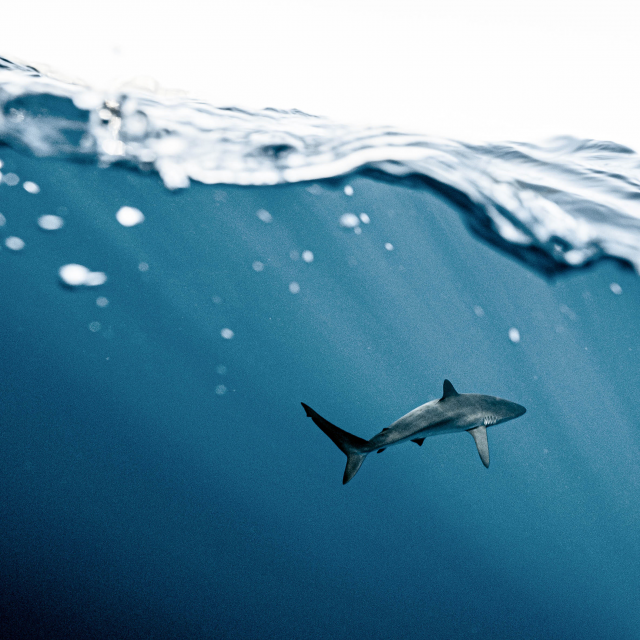

My first experience of a shark, as a small child, was uncomfortably close up. The shark was rolled up inside a sausage of netting, rather like Tom Kitten in the Tale of Samuel Whiskers (Potter, 1926—I will feel inadequate if I don’t include a literary reference somewhere). My father had rowed out the previous night to set our small fishing net for whiting, mullet and mackerel, and took me with him the next morning to retrieve breakfast. That memorable morning, however, the entire net was wrapped around a shark. It was impossible to untangle it at sea, so he heaved it on board our very small pulling dinghy. I have an indelible memory of slowly moving jaws and sharp teeth just a couple of inches away from my small bare toes. As we unrolled the net on the beach, my father identified a Tope Shark. We were both very upset that it could not be returned to the sea alive.

I never doubted my father’s infallibility but was disappointed not to find Tope in my Pocket Guide to the Sea Shore. I was already firmly hooked on the joys of collecting unfortunate specimens of marine life to identify and spent many happy hours during summer holidays on the Isle of Wight searching (generally unsuccessfully) for rarities spotted in my Pocket Guide. The nadir of my collecting obsession around that time might have been the repercussions of collecting over 200 live hermit crabs (several species) during a particularly low spring tide one evening. I lugged the large bucket up the hill to show off my catch, forgetting that my parents were at the Yacht Club Ball. Not wanting them to miss the final count, I put the crabs in the bath. The cottage became extremely noisy when my mother discovered them during the early hours next morning.

I was lucky to grow up in a house full of books, including lots of identification guides. I still have many of these originals, including some of my ‘seaside’ grandmother’s shell guides. Born in the year of Queen Victoria’s Golden Jubilee, she was a keen shell collector and travelled the world on her quest (in those days, by passenger ship). She gained a deservedly bad reputation when she and her friends disembarked in a new port for jumping into the front passenger seat to whisper into the taxi driver’s ear. Her companions would be unamused when their hijacked cab bypassed the handicraft market and went straight to the rubbish tip closest to the fishing harbour so that she could scamper over the stinking refuse in search of new specimens. Her huge shell collection was eventually donated to a regional museum—but I kept her books.

With that background, of course I studied marine zoology at University, discovered the joys of dichotomous identification keys (see below), and took up a career in marine conservation. For various reasons, I ended up in shark conservation. My ‘first shark’, Tope, is still among my favourite species. I own many shark books, including my original, very battered, copies of the two-part, monochrome, catchily-named, FAO Species Catalogue, Volume 4. Sharks of the World: An annotated and illustrated catalogue of shark species known to date. The last three words highlight the rapid rate with which new shark species were (and still are) being discovered and named. When published in 1984, the Catalogue included 342 species. In 1996, I eagerly opened its pages to work through the dichotomous key and identify the first shark I purchased from a stall at a small fish landing site in Sabah, Malaysia.

This was day one of an 18-month project funded by the UK government Darwin Initiative, studying elasmobranch (shark and ray) biodiversity in north-western Borneo. I could not key the shark out. I was in despair—I was clearly incompetent, and the project doomed before it had begun. Two days later, Leonard Compagno, author of the FAO Catalogue, joined us. He peered briefly at the mystery shark and remarked laconically “Humph, new species.” This little houndshark was the first of several undescribed species collected during our project. It still amazes me that we were working in a region that has been the study area of some of the world’s first great ichthyologists since the 19th Century, but it was still possible to walk around a fish market and pick up sharks new to science, as well as many of those first described in the mid 1800s. Astonishingly, nearly 40% of the world’s sharks and their relatives (rays and chimaeras) have been described by scientists during the past 20 years. But how could casual visitors or local students identify the species they saw, not just in Borneo but anywhere in the world? The FAO Catalogue is not widely known or accessible (despite updated editions now being available online) and, in black and white, it cannot show the extraordinary range of colours and patterns that characterise many shark species.

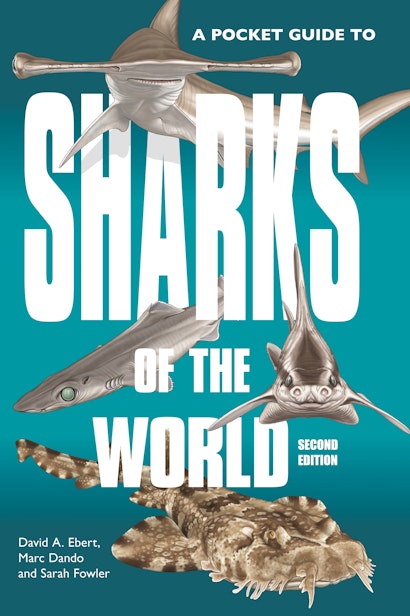

Sharks of the World was the brainchild of prolific marine illustrator Marc Dando, who first approached me to suggest that we produce a fully illustrated colour guide for all shark species. This was some way out of my comfort zone, but definitely possible in partnership with a world-famous shark taxonomist. Our 2005 guide, in partnership with Leonard Compagno, included about 400 named species, and 50 more unnamed—including some from Sabah. Eight years later, Leonard’s former student, David Ebert (aka ‘Lost Sharks Guy’) had joined the team and our 2013 book presented 501 species, 90 of which had been unnamed in 2005. The 2021 edition includes 536 species, 43 described since 2013.

Naturally, these guides have a dichotomous key. Many identification guides require readers to identify species from a combination of detailed illustrations and text. This can be difficult, particularly when many sharks, at first glance, look rather similar. Dichotomous keys present a series of choices that lead the reader to the correct identification. Our key identifies sharks to Order and Family level and directs readers to the relevant plates and species descriptions for these groups. We also explain how to take the precise measurements and photographs necessary for an expert to confirm the species’ identification, provide a key to detached shark fins, and illustrate jaws and teeth. The size of the main book (~600 pages) makes it unwieldy in the field, which is why there is also a pocket guide that can be taken anywhere.

These guides are not just a labour of love, but essential because shark conservation and management depends upon the accurate identification of whole sharks and their high-value products. For example, the teeth and jaws of protected species, such as White Shark, are still sold illegally. Shark fins are traded in huge quantities, to meet demand for shark fin soup. The fins of an estimated 73 million sharks used to enter international trade annually, before shark finning bans limited supply by outlawing the removal of fins and discard of shark carcasses at sea, and public education campaigns reduced demand. We hope that our books will support the implementation of these and other conservation measures, as well as encouraging more people to become involved in field studies of sharks—in the sea and onshore; at fish landing sites and in fish markets; in armchairs, libraries and classrooms. Furthermore, because knowledge of shark biodiversity and biology is still sparse in many parts of the world, those who use this book in the field might uncover new information, or even completely new shark species. We all still have a lot to learn about these fascinating animals, which are sadly more seriously threatened with extinction and in greater need of conservation and management action than any other higher taxon of vertebrate animals. Our aim is to spread our enthusiasm for sharks and encourage readers to improve their future chances of survival by supporting national and international efforts to end over-exploitation in fisheries and allow populations to recover.

Sarah Fowler is cofounder of the Shark Trust and the European Elasmobranch Association and a member of the IUCN Shark Specialist Group.