Poetry Day in the UK is October 3, the perfect time to revisit a lost poem—and its rediscovery by contemporary poets. Gilgamesh is the most ancient long poem known to exist. It is also the newest classic in the canon of world literature. Lost for centuries to the sands of the Middle East but found again in the 1850s, it tells the story of a great king, his heroism, and his eventual defeat. It is a story of monsters, gods, and cataclysms, and of intimate friendship and love. Acclaimed literary historian Michael Schmidt provides a unique meditation on the rediscovery of Gilgamesh and its profound influence on poets today.

Gilgamesh is one of the oldest stories in existence. What’s new and different about your approach to the poem?

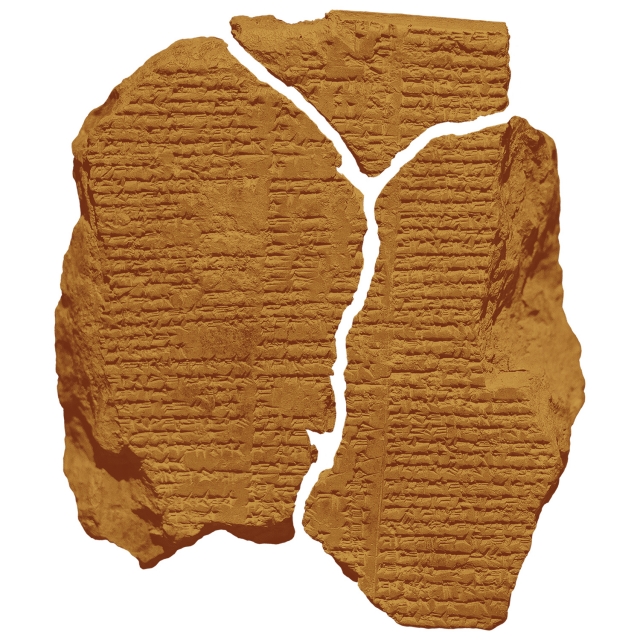

MS: I approach the poem as a work without an author. It was composed over many centuries in different languages and dialects. We are used to thinking about poets and what they might mean, their motives etc. But with Gilgamesh (as, in a sense, with Homer and the Bible) we don’t have an author to turn to. Homer was invented for convenience, to make the poems less alien; and various books of the Bible can be attributed, but despite the brief appearance of a redactor, the still fragmentary text of Gilgamesh is unauthored and is its own, gradually accreting authority, as more bits are found and slotted in and translated. My book is supposed to amuse and at the same time to clarify some of the difficulties of the poem. It’s also about the ways in which, for a century and more, poets have responded to it.

You’ve said before that poetry is less about subject matter, and more about the interesting ways that poets experiment with language and form. So does that hold true for your fascination with Gilgamesh, which is undeniably rich in subject matter?

MS: Gilgamesh, because it is so ancient and so unaccountable, is all experiment. Was it composed for performance, if so in what context? Was it originally written, and then perhaps recited? It is a poem which, however and wherever you approach it, raises questions. What is fascinating in the numerous English translations that exist is how variously it has been read. The absence of a poet, an accountable subjectivity, makes a lot of translator’s feel free to colonise it with their own religious, political, sexual and other concerns. Each appropriation falsifies the suggestive openness of the poem.

What’s the most inventive or exciting interpretation of Gilgamesh that you’ve read?

MS: I like best those versions which are produced with a linguistic challenge in mind, for example to imitate the strange ways in which the language of the original is constructed, to go as far as possible with the poem’s otherness. For consecutive reading, and for the most illuminating notes, I love the Andrew George translation. The book samples most of the main versions and recommends one or two as especially revealing. I like best those which don’t make the idiom of the poem familiar or the characters too cinematic.

Do you have a favorite passage, stanza or line from the poem?

MS: I love the scenes when Gilgamesh and Enkidu slay the wood monster; I love the scene in which Gilgamesh races the sun; and the scene where the hierodule is set out to entice Enkidu into joining the human race – rather erotic in its way. I also like the scenes between Gilgamesh and Enkidu. Gilgamesh proves extremely anxious about his friend’s mortality in ways which are touching, so that in the not quite connected portion of the poem, when Enkidu revisits the world of the living, something very strange and moving occurs. The poem doesn’t easily slot together as a narrative, and its awkwardnesses, its discontinuities, are eloquent.

So—why Gilgamesh? Will it endure the test of time?

MS: It has endured the test of time physically, that is, in bits and pieces sections of the poems have survived, the language has been first reconstructed and then translated. It will survive if it finds a major literary translator, someone with the gumption to make memorable verse out of it. Ted Hughes was very interested in it: his kind of energy would have brought parts of it alive. But there is a danger in considering it as somehow atavistic or primitive. The culture that produced it was immensely resourceful and deeply cultured, and many of its subtleties are still to be unfolded by the scholars and then interpreted by the poets. Andrew George, again, has opened the main gate to the poem.