International Macroeconomics presents a rigorous and theoretically elegant treatment of real-world international macroeconomic problems, incorporating the latest economic research while maintaining a microfounded, optimizing, and dynamic general equilibrium approach. This one-of-a-kind textbook introduces a basic model and applies it to fundamental questions in international economics, including the determinants of the current account in small and large economies, processes of adjustment to shocks, the determinants of the real exchange rate, the role of fixed and flexible exchange rates in models with nominal rigidities, and interactions between monetary and fiscal policy. The book confronts theoretical predictions using actual data, highlighting both the power and limits of given theories and encouraging critical thinking.

- Provides a rigorous and elegant treatment of fundamental questions in international macroeconomics

- Brings undergraduate and master’s instruction in line with modern economic research

- Follows a microfounded, optimizing, and dynamic general equilibrium approach

- Addresses fundamental questions in international economics, such as the role of capital controls in the presence of financial frictions and balance-of-payments crises

- Uses real-world data to test the predictions of theoretical models

- Features a wealth of exercises at the end of each chapter that challenge students to hone their theoretical skills and scrutinize the empirical relevance of models

- Accompanied by a website with lecture slides for every chapter

Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé is professor of economics at Columbia University. Martín Uribe is professor of economics at Columbia and the coauthor (with Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé) of Open Economy Macroeconomics (Princeton). Michael Woodford is the John Bates Clark Professor of Political Economy at Columbia and the author of Interest and Prices: Foundations of a Theory of Monetary Policy (Princeton).

- Preface

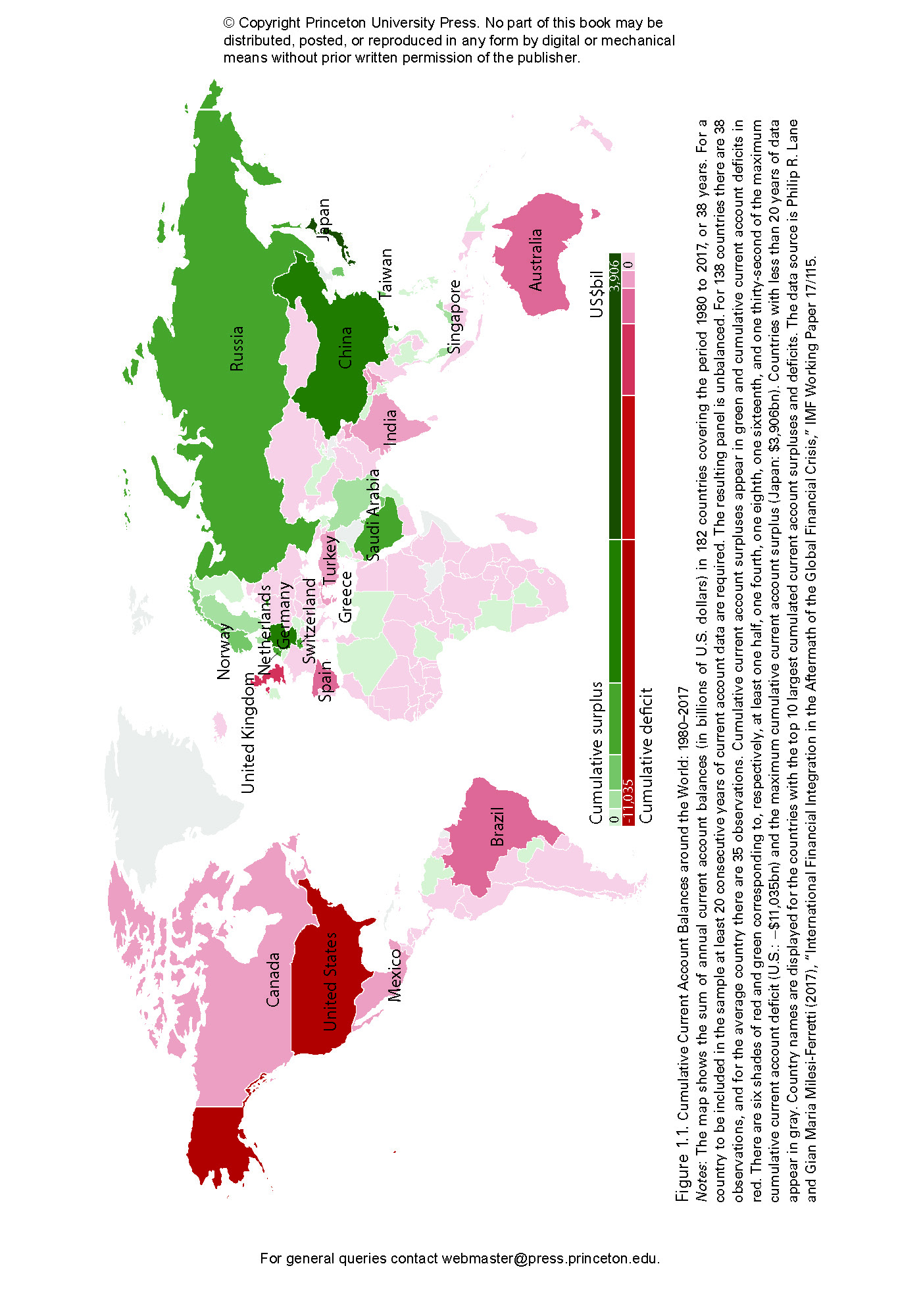

- CHAPTER 1 Global Imbalances

- 1.1 The Balance of Payments

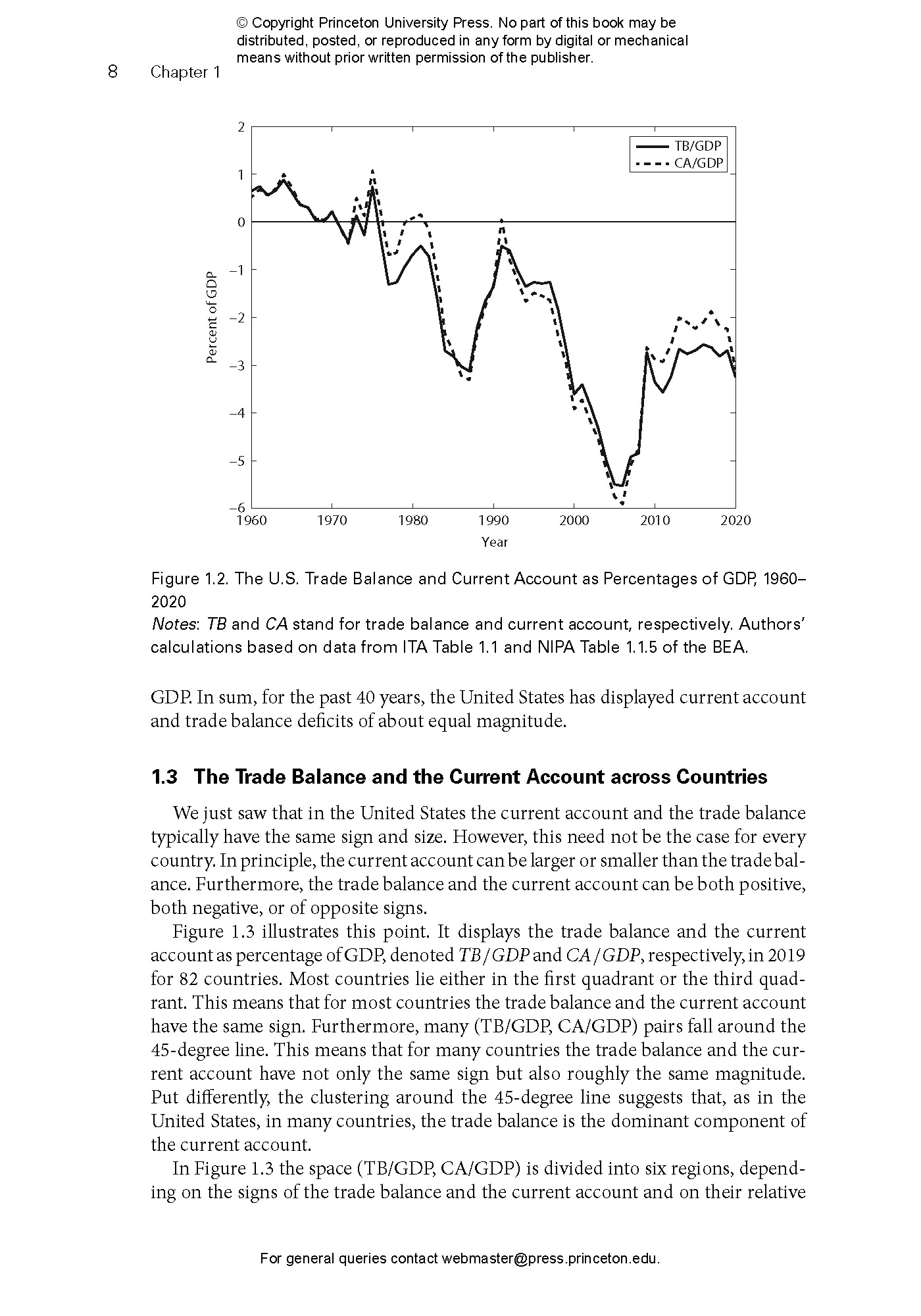

- 1.2 The Trade Balance and the Current Account

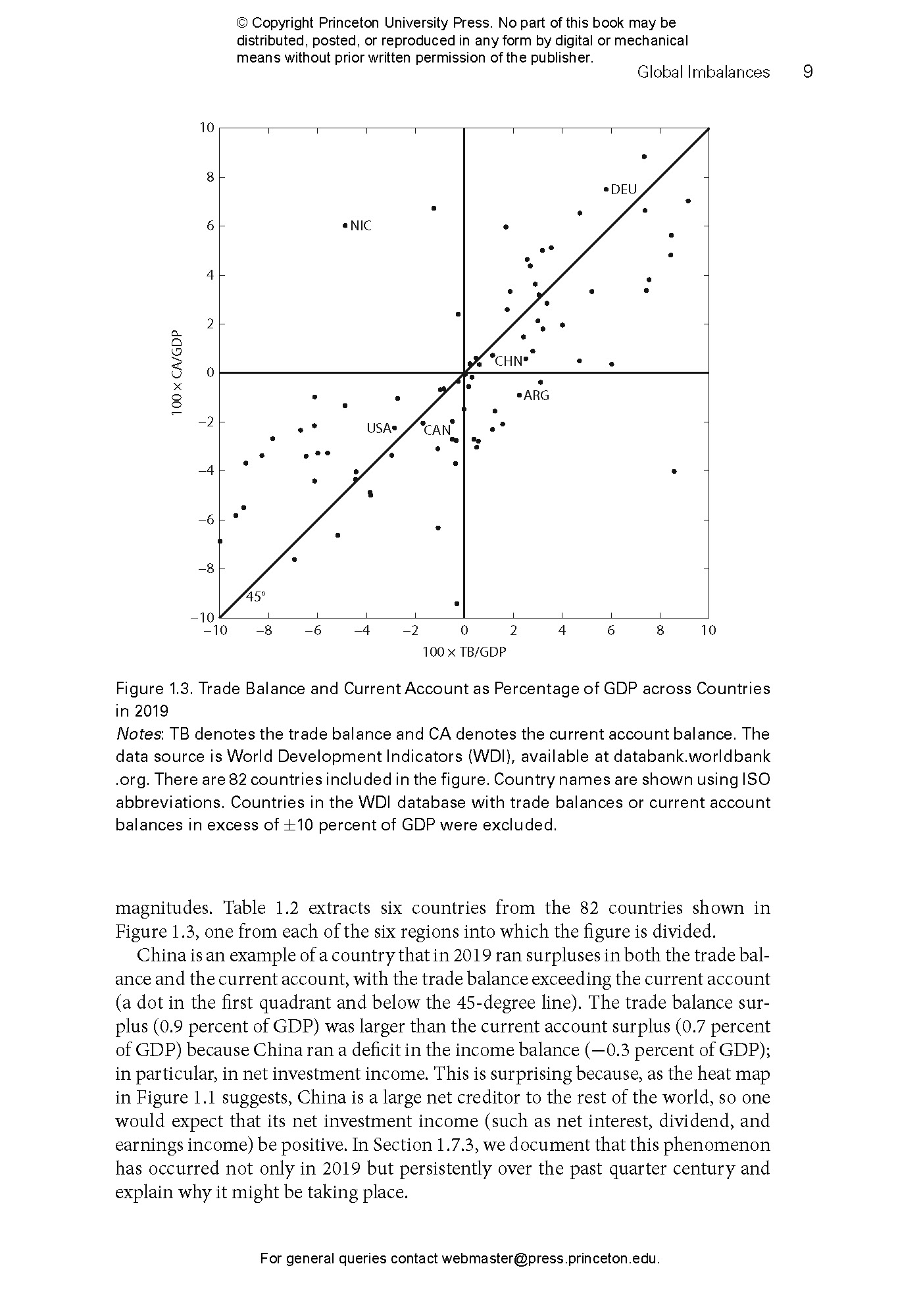

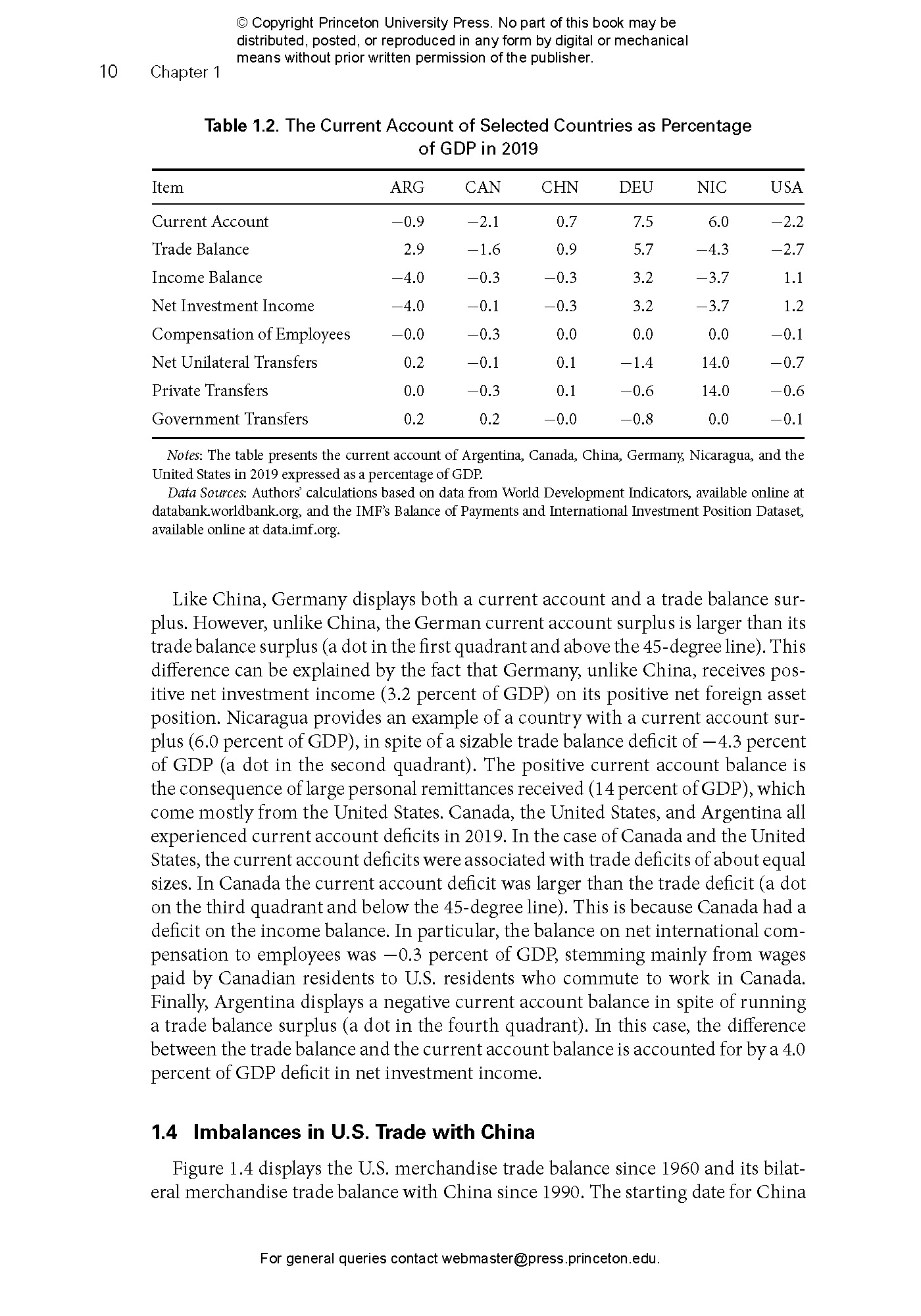

- 1.3 The Trade Balance and the Current Account across Countries

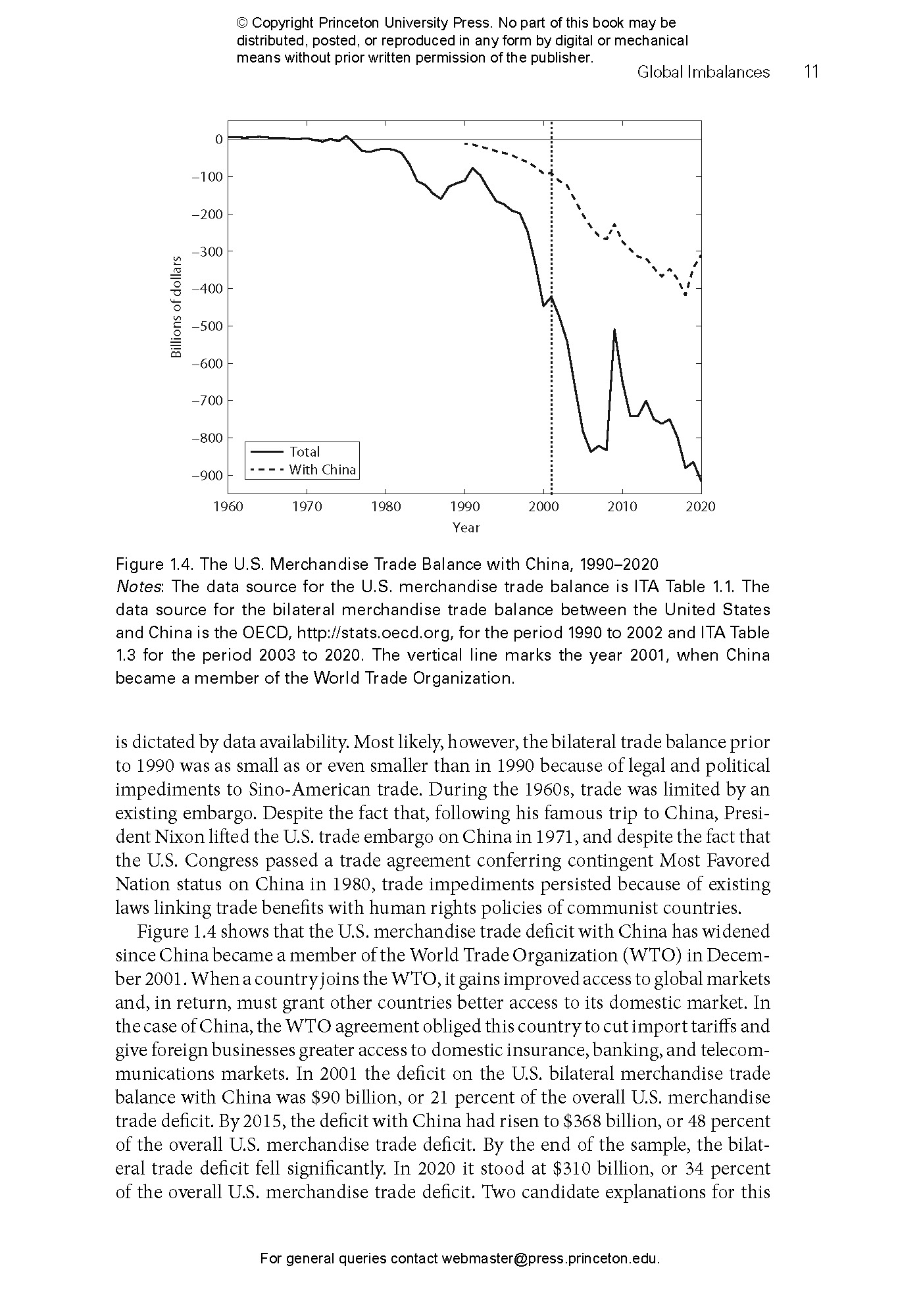

- 1.4 Imbalances in U.S. Trade with China

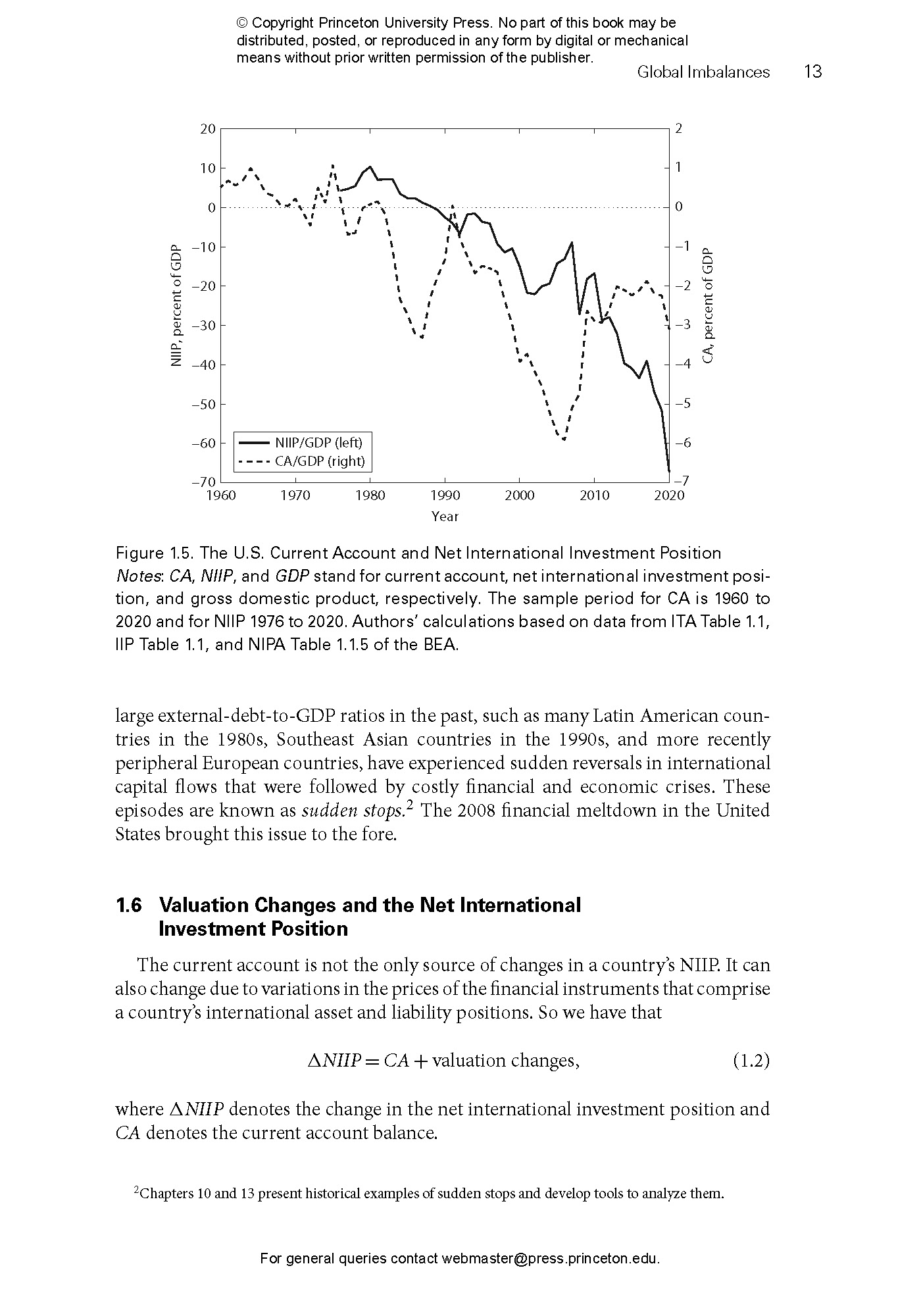

- 1.5 The Current Account and the Net International Investment Position

- 1.6 Valuation Changes and the Net International Investment Position

- 1.6.1 Examples of Valuation Changes

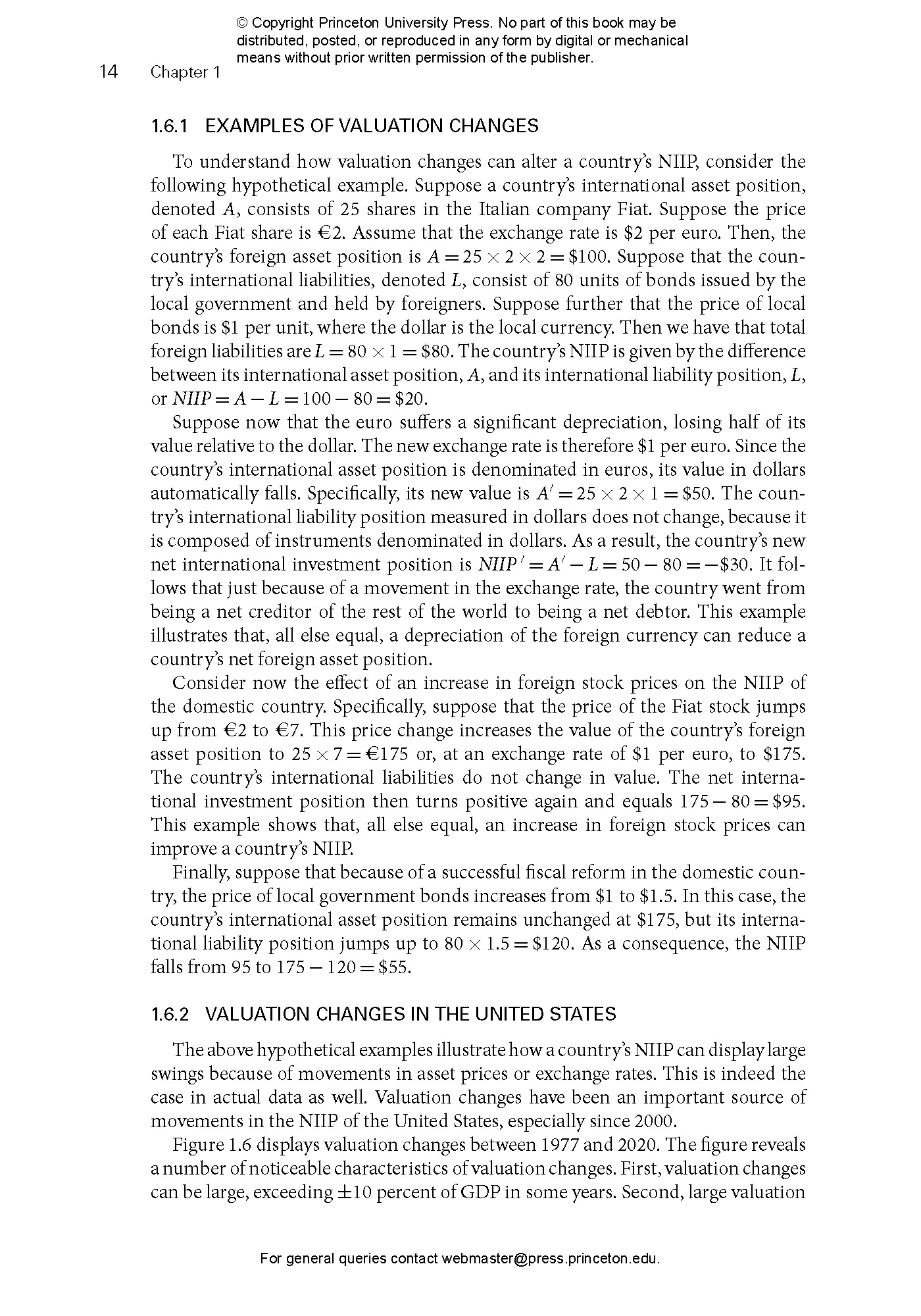

- 1.6.2 Valuation Changes in the United States

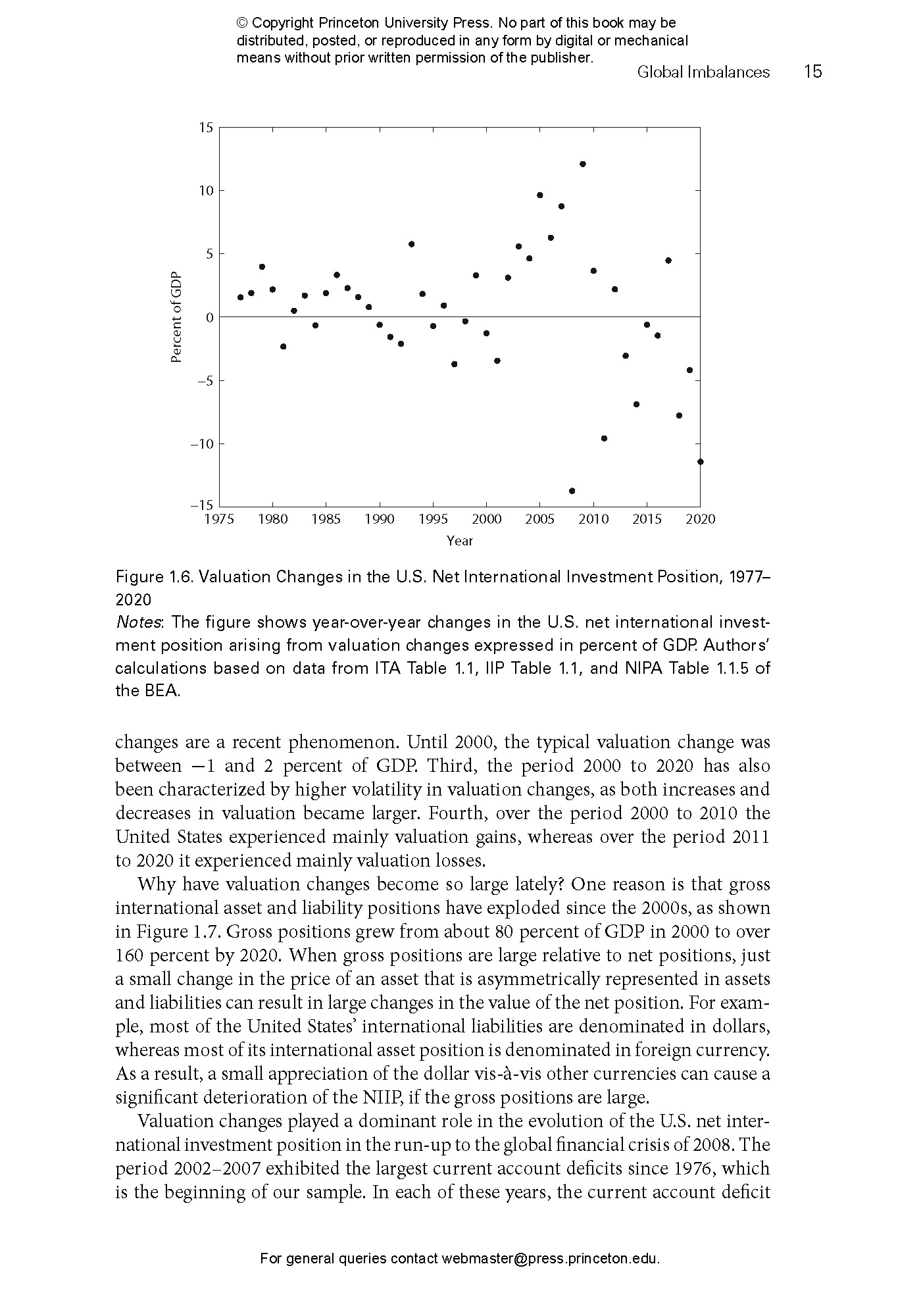

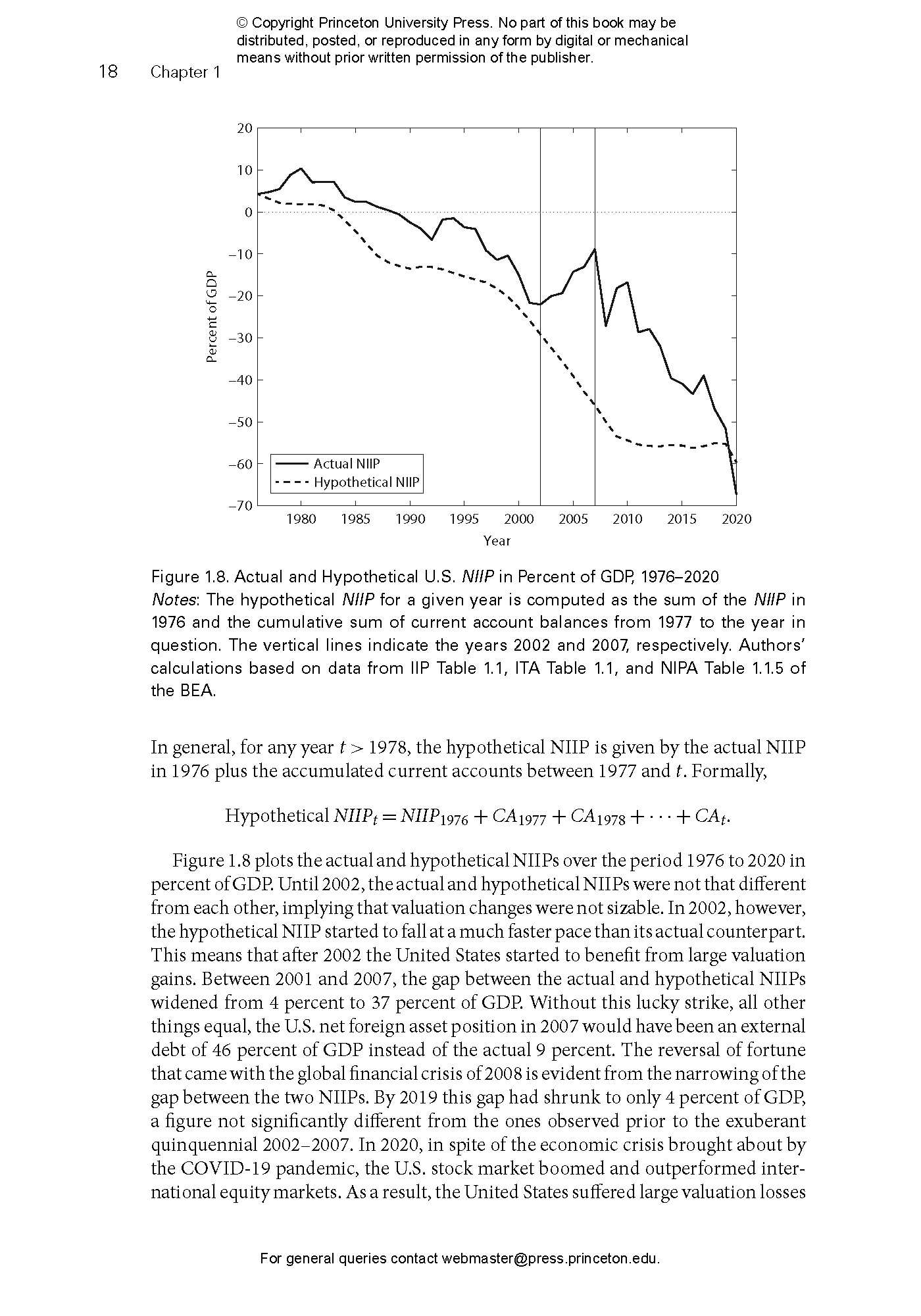

- 1.6.3 A Hypothetical NIIP That Excludes Valuation Changes

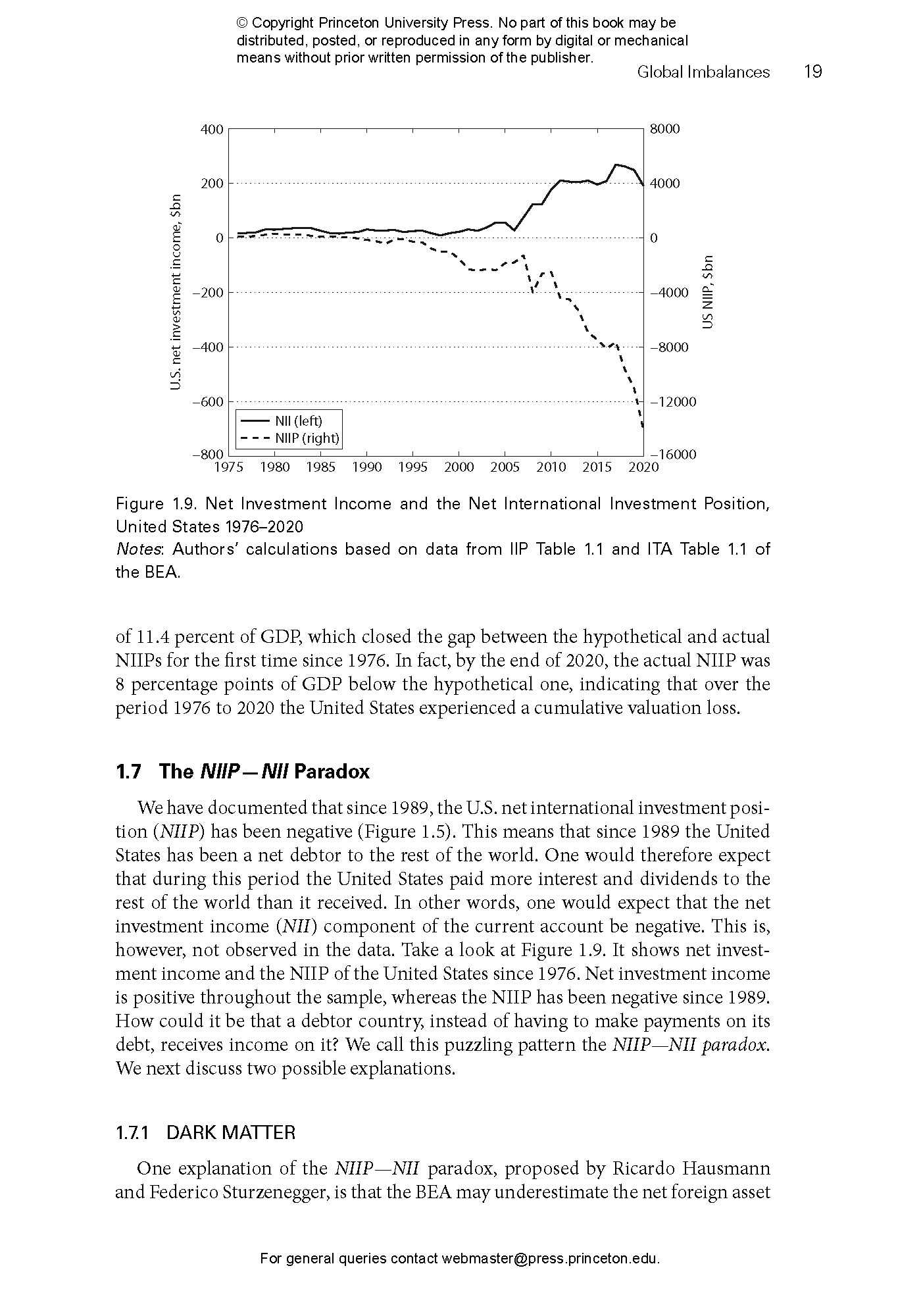

- 1.7 The NIIP—NIIParadox

- 1.7.1 Dark Matter

- 1.7.2 Return Differentials

- 1.7.3 The Flip Side of the NIIP—NII Paradox

- 1.8 Summing Up

- 1.9 Exercisessection.1.9

- PART I Determinants of the Current Account

- CHAPTER 2 Current Account Sustainability

- 2.1 Can a Country Run a Perpetual Trade Balance Deficit?

- 2.2 Can a Country Run a Perpetual Current Account Deficit?

- 2.3 Saving, Investment, and the Current Account

- 2.3.1 The Current Account as the Gap between Saving and Investment

- 2.3.2 The Current Account as the Gap between National Income and Domestic Absorption

- 2.4 Appendix: Perpetual Trade Balance and Current Account Deficits in Infinite Horizon Economies

- 2.5 Summing Up

- 2.6 Exercises

- CHAPTER 3 An Intertemporal Theory of the Current Account

- 3.1 The Intertemporal Budget Constraint

- 3.2 The Lifetime Utility Function

- 3.3 The Optimal Intertemporal Allocation of Consumption

- 3.4 The Interest Rate Parity Condition

- 3.5 Equilibrium in the Small Open Economy

- 3.6 The Trade Balance and the Current Account

- 3.7 Adjustment to Temporary and Permanent Output Shocks

- 3.7.1 Adjustment to Temporary Output Shocks

- 3.7.2 Adjustment to Permanent Output Shocks

- 3.8 Anticipated Income Shocks

- 3.9 An Economy with Logarithmic Preferences

- 3.10 Summing Up

- 3.11 Exercises

- CHAPTER 4 Terms of Trade, the World Interest Rate, Tariffs, and the Current Account

- 4.1 Terms of Trade Shocks

- 4.2 Terms of Trade Shocks and Imperfect Information

- 4.3 Imperfect Information, the Price of Copper, and the Chilean Current Account

- 4.4 World Interest Rate Shocks

- 4.5 Import Tariffs

- 4.5.1 A Temporary Increase in Import Tariffs

- 4.5.2 A Permanent Increase in Import Tariffs

- 4.5.3 An Anticipated Future Increase in Import Tariffs

- 4.6 Summing Up

- 4.7 Exercises

- CHAPTER 5 Current Account Determination in a Production Economy

- 5.1 The Investment Decision of Firms

- 5.2 The Investment Schedule

- 5.3 The Consumption-Saving Decision of Households

- 5.3.1 Effect of a Temporary Increase in Productivity on Consumption

- 5.3.2 Effect of an Anticipated Future Productivity Increase on Consumption

- 5.3.3 Effect of an Increase in the Interest Rate on Consumption

- 5.4 The Saving Schedule

- 5.5 The Current Account Schedule

- 5.6 Equilibrium in the Production Economy

- 5.6.1 Adjustment of the Current Account to Changes in the World Interest Rate

- 5.6.2 Adjustment of the Current Account to a Temporary Increase in Productivity

- 5.6.3 Adjustment of the Current Account to an Anticipated Future Productivity Increase

- 5.7 Equilibrium in the Production Economy: An Algebraic Approach

- 5.7.1 Adjustment to an Increase in the World Interest Rate

- 5.7.2 Adjustment to a Temporary Increase in Productivity

- 5.7.3 Adjustment to an Anticipated Future Increase in Productivity

- 5.8 The Terms of Trade in the Production Economy

- 5.9 An Application: Giant Oil Discoveries

- 5.10 Summing Up

- 5.11 Exercises

- CHAPTER 6 Uncertainty and the Current Account

- 6.1 The Great Moderation

- 6.2 Causes of the Great Moderation

- 6.3 The Great Moderation and the Emergence of Current Account Imbalances

- 6.4 An Open Economy with Uncertainty

- 6.5 Complete Asset Markets and the Current Account

- 6.5.1 State Contingent Claims

- 6.5.2 The Household’s Problem

- 6.5.3 Free Capital Mobility

- 6.5.4 Equilibrium in the Complete Asset Market Economy

- 6.6 Summing Up

- 6.7 Exercises

- CHAPTER 7 Large Open Economies

- 7.1 A Two-Country Economy

- 7.2 An Investment Surge in the United States

- 7.3 Microfoundations of the Two-Country Model

- 7.4 International Transmission of Country-Specific Shocks

- 7.5 Country Size and the International Transmission Mechanism

- 7.6 Explaining the U.S. Current Account Deficit: The Global Saving Glut Hypothesis

- 7.6.1 Two Competing Hypotheses

- 7.6.2 The Made in the U.S.A. Hypothesis Strikes Back

- 7.7 Summing Up

- 7.8 Exercises

- CHAPTER 8 The Twin Deficits: Fiscal Deficits and the Current Account

- 8.1 An Open Economy with a Government Sector

- 8.1.1 The Government

- 8.1.2 Firms

- 8.1.3 Households

- 8.2 Ricardian Equivalence

- 8.3 Government Spending and Twin Deficits

- 8.4 Failure of Ricardian Equivalence: Tax Cuts and Twin Deficits

- 8.4.1 Borrowing Constraints

- 8.4.2 Intergenerational Effects

- 8.4.3 Distortionary Taxation

- 8.5 The Optimality of Twin Deficits

- 8.6 Fiscal Policy in Economies with Imperfect Capital Mobility

- 8.7 Fiscal Policy in a Large Open Economy

- 8.8 Summing Up

- 8.9 Exercises

- PART II The Real Exchange Rate

- CHAPTER 9 The Real Exchange Rate and Purchasing Power Parity

- 9.1 The Law of One Price

- 9.2 Purchasing Power Parity

- 9.3 PPP Exchange Rates

- 9.3.1 Big Mac PPP Exchange Rates

- 9.3.2 PPP Exchange Rates for Baskets of Goods

- 9.3.3 PPP Exchange Rates and Standard of Living Comparisons

- 9.3.4 Rich Countries Are More Expensive Than Poor Countries

- 9.4 Relative Purchasing Power Parity

- 9.4.1 Does Relative PPP Hold in the Long Run?

- 9.4.2 Does Relative PPP Hold in the Short Run?

- 9.5 How Wide Is the Border?

- 9.6 Nontradable Goods and Deviations from Purchasing Power Parity

- 9.7 Trade Barriers and Real Exchange Rates

- 9.8 Home Bias and the Real Exchange Rate

- 9.9 Price Indices and Standards of Living

- 9.9.1 Microfoundations of the Price Level

- 9.9.2 The Price Level, Income, and Welfare

- 9.10 Summing Up

- 9.11 Exercises

- CHAPTER 10 Determinants of the Real Exchange Rate

- 10.1 The TNT Model

- 10.1.1 Households

- 10.1.2 Equilibrium

- 10.1.3 Adjustment of the Relative Price of Nontradables to Interest Rate and Endowment Shocks

- 10.2 From the Relative Price of Nontradables to the Real Exchange Rate

- 10.3 The Terms of Trade and the Real Exchange Rate

- 10.4 Sudden Stops

- 10.4.1 A Sudden Stop through the Lens of the TNT Model

- 10.4.2 The Argentine Sudden Stop of 2001

- 10.4.3 The Icelandic Sudden Stop of 2008

- 10.5 The TNT Model with Sectoral Production

- 10.5.1 The Production Possibility Frontier

- 10.5.2 The PPF and the Real Exchange Rate

- 10.5.3 The Income Expansion Path

- 10.5.4 Partial Equilibrium

- 10.5.5 General Equilibrium

- 10.5.6 Sudden Stops and Sectoral Reallocations

- 10.6 Productivity Differentials and Real Exchange Rates: The Balassa-Samuelson Model

- 10.7 Summing Up

- 10.8 Exercises

- PART III International Capital Mobility

- CHAPTER 11 International Capital Market Integration

- 11.1 Covered Interest Rate Parity

- 11.2 Covered Interest Rate Differentials in China: 1998–2021

- 11.3 Capital Controls and Interest Rate Differentials: Brazil 2009–2012

- 11.4 Empirical Evidence on Covered Interest Rate Differentials: A Long-Run Perspective

- 11.5 Empirical Evidence on Offshore-Onshore Interest Rate Differentials

- 11.6 Uncovered Interest Rate Parity

- 11.6.1 Asset Pricing in an Open Economy

- 11.6.2 CIP as an Equilibrium Condition

- 11.6.3 Is UIP an Equilibrium Condition?

- 11.6.4 Carry Trade as a Test of UIP

- 11.6.5 The Forward Premium Puzzle

- 11.7 Real Interest Rate Parity

- 11.8 Saving-Investment Correlations

- 11.9 Summing Up

- 11.10 Exercises

- CHAPTER 12 Capital Controls

- 12.1 Capital Controls and Interest Rate Differentials

- 12.2 Macroeconomic Effects of Capital Controls

- 12.2.1 Effects of Capital Controls on Consumption, Savings, and the Current Account

- 12.2.2 Effects of Capital Controls on Investment

- 12.2.3 Welfare Consequences of Capital Controls

- 12.3 Quantitative Restrictions on Capital Flows

- 12.4 Borrowing Externalities and Optimal Capital Controls

- 12.4.1 An Economy with a Debt-Elastic Interest Rate

- 12.4.2 Competitive Equilibrium without Government Intervention

- 12.4.3 The Efficient Allocation

- 12.4.4 Optimal Capital Control Policy

- 12.5 Capital Mobility in a Large Economy

- 12.6 Graphical Analysis of Equilibrium under Free Capital Mobility in a Large Economy

- 12.7 Optimal Capital Controls in a Large Economy

- 12.8 Graphical Analysis of Optimal Capital Controls in a Large Economy

- 12.9 Retaliation

- 12.10 Empirical Evidence on Capital Controls around the World

- 12.11 Summing Up

- 12.12 Exercises

- PART IV Monetary Policy and Exchange Rates

- CHAPTER 13 Nominal Rigidity, Exchange Rate Policy, and Unemployment

- 13.1 The TNT-DNWR Model

- 13.1.1 The Supply Schedule

- 13.1.2 The Demand Schedule

- 13.1.3 The Labor Market Slackness Condition

- 13.1.4 Equilibrium in the TNT-DNWR Model

- 13.2 Adjustment to Shocks with a Fixed Exchange Rate

- 13.2.1 An Increase in the World Interest Rate

- 13.2.2 Asymmetric Adjustment: A Decrease in the World Interest Rate

- 13.2.3 Output and Terms of Trade Shocks

- 13.2.4 Volatility and Average Unemployment

- 13.3 Adjustment to Shocks with a Floating Exchange Rate

- 13.3.1 Adjustment to External Shocks

- 13.3.2 Supply Shocks, the Inflation-Unemployment Trade-off, and Stagflation

- 13.4 A Numerical Example: A World Interest Rate Hike

- 13.4.1 The Pre-Shock Equilibrium

- 13.4.2 Adjustment with a Fixed Exchange Rate

- 13.4.3 Adjustment with a Floating Exchange Rate

- 13.4.4 The Welfare Cost of a Currency Peg

- 13.5 The Monetary Policy Trilemma

- 13.6 Exchange Rate Overshooting

- 13.7 Empirical Evidence on Downward Nominal Wage Rigidity

- 13.7.1 Evidence from U.S. Micro Data

- 13.7.2 Evidence from the Great Depression

- 13.7.3 Evidence from Emerging Countries

- 13.8 Appendix

- 13.9 Summing Up

- 13.10 Exercises

- CHAPTER 14 Managing Currency Pegs

- 14.1 A Boom-Bust Cycle in the TNT-DNWR Model

- 14.2 The Currency Peg Externality

- 14.3 Managing a Currency Peg

- 14.3.1 Macroprudential Capital Control Policy

- 14.3.2 Fiscal Devaluations

- 14.3.3 Higher Inflation in a Monetary Union

- 14.4 The Boom-Bust Cycle in Peripheral Europe, 2000–2011

- 14.5 Summing Up

- 14.6 Exercises

- CHAPTER 15 Inflationary Finance and Balance of Payments Crises

- 15.1 The Quantity Theory of Money

- 15.1.1 A Flexible Exchange Rate Regime

- 15.1.2 A Fixed Exchange Rate Regime

- 15.2 A Monetary Economy with a Government Sector

- 15.2.1 An Interest-Elastic Demand for Money

- 15.2.2 Purchasing Power Parity

- 15.2.3 The Interest Parity Condition

- 15.2.4 The Government Budget Constraint

- 15.3 Fiscal Deficits and the Sustainability of Currency Pegs

- 15.4 Fiscal Consequences of a Devaluation

- 15.5 A Constant Money Growth Rate Regime

- 15.6 Fiscal Consequences of Money Creation

- 15.6.1 The Inflation Tax

- 15.6.2 The Inflation Tax Laffer Curve

- 15.6.3 Inflationary Finance

- 15.7 Balance of Payments Crises

- 15.8 Appendix: A Dynamic Optimizing Model of the Demand for Money

- 15.9 Summing Up

- 15.10 Exercises