I needed to pass age sixty before I could write a book about the artist Michelangelo Buonarroti in his seventies and eighties. How else could one understand those nagging aches of the body, the fear that slow but inexorable physical decline would soon be accompanied by mental deterioration, the melancholic realization that one’s diminishing circle of friends and family were either retiring, or worse, dying.

There is no mandatory retirement at my university, yet I am now more than three times the age of those eager, Freshmen students. For many years I did a handstand at the beginning of class; it was my unconventional means of getting the attention of an unruly group of 250 students fixated on their cell phones or on each other. At age sixty, I gave up handstands. I still teach and compete for the limited attention span of the younger generation, and I still write books, competing in the crowded marketplace of ideas.

Having already written a half dozen books and nearly one hundred articles on Michelangelo, you are justified in thinking: “enough is enough.” Time to retire?

Michelangelo never retired. He lived 89 years in an era when life expectancy was age 40. Michelangelo began thinking about dying at 40 and continued to do so for the next fifty years. While he enjoyed good health, he suffered from kidney stones which he decried as “the cruelest thing.”

In 1546, after some forty years of pleas, threats and cajoling by the family of Pope Julius II, Michelangelo finally installed in San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome the tomb of the long-dead Pope, with the magnificent marble Moses. Months later, his two closest friends—the poetess, Vittoria Colonna and his boon companion, Luigi del Riccio—suddenly died. Grief overwhelmed him. Given that he was older than both those dear friends and the fact that he had finally completed his most important artistic obligation, Michelangelo contemplated returning home to Florence and to a well-deserved retirement. After all, he was 71.

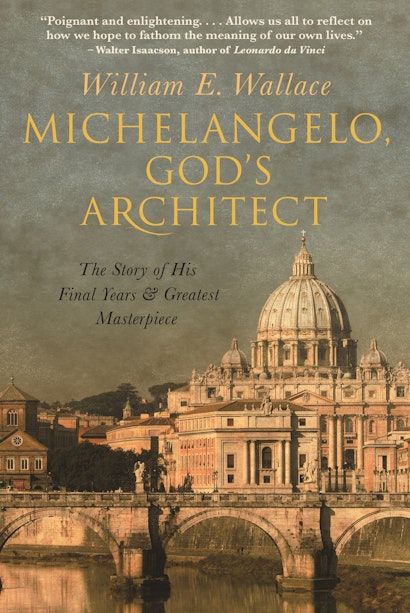

At that moment Pope Paul III ordered Michelangelo to take over the building of St. Peter’s Basilica. The artist protested his advanced age, the miserable condition of the “new” church which, although it had been under construction for 40 years, looked more like a Roman ruin than a Christian church. And he protested that “architecture isn’t my profession.” But one does not say “no” to a Pope. Thus, the artist who had carved the Pietà, the David, and Moses, and painted the Sistine Chapel became the supreme architect of the largest and most important building project in the world.

For the next seventeen years, from ages 71 to shortly before he died at 89, Michelangelo devoted himself to St. Peter’s. It gave him new purpose, and he came to believe that he was “put there by God to save St. Peter’s.” He was God’s architect.

Every day the octogenarian rode his horse to the worksite, conferred with his foremen, designed better ways to build, and solved engineering problems that had confounded his predecessors.

At St. Peter’s, Michelangelo was an architect and designer, but he was also the engineer, project and business manager, CEO, entrepreneur, and chief public relations officer. Re-organizing the chaotic worksite fell on Michelangelo’s aging shoulders. His daily concerns as the octogenarian overseer of the largest construction site in Christendom entailed, among other things, procuring stone, wood for scaffold, tools for carvers, an immense quantity of rope, organizing delivery of stone and water, building lime kilns and designing hoists. He personally hired the skilled foremen, designed templates for carvers, oversaw the lifting of stone blocks some 200 feet to construct the 18 buttresses and 36 columns that would support the majestic central dome.

As supervising architect, Michelangelo was responsible for everything, from design to construction, from the project overseers to the lowliest day laborer. And mostly, he worried about time. Would the pope live long enough, would Michelangelo live long enough to ensure that his design would be implemented?

For half a year in Rome, I looked from an apartment window on the dome of St. Peter’s, the dome that Michelangelo designed but never actually saw completed. The fact that the artist remained committed to building this crowning feature of St. Peter’s—in his 70s and 80s—with no hope of seeing the final result, made writing a book about it seem simple by comparison.

Michelangelo was in charge of just about 12 percent of the building’s 120-year long construction history. Given that he did not control some 88 percent of that history, it is astonishing that he accomplished as much as he did, and that we give him credit for the church. Others helped to complete the building, but it is Michelangelo’s design and his masterpiece.

I am just 67. I doubt that I will build a St. Peter’s, or even hear from the Pope. But, I also am not thinking of retiring, because our 70s and 80s may just be, like Michelangelo’s, the busiest and most creative of our lives.

William E. Wallace is the Barbara Murphy Bryant Distinguished Professor of Art History at Washington University in St. Louis. His books include Discovering Michelangelo: The Art Lover’s Guide to Understanding Michelangelo’s Masterpieces; Michelangelo: The Artist, the Man, and His Times; and Michelangelo at San Lorenzo.