many people said, in effect, what about us? If rights are universal—as the revolutionaries of the day proclaimed—what about black slaves, women, factory workers in the early years of industrialization? In the twentieth century, colonized peoples around the world posed the same question to the British, French, Portuguese, and other colonizers (including the US!). If you keep talking about liberty and rights—as they did—why don’t we have national independence and access to rights?

I mentioned Bertha Lutz, who almost single-handedly assured that the United Nations Charter contains a provision for the equality of women and men. In the book I also write about a slave rebellion in Brazil, and the long-running struggle for democracy and human rights in South Korea. The activists in both countries suffered greatly. Americans know about the terrible violence that the Chinese government unleashed on the Tiananmen Square protesters in 1989. But except for Koreans and the few specialists on Korean history and politics, who knows what happened in South Korea just nine years earlier, in 1980? That was when the South Korean security forces, with American support, unleashed a repression even bloodier than Tiananmen, a repression that targeted demonstrators in Kwangju. Eventually, the South Korean dictatorship tumbled, in no small measure because of human rights activism, but also because the US eventually decided that the strong-men dictators it had backed were more trouble than they were worth. No human rights advance comes about easily.

You also argue that human rights issues are complex, because what liberates one group may actually oppress another. What’s a good example of this in recent history?

EW: Palestine/Israel comes immediately to mind. In the wake of the Holocaust (as we now call it), it is hard to see any other solution for the shattered survivors than a Jewish nation-state in Palestine. The force of Zionism in the post-Nazi era and the entire thrust of international politics—the nation-state as the dominant political model of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries—made the foundation of Israel the most likely political outcome. But just as the establishment of the United States as a Euro-American nation-state from the Atlantic to the Pacific depended on the removal and killings of Native Americans, Israel as the Jewish state depended on the removal of nearly 800,000 Palestinians. While there was no single plan for their displacement, leading Zionists had been talking about the removals—what we now call ethnic cleansing—since the 1930s. Zionists could not countenance a country in which Jews would be a bare majority or, even worse, a minority. Everything in the biographies of Zionists argued against that—their revulsion against the minority status of Jews in Europe, their drive to foster a new Jewish culture in Palestine, and, finally, the lived experience and memory of the Holocaust. Israel became a nation-state with human rights for Jews. For Palestinians, the experience was one of displacement and, for those who remained within Israel’s borders, second-class status.

These same dilemmas play out in virtually every chapter of the book, and we still live with the consequences, most obviously and tragically in the on-going conflicts in the Middle East.

What surprised you most about human rights advancements in your research? Was there any individual or group that pushed rights forward that might surprise readers?

EW: I expect that the chapter on the Soviet Union will surprise many readers. People like to believe that the human rights achievements of the post-1945 era were the result of the efforts of liberal states, like the United States, the United Kingdom, France, and others. In fact, at critical moments, they tried to block human rights advances, not always successfully, The United States, for example, adheres to an understanding of human rights as only political in nature, the right to free speech, freedom of religion, and so on. It has still not ratified the international treaty on economic, social, and cultural rights, passed by the UN General Assembly in 1966. While most human rights activists and countries around the world now consider these rights critical to any conception of human rights, the US still argues that social and economic rights smack of communism. We also have not signed on to the International Criminal Court.

In contrast, the Soviet Union from 1945 onward forged an alliance with the countries of the Global South. Together, they pushed forward a human rights agenda that included social and economic rights, decolonization, and self-determination, not just political rights. However deeply repressive the Soviet Union was on its home territory—and I do not neglect at all the repressive and often bloody character of the Soviet regime—in the international realm it was an active proponent of human rights. Its understanding of these issues lay deep in the socialist tradition; they were not just manifestations of Cold War conflict with the West.

What should readers take away from A World Divided?

EW: Human rights are complex, but they remain the best thing we have going for us. They will never be implemented in the total fashion that some activists believe possible. But where they take hold, even partially, they at least offer us the ability to lead more free, more expansive lives. They give us the opportunity to speak out, to assemble, to work and create as we wish. And they protect us from the scourges of arbitrary state power and terrible violence and displacement.

Human rights developed entwined with the nation-state, and so they remain. Nation-states are always exclusive as well as inclusive. They always limit, sometimes violently so, who has the possibility to become a rights-bearing citizen. We see these policies at work all around the world today with nearly 70 million migrants, an almost unfathomable number. The highly restrictive, repressive and even brutal policies enacted on the US’s Southwest border today is only one example of a global trend by nation-states to limit who may become a citizen. That is why I argue in the book that anything that moves human rights protections beyond the nation-state to the international level—international human rights treaties, including the 1951 refugee convention; the International Criminal Court; the newly-ratified treaty on the Crime of Aggression—marks an advance.

Eric D. Weitz is Distinguished Professor of History at City College and the Graduate Center, City University of New York. His books include Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy and A Century of Genocide (both Princeton). He lives in Princeton and New York City.